See how three different gear philosophies—powered by crunchy combos, classic guitars, piles of pedals, studio outboard gear, and a Beatles DI console fuzz—work together to bridge the band’s brash, punkified roots with their polished pop hooks.

Cage the Elephant was formed nearly 20 years ago in Bowling Green by vocalist Matt Shultz, guitarists Brad Shultz and Lincoln Parish, drummer Jared Champion, and bassist Daniel Tichenor. That core lineup has only changed once, with Nick Bockrath replacing Parish onstage in 2013 and officially in 2017. CTE’s earliest albums—2008’s Cage the Elephant and 2011’s Thank You, Happy Birthday—captured their punk-rock pandemonium that turned venues into hurricanes. Cage’s mayhem cloaked melodies, like a Trojan horse creating early-career earworms and sing-alongs out of hits “In One Ear,” “Ain't No Rest for the Wicked,” “Shake Me Down,” and “Aberdeen.”

2013’s Melophobia brandished a trio of mellower, melodious singles: “Come A Little Closer,” “Take It or Leave It,” and “Cigarette Daydreams.” Then, 2015’s Tell Me I’m Pretty saw the band enter Easy Eye Sound to work with Dan Auerbach, sending the band’s sonics back to the ’60s with an emphasis on direct, pointed performances and console-driven fuzz. Their last two albums, 2019’s Social Cues and 2024’s Neon Pill, partnered them with producer John Hill, who helped wrap their memorable hooks in a smokier, after-hours backdrop that incorporated ’80s sheen with drum machines, shifting synth textures, and sleek production that pulses with flow and emotion.

The constant glue that holds these albums together (aside from the members' cohesive creativity) is the constant application—in varied amounts—of garage rock, psychedelia, and a little bit of danger. Even their softest, smoothest work portrays these gripping vibes. And while the velvet packaging of their songs have them sounding more Abbey Road than Albini—earning the group back-to-back Grammys for Best Rock Album for Tell Me I’m Pretty and Social Cues—the Shultz brothers still bring their signature piss-and-vinegar performances to the stage, where the front row will likely play host to both throughout any given setlist.

Before the band’s Bonnaroo set on Saturday June 15, Cage the Elephant invited PG’s video team to their rehearsals inside East Nashville’s Steel Mill space to cover the gear they’d be touring with in support of their sixth album, Neon Pill. On guitar, lap steel, and pedal steel, Nick Bockrath starts off the Rundown going through his sizzling setup that includes custom guitars, a bountiful pedalboard, and a special instrument from a deceased friend and Nashville legend. Then, tech Mason Osman details how Brad Shultz transformed his rig to mimic his preferred recording setup that relies on studio tube preamps and compressors for a direct, broiling sound. Lastly, tech Bailey Griffith shows a simplified-but-tsunami-sounding bass setup that includes two Fender 4-strings and 300W tube heads that kick like a mule.

Brought to you by D’Addario

Some Like It Hot

Guitarist Nick Bockrath was approached by luthier Jacob Harper to collaborate on his “dream” guitar. The fellas landed on Harper’s existing Marilyn model with some key requests: a Bigsby vibrato, gold hardware, a Bockrath-drawn dude on the truss-rod cover, and the striking red-sparkle finish. Harper was the brains behind the pinball-flapper-button kill switch (with Bockrath’s blessing). The semi-hollow has a chimey, jangly tone thanks to its TV Jones Filter’Tron pickups. All the knobs were originally identical, but as Nick says, “we just keep it moving,” so he’s been replacing the road thrash with random knobs from his personal collection as needed. All his electrics take Ernie Ball Power Slinkys (.011–.048).

Sniped

Los Angeles-based producer John Hill, who worked with Cage the Elephant on Social Cues and their brand-new Neon Pill, had his eye on this early 1990s Gibson Les Paul Deluxe goldtop that was for sale at Carter’s Vintage Guitars. He sent the listing link to Nick Bockrath, who was going to visit the store to inspect the goldie. Bockrath called Hill from the shop, who wondered how the guitar sounded. Nick’s sly response: “It sounds like I’m gonna buy it in five minutes [laughs].” The previous owner removed the original pickups and dropped in a P-90 in the bridge and a gold-foil in the neck.

Torn and Frayed

Bockrath scooped this on a trade from Blues Vintage Guitars in Donelson. He can’t quite nail down its birth year, but from the serial number and similar online listings, he’s been able to deduce that it’s a SG Custom from 1969–’71. This is a bus companion that travels with Nick because he doesn’t want it out of his sight.

Trust in Russ

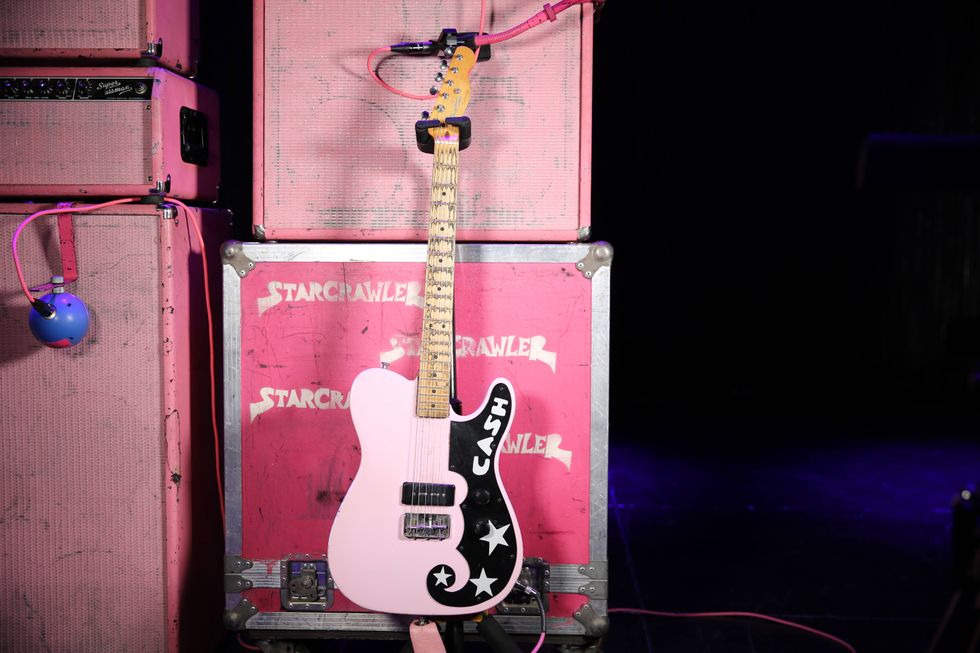

Russ Pahl is a pedal-steel guitar icon. He’s on a short list of first calls when an artist needs that classic country sound. On top of being an ace musician, Pahl builds partscaster guitars, and he assembled this mean T with Nick in mind. It has a standard T-style bridge pickup, but to give Bockrath a bit more bite, he opted for a Firebird-style mini humbucker for the neck slot.

Knockin' on Heaven's Door

Nick’s early Nashville mentor and a friend’s father William "Bucky" Baxter played lap- and pedal-steel guitar for Bob Dylan and Steve Earle. This century-old Gibson BR-6 lap steel toured with both iconic songwriters. Bucky sold this to Bockrath because, he said, “if you were ever gonna play lap steel in a rock ’n’ roll band, this would be the one,” so Nick honors his old pal every night.

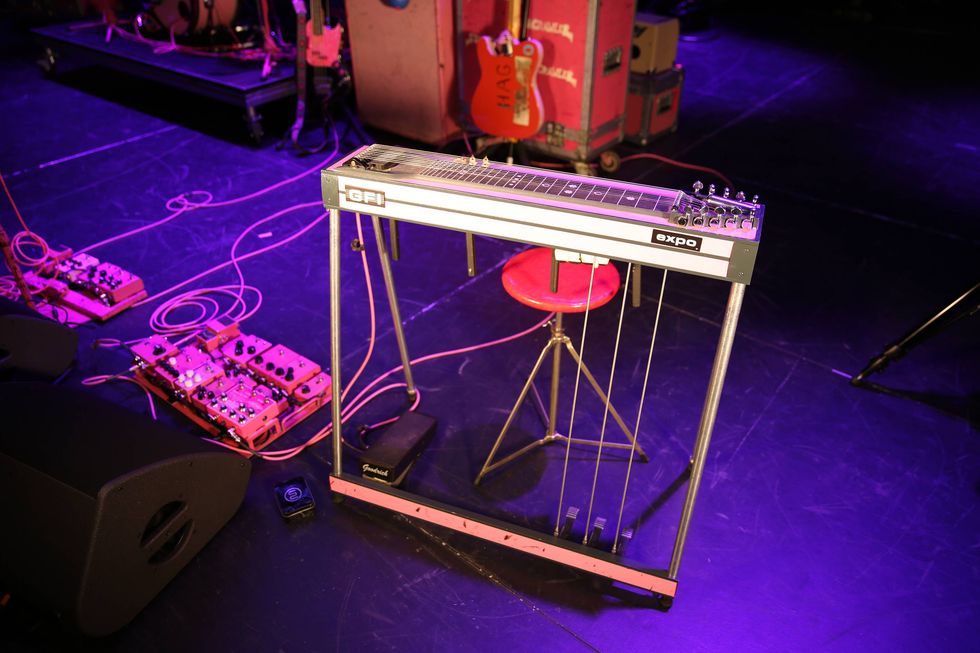

Steeler

Bucky Baxter got Bockrath hip to the GFI pedal-steel guitars when he first expressed interest in the slide instrument. Nick landed on the single-neck GFI Ultra 10-string model that’s added fresh elements to Cage’s sound on their last two albums and subsequent tours.

Royale with Cheese

Bockrath runs a stereo setup with a two-amp attack that includes a pair of Supro 1933 Royale 2x12 combos. He digs them for being excellent at taking pedals, having modern features like tube-buffered effects loops and variable power settings, and their natural, responsive overdrive.

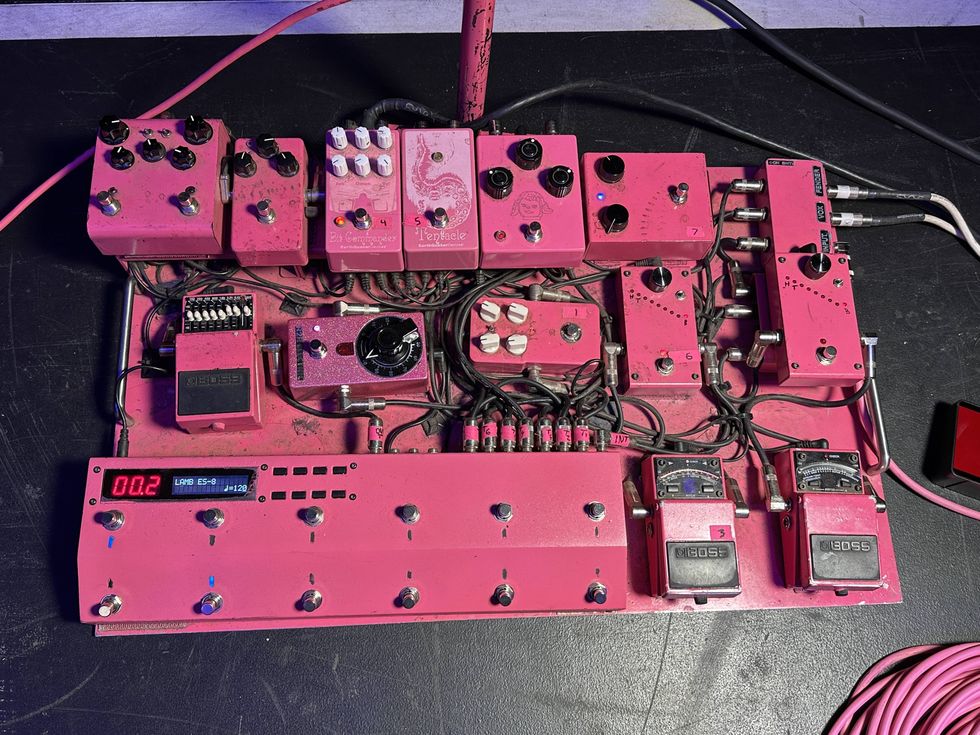

Nick Bockrath's Pedalboard

Bockrath has everything but the kitchen sink on his stomp station, but he assured us that each pedal has its role and it’s all very organized. Starting on the left there are four separate time machines—a duo of Boss DD-8 Digital Delays, EarthQuaker Devices Disaster Transport, and a Death By Audio Echo Dream 2. Modulation and weirdo effects include a Moog Moogerfooger MF-108M Cluster Flux, a Boss TR-2 Tremolo, an Electro-Harmonix Mel9, and a Malekko Omicron Vibrato. His pair of fuzzes are the single-knob Big Ear Pedals Betty White and the Malekko Diabolik. Reverb comes from the amps and the Malekko Spring Chicken, pitch-shifting is handled by the venerable DigiTech Whammy, and spicing up his signal is either an Analog Man Comprossor or a Pedal Projects Growly boost. All the pedals are routed through the GigRig G2, a Lehle 3at1 Instrument Switcher allows him to quickly bounce around his three string-bending roles, and a Boss TU-3S keeps his guitars in check.

Tuxedo

When we last spoke with Cage in 2014 and for most of the band’s earliest years, Brad Shultz destroyed and revived import Fender Mustangs. He preferred the short-scale studs for their thin, bright sound, compact frame, and their ability to handle several surgeries. Since working with Dan Auerbach and John Hill in the studio, Shultz has broadened his stable to include models from Gretsch, Kay, Gibson, and others depending on what the song needs. For the band’s summer tour, he’s slimmed down his options to three main instruments. First up is a Silvertone 1449 BSF that employs the company’s “lipstick” single-coils that offer Brad a similar bitey, high-end snarl he’s used to with the Mustangs. Both of Shultz’s electrics take Ernie Ball Power Slinkys (.011–.048) and he hits them with Dunlop Tortex .50 mm picks.

Spacely Space Sprockets

If his Silvertone 1449 is a blast from the past, this Baranik RE-1 is one of the most futuristic designs guitardom has seen in years. Luthier Mike Baranik specializes in refurbishing and repurposing recycled parts with a modern eye, while maintaining a strict focus on tone and playability. This RE-1 features his handwound gold-foil pickup that slides, in real time, to provide maximum sonic flexibility. Other interesting bits include a wood-intonated saddle, glow-in-the-dark fret markers, illuminated control pod, and a total weight of six pounds.

Bell Curve

A handful of songs during Cage shows will put Shultz on this Gibson J-45 Standard, including “Ain’t No Rest for the Wicked,” “Trouble,” and the title track off their newest album Neon Pill. To avoid any feedback or howling buzz, his tech Mason Osman slid in a D’Addario Screeching Halt Soundhole Plug. And this burst beauty takes Ernie Ball 2004 Earthwood 80/20 Bronze strings (.011–.052).

From the Studio to the Stage

We interviewed Brad around the Tell Me I’m Pretty sessions that were recorded with Dan Auerbach in his Nashville Easy Eye Studio, and that’s where the band first explored plugging straight into a console. “As a guitarist, the whole approach of going direct really appealed to me, and I got that from [’60s] bands. A lot of them did the exact same thing—went right into the console. But I think the thing that influenced us the most about those bands was the separation of their tracks. When you sit and really listen to their recordings, you notice how each instrument is doing something very specific. Each part is so thought-out and placed so deliberately. I really drew from that.”

That immediate connection between instrument and player resonated with Shultz so much that he revamped his live rig to include studio gear. He tours with no amps and no modelers; instead, he plugs his guitars into a pair of rack-mounted Thermionic Culture devices for his pure, lively tone—a Phoenix SB stereo valve compressor and The Rooster 2 preamp.

Back in 2016, Shultz explained that this synergy provides a different playing experience. “It feels more human. When I hear that, I really hear the person playing, not so much this amp sound. The strings speak for themselves, almost, if that makes any sense. You can hear the pick actually hitting each individual string as you strum a chord, or you can hear each individual stroke of a lead part. So that was really appealing to me, maybe because I'm such a raw player. I basically beat the shit out of a guitar. I'm very heavy-handed. I want to hear the separation between each string when I'm strumming a chord.”

Brad Shultz's Pedalboard

All his filth, fury, and ferociousness come from hitting the rack gear with as much input signal as possible. The incremental levels of destruction are handled by five agitators—a JHS Colour Box V1, a JHS Crayon, a JHS Colour Box V2, an EarthQuaker Devices Tone Job, and a Jext Telez White Pedal. The rest of his pedal roster contains a Boss DD-7 Digital Delay, MXR Phase 100, a pair of MXR Reverbs, Caroline Kilobyte lo-fi delay, and a Boss AW-3 Dynamic Wah. Shultz’s utility boxes are a Boss NS-2 Noise Suppressor, a couple of Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuners, a Radial Engineering BigShot ABY, and a Voodoo Labs PX-8 switcher simplifies all his changes.

Big Cat Growl

Original bassist Daniel Tichenor has been a Fender-heavy thumper. When we saw his rig in 2014, he was using a Jazz and P basses; when he spoke with PG about Tell Me I’m Pretty, he recorded with P, Jag, and Mustang 4-stringers. For this 2024 run supporting Neon Pill, he’s mainly laying down the groove with the above Fender American Standard Jaguar bass that uses La Bella RX-S4D Rx Stainless Roundwound Bass strings (.045–.105). Tichenor bounces back and forth between fingerstyle and using a pick, but when he does the latter, he rakes the strings with Dunlop Tortex .88 mm picks.

'Stang Stinger

For Cage’s mellower numbers, Tichenor will saddle up on this Fender Player Mustang bass that rides with La Bella 760FS Deep Talkin' Bass Flatwound strings (.045–.105).

Tower of Power

The Jag and ’Stang go through a Fender Super Bassman 300W head (the second is a backup) that feeds two Fender Bassman 810 Neo cabinets.

Daniel Tichenor's Pedalboard

The lone effect that colors Tich’s tone is a Fender Engager Boost that spurs the flatwound Mustang with a punch of dBs. The other boxes on the Pedaltrain Nano+ board are DIs for FOH, and the boost is powered with a Truetone 1 Spot Pro CS6.

Shop Cage the Elephant's Rig

Gibson Les Paul Deluxe Goldtop

Gibson Custom 1963 Les Paul SG Custom Reissue

Supro 1933R Royale 2x12 Combos

Boss DD-8 Digital Delay

EarthQuaker Devices Disaster Transport

Boss TR-2 Tremolo

Electro-Harmonix Mel9

Lehle 3at1 SGoS Instrument Switcher

Gibson J-45 Standard

JHS Colour Box V2 Preamp Pedal

EarthQuaker Devices Tone Job

MXR M107 Phase 100 Phaser Pedal

MXR Reverb

Boss AW-3 Dynamic Wah

Boss NS-2 Noise Suppressor

Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuner

Radial Engineering BigShot ABY

Voodoo Labs PX-8 Switcher

Fender Player Mustang Bass

Fender Engager Boost

Fender Super Bassman 300W Head

Fender Bassman 810 Neo Cabinet

Ernie Ball Power Slinkys (.011–.048)

Ernie Ball 2004 Earthwood 80/20 Bronze Strings (.011–.052)

La Bella RX-S4D Rx Stainless Roundwound Bass Strings (.045–.105)

La Bella 760FS Deep Talkin' Bass Flatwound Strings (.045–.105)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)