Eric Johnson knows that excessive pride gets in the way of true progress, and that having extraordinary talent doesn’t beget personality or, simply put, make you better than anyone else. “I’ve spent so long being involved in [playing music] that, at one point, you take a break and go, ‘Yeah, but that’s not me—that’s just something I do. Who am I?’” he shares. “Regardless of how well you do it and how appreciated you are, it’s not like a carte blanche calling card that gives you any kind of real entitlement in life. If you think it does, then you don’t know who you are.”

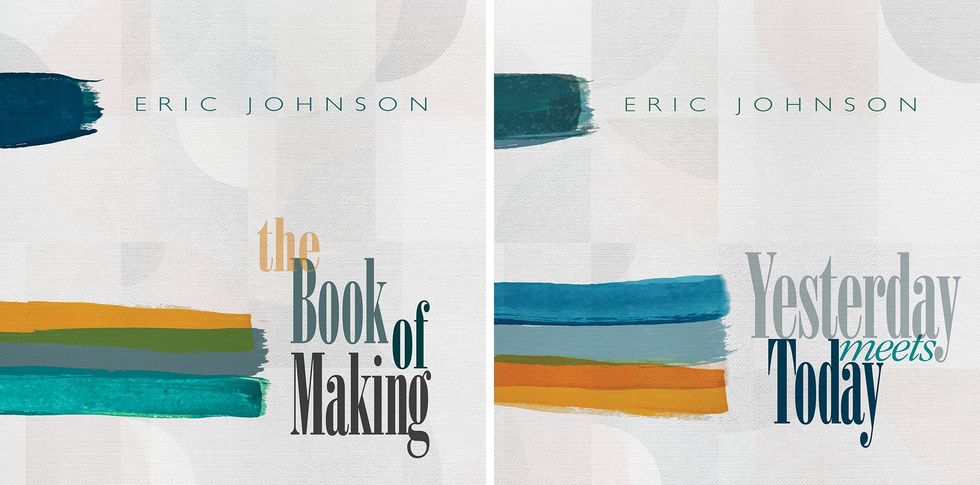

That philosophy, along with his passion for the instrument, has, over time, superseded any ego-inflating diversions that can come from fame. And rather than resting on his legacy, the guitarist is building on it with the release of two albums: The Book of Making and Yesterday Meets Today. The records came together in a process of creative reconnaissance, where Johnson dove into his vault of recordings to find forgotten song ideas that could be polished, fleshed out, and rejuvenated for release.

Eric Johnson - Soundtrack Life (Official Visualizer)

The 18 tracks that collectively make up both albums include those that fit into a classic Johnson style, such as the brightly textured lead single from The Book of Making, “Soundtrack Life,” along with ones that explore other territories, like that album’s gentle, piano-guided “To Be Alive,” co-written with singer/guitarist Arielle, and a cover of the blues classic “Sittin’ on Top of the World” by the Mississippi Sheiks (famously covered by Howlin’ Wolf). These new compositions range from panoramic instrumentals to lilting ballads, embroidered by the guitarist’s fluid, crystalline tone and uplifting vocals. And together, they offer a new look into Johnson’s characteristic finesse.

When the last few weeks of his tour got cancelled in March 2020, Johnson, amidst the societal standstill and isolated from his bandmates, decided that the best use of his time would be to revisit his old demos and musical sketches. As he navigated through the tiny snippets, little chord changes, and other bits and pieces, he discovered that he had far more material available than expected and set to arranging and recording.

“When I take the vantage point of a listener, it’s easier to tell if stuff really has merit.”

I felt, well, if I’m going to be isolated, let me go try to find something to work on,” he says. “There’s a handful of songs that were written from scratch, and towards the end of the period I brought musicians in and we recorded new stuff. Then there’s a couple of tracks that I didn’t do anything to. They were just left over from outtakes from other records. But predominantly it was just stuff that was barely started, and I did a whole lot of work on my own.”

The songs done from scratch include “Floating Through This World” and “To Be Alive” from The Book of Making and “Hold on to Love” and “JVZ” (dedicated to Johnson’s late tour manager and guitar tech, Jeff Van Zandt) from Yesterday Meets Today. The original idea for the former album’s “My Faith in You” dates back 20 years, although its oldest song is “Love Will Never Say Goodbye,” which was built from a rough mix on a 25-year-old cassette. “That’s all I had,” Johnson says. “I couldn’t find the master take. It had synthesizer, bass, drums, and a vocal that was a little too low in level, but I just went with it. Then I added several guitars to it, and background vocals and percussion.”

Johnson’s distinctive hybrid picking technique is partly derived from steel guitar players, leading him to pluck all the strings in a chord at once. He also favors picking near the end of the pickguard, to get a warm, round tone from single notes.

Photo by Ken Settle

Twenty-five years ago, Johnson was having an especially fertile creative period, despite his reputation as a painstaking studio craftsman. His albums Venus Isle and Seven Worlds sprang from that era, and his tenure on tour with fellow maestros Joe Satriani and Steve Vai was preserved on G3: Live in Concert. And while he’s more relaxed about record-making these days, he’s no less creative or prolific. The popular virtuoso says that every time he sets out to make an album, he usually ends up making two—and stashes the excess recordings in his vault. In this case, his efforts at rekindling his past inspirations resulted in 28 tracks that were pared down to the final 18, although he intends to eventually release five or six more of the original set on an upcoming EP.

Producer Kelly Donnelly, who has worked with Johnson on eight previous albums plus his 2014 collaboration with Mike Stern, Eclectic, helped with some of the engineering, but Johnson did most of it himself. In the process, he learned something interesting about the usefulness of low-fidelity recordings: If you pair them with recordings of a higher quality, the combination can create a compelling depth of field. This meant that he was able to salvage and build upon some of his more compromised cassette recordings. “I found that to be fascinating—it was like, ‘Wow, that kind of works.’ I didn’t know that was going to happen.”

“There has to be an element of the music that has enough power and velocity to reach out to the listener, rather than just be sonically nice to listen to.”

In 2020, Johnson worked with Fender to create a replica of his 1954 “Virginia” Stratocaster, which he played on many of the tracks from The Book of Making and Yesterday Meets Today. The guitar’s body is made with the less commonly seen sassafras wood and set up with a DiMarzio bridge pickup and ’57/’62 single-coil Strat middle and neck pickups. On the albums, he played a handful of other models, including a 1957 Strat with a maple neck, a 1965 Gibson ES-345 semi-hollowbody, and a late-’50s Les Paul. He also plays a National lap steel and Danelectro Vincent Bell Coral sitar on some tracks.

When it comes to songwriting, Johnson comments that his self-proclaimed perfectionist tendency to overthink things can work against him. “The songs where you’re really pushing and striving and stressing end up sounding like that,” he says, while the ones that just flow are the ones that are, for him, most worth working on. His creative process usually begins with making recordings of musical snapshots on his iPhone. He’ll capture a phrase on guitar or piano, or sometimes record himself singing a vocal or instrumental melody to later revisit. “They’re pretty embarrassing, if anybody ever found ’em,” he laughs, referring to the latter.

Eric Johnson’s Gear

Although Johnson records with a variety of guitars, his weapon of choice—even before he immortalized his own version of the model’s sound via 1986’s Tones and 1990’s Ah Via Musicom—has long been the Fender Stratocaster.

Photo by Jim Summaria

Guitars

- Eric Johnson Virginia Fender Stratocaster

- 1957 Fender Stratocaster

- 1965 Gibson ES-345

- 1950s Gibson Les Paul

- National lap steel

- Danelectro Vincent Bell Coral Sitar

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario EPN110 Pure Nickel sets

- Dunlop Jazz IIIs

Effects

- TC Electronic Stereo Chorus

- Electro-Harmonix Memory Man

- Vintage Echoplex (modded for use as preamp)

- ’60s Dallas-Arbiter Fuzz Face

- Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

- BK Butler Tube Driver

Amps

- Marshall plexi 50

- Two-Rock Classic Reverb

- Marshall 4x12

- Fender Bandmaster Reverb

- Electro-Voice speakers

Deciding which compositions to keep or toss can be a curious process. To better judge his own writing, Johnson says it’s important for him to detach and act like an audience member or listener—so not to give himself any favoritism. “You have to dispel all that,” he says. “When I take the vantage point of a listener, it’s easier to tell if stuff really has merit.” While that can sound like a purely imaginative exercise, he has a rather practical way of getting to that perspective. Often, he’ll just crank up his studio monitors and walk into another room to listen.

“That helps you tell whether something’s really reaching you or not,” he elaborates, “because you’re not sitting there enveloping yourself and hyping yourself on something. There has to be an element of the music that has enough power and velocity to reach out to the listener, rather than just be sonically nice to listen to.”

“There’s nobody who’s going to be able to do what you do the way you do it.”

Johnson calls the evolution of his sound a “crazy process” that he says could go on forever, but he tries to let the music speak and will work to rise to the occasion to come up with a part that fits. “Sometimes that means I have to study a part that I can’t normally play.” Which means his self-labeled “perennial student” mentality has its benefits.

When asked if he experiences self-doubt, Johnson shares that he believes the habit of comparing yourself to others can be demoralizing, but he looks to practicing gratitude as a solution. “It’s just trying to be thankful for what you have and not compare yourself to other people. The more you’re in yourself and do your best.… There’s nobody who’s going to be able to do what you do the way you do it.”

Some of the 18 songs spread over Johnson’s two new albums trace back 25 years, to the era of his first G3 Tour and his records Venus Isle and Seven Worlds.

Johnson was born into a musical family, with a father who was an enthusiastic music appreciator and three sisters who studied piano. His parents have said that he loved records when he was 3 years old. They listened to a lot of swing and showtunes, he says, which he developed a taste for as a child. He got his own record player when he was 5.

The guitarist walks through the lightshow clouds on the Experience Hendrix tour in 2014, searching for butterflies, moonbeams, and fairy tales within his alluring sound.

Photo by Frank White

When Johnson got into playing music, he began to study piano at age 11, then took some lessons on guitar—though on guitar, he was mainly transposing what he learned on piano. His passion for wood and strings, however, quickly took over. “I loved it so much that I incessantly worked at it to get better, and it’s all I wanted to do,” he says.

“When I was a kid and saw all the cats playin’ guitar—Cream and the Yardbirds and all those people—I was like, ‘This is awesome,’” he shares. “Plus, it was kind of the first generation of overdriven guitar with fuzz tones. It was a sound that you’d just never heard before. That was really exciting.” He played in bands as a teenager, and tried going to college at the University of Texas at Austin but only earned three credits from taking an astronomy course, thinking it might be something he would want to pursue. But becoming a professional musician ended up being his clear choice.

Rig Rundown - Eric Johnson [2018]

Despite his high profile and staggering proficiency, plus eight Grammy nominations and a win for his 1991 tune “Cliffs of Dover,” Johnson says he’s remained conscious of not letting things go to his head, saying, “It’s better to just let it flow, like when you were a kid just loving to play,” he says. “It’s best to let that happen naturally. Once you start becoming too aware of yourself and assimilating your legacy or living in your stature or fame or notoriety, you create a feedback loop where you’ll trip over yourself eventually.”

YouTube It

Take a good look at the fretboard on Eric Johnson’s signature Virginia Stratocaster while he performs “Gem,” from his 2010 album, Up Close, showcasing a brilliantly articulate clean tone and impeccable finger work.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)