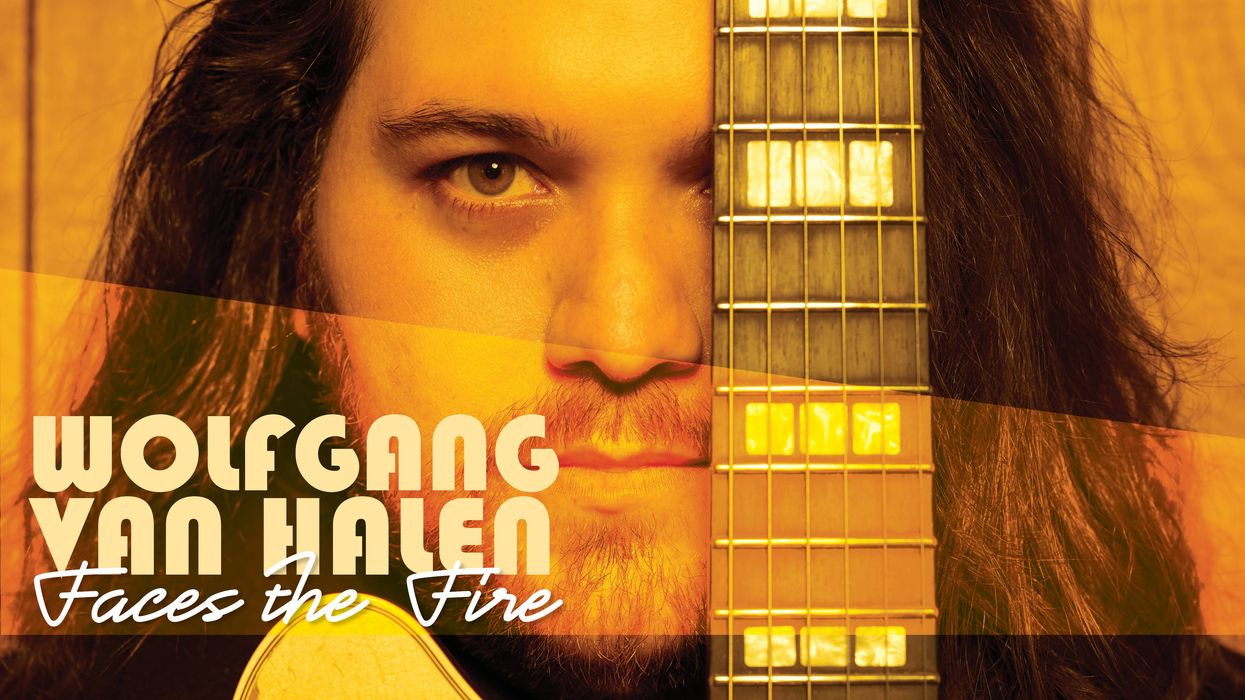

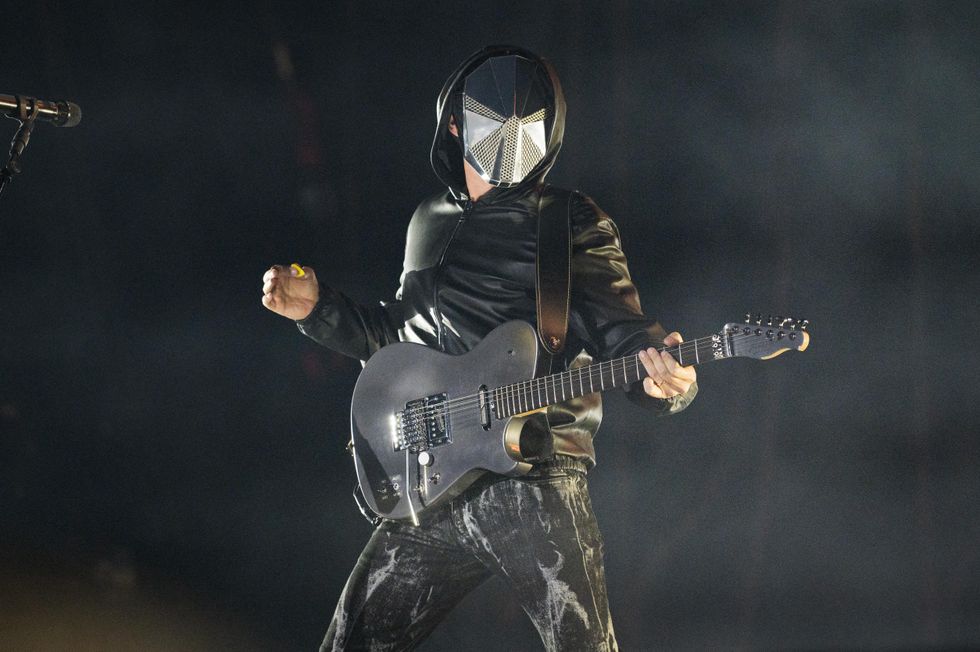

Decked out in black ninja-like uniforms with mosaic mirrored masks obscuring their faces, Muse opens their current shows with the powerful, sing-along chant of “Will of the People,” the anthemic title track off their latest album. From that song’s infectious shuffle until the very end of the concert’s encore, people are jumping out of their seats, and appear to be completely mesmerized.

Muse’s guitarist/frontman Matt Bellamy describes the song’s concept: “‘Will of the People’” is a fictional story set in a fictional metaverse on a fictional planet ruled by a fictional authoritarian state run by a fictional algorithm manifested by a fictional data centre running a fictional bank printing a fictional currency controlling a fictional population occupying a fictional city containing a fictional apartment where a fictional man woke up one day and thought ‘fuck this.’”

Muse Won't Stand Down (Live at NOVA Rock Festival 2022)

This live version of “Won’t Stand Down” (the first single from Will of the People) from the Nova Rock Festival in Nickelsdorf, Austria, sees Bellamy playing exotic melodies unaccompanied on a drop-tuned guitar to open the song up. Bellamy’s early classical influences can be heard in the secondary dominants used in the chord progression of the song’s chorus.

Fictional, perhaps, but art imitates life, and the whole vibe is connecting explosively with Muse fans upon the return of being able to experience one of the best live shows around. After all, the trio of Bellamy, bassist Chris Wolstenholme, and drummer Dominic Howard view themselves as a live band, first and foremost, and the concert experience informs every aspect of their writing process.

“It’s unavoidable for us because we’ve probably connected to our audiences more through live performance than we have through pop charts or anything like that,” says Bellamy. “We’ve never been embraced by the mainstream. I don’t think we’ve ever had a Top 40 single or anything like that. We’ve always been kind of alternative outsiders regarding recorded music, but where we connect with our audience is onstage. I think it’s totally inevitable that when we’re in the studio, almost every song we’re creating—I mean not every moment, but almost—we’re thinking about that, rather than like, ‘Oh, this is going to be on X radio station, or it’s going to be in this film.’ We’re not thinking about any of that stuff. We’re thinking, ‘We’re making this song and we’re going to go onstage and play it.’”

Bellamy has been Muse’s main songwriter since the band formed in 1994, when they were originally called Rocket Baby Dolls. After the songs are drafted, the band collaborates on production, song arrangements, and the sounds to be used on each album. Over the years, Muse has tinkered with outside producers, but for Will of the People the band decided to keep it in the family.

“We haven’t produced an album since The Resistance in 2009 and The 2nd Law in 2012,” Bellamy says. “Then, we felt like we needed some outside input, and we went to Mutt Lange for the Drones album. On [2018’s] Simulation Theory, we worked with a whole bunch of different producers. But on this album, we felt like it would be good to get back to our original process.”

“I’ve always been anti-authoritarian by nature. If you read some of my school report cards, you’ll probably find that I wasn’t the most compliant student.”

Bellamy recalls, “Lange leaned towards the human side but wanted the humans to play their parts accurately rather than use computers to repair an inaccurate performance—a very humans-first approach.” Other producers “wanted to program a drum beat and just start with that.”

Muse doesn’t operate with a singular magic formula. “Songs like ‘We Are Fucking Fucked,’ ‘Kill or Be Killed,’ and, to some extent, ‘Will of the People,’ benefit from being a bit more human sounding, a bit more relaxed, and not perfectly tight in all the different spots,” explains Bellamy. “Sometimes you can tighten the life out of a track, and we’ve noticed with Muse that could be a problem. If we make it too tight, we lose elements that we like to tap into, like chaos or feeling slightly out of control.”

The sense of reckless abandon is huge in Bellamy’s music. “I grew up on things like Nirvana and Kurt Cobain, or Jimi Hendrix. Those are the two guitarists that I probably loved the most. And the element that they brought into guitar playing was, obviously amazing guitar playing, but also an element of chaos, an element of being slightly out of control. Sometimes When you edit it out, you end up losing a little bit of that chaos feeling. That’s something that we’ve been trying to balance a little bit. It’s difficult because it’s so tempting to try to tighten everything. There was a bit of that on certain tracks. Something like ‘You Make Me Feel Like It’s Halloween,’ for example, is much more on the tighter side.”

TIDBIT: Muse returned to self-producing on their ninth studio album, Will of the People, which was recorded at the legendary Abbey Road Studios in London.

That is, until the blazing guitar solo enters. “When the guitar solo comes in, it’s really like, ‘Just let it rip. No editing,’” says Bellamy. “It was like, boom, whatever happens, happens. It’s just a balancing act with rock where you want to make sure you don’t erase the feel of it, if that’s part of what the song is trying to convey.”

Muse’s label had hinted at the band making a greatest-hits album. But for Will of the People, Muse wanted to create a new take on that concept. Rather than rummage through their discography looking for the “best” songs, Muse wanted to make all new songs for Will of the People, with the aim of making “greatest hits” in different styles. To that end, it seems like they’ve succeeded. Bellamy has said “Compliance” is the best pop track they’ve ever done, and “Kill or Be Killed” is the best prog-metal song they’ve done.

The latter will appeal to lovers of guitar pyrotechnics. It features a lethal whammy-infused, drop-tuned opening riff, Lydian pedal chords, and an over-the-top dramatic solo that could make envious shredders want to quit. But Bellamy cautions them to hold off giving up.

“If you listen to the Grace album by Jeff Buckley, you’ll notice the guitar sound is very glassy, very bright but very, very clear at the same time.”

“I’m plainly cheating in that solo [laughs],” he says. “I’m basically tapping and using a whammy pedal to do octave shifts. It sounds like I’m doing insane arpeggios. I’m not a shredder at all. I’ve never been a very good shredder, but I found ways to cut corners. On that one I’m doing a simple tapping technique, but the octave is being pitch-shifted as I’m tapping to make it sound like a really broad arpeggio.” Bellamy used this setup before to great effect on “Map of the Problematique” from Black Holes and Revelations [2006].

The Multi-Faceted Musician

Being a guitar virtuoso is far from Bellamy’s priority. “I’d say I’m a jack of all trades but not necessarily a master of one,” he confesses. Initially, in his formative years, Bellamy went down the road of trying to be a flashy, technical guitarist, but soon changed course.

“Trust me, there are thousands of guitarists on Instagram that are way better than me [laughs]. I see them all the time. I sort of realized I was never going to be like Steve Vai or something. To me, probably where my specialty is, is in playing guitar and singing at the same time. That’s something I’ve had to work on quite a lot because it’s hard—at least it was hard for me in the early years. Especially playing certain rhythmic parts or rhythmic patterns and detailed kind of singing. That’s what I focused on. Sometimes you have to work out where your upstroke is on the guitar and how that connects to which syllable of the vocal.”

Bellamy has always been less myopic than his peers in the guitar community. Starting in his late teenage years, he had a dual musical personality. On one hand he was in bands that were all about rock, U.K. Indie music, and grunge, but on the side, he would be at home listening to classical music. “I just loved it,” says Bellamy. “I was getting into the electric guitar, but in my school there was a classical guitar teacher. That was the only guitar teacher who was available, so I decided to just go down that road because I was already playing guitar a little bit. I learned about different modes and scales, and different ways of moving chords around. I studied a bit of [Heitor] Villa-Lobos and learned a little bit about that back then, but I never really became serious in the classical realm, guitar-wise. I did it for a couple of years and then, through listening to that stuff, it led me to discover great piano composers, like Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, and Liszt.”

Matt Bellamy’s Gear

Muse’s Matt Bellamy makes a point with his main axe, a Manson DL-1.

Photo by Hans-Peter Van Velthoven

Guitars

- Manson 007 MB

- Manson ORYX custom fanned-fret 6-string

- Jeff Buckley’s 1983 Fender Telecaster

- Manson MB Drone 003 with Manson PF-1 bridge pickup and Sustainiac

- 1966 or ’65 Gibson LG-0 acoustic

- Manson MB Standard with Manson PF-1 Humbucker Bridge pickup and Sustainiac in satin “Matt Black” finish

- Manson MB Standard with Manson PF-1 Humbucker Bridge pickup and Sustainiac in gloss “Red Alert" finish

- TogaMan GuitarViol Bastarda

Microphones

- Sennheiser MD 421

- Royer R-122V

- Neumann U67

- Neumann U87

- Shure SM57

Amps

- Diezel VH4

- Mesa/Boogie Badlander

- Marshall Handwired 1959 Super Lead plexi (modded)

- Orange Rockerverb 100 MKIII

- Gibson EH 150 (1940)

- 1964 Vox AC30 Top Boost

- Laney 100-watt Klipp head and 4x12 cab (1972)

- Universal Audio OX Amp Top Box

- Mills 4x12 cabinet with Celestion V30 8-ohm speakers

- Marshall 1960BX handwired 4x12 cabinet with 25W Celestion Greenback 16-ohm speakers

Effects

- Dwarfcraft Necromancer

- Pro Co RAT

- Death by Audio Total Sonic Annihilation

- Korg SDD-3000 digital delay

- Pete Cornish TB-83 treble boost

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball (.009–.012–.016–.026–.036–.050)

- Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

While Bellamy is the band’s sole guitarist, he is completely fine with not including the guitar on everything Muse. He’s made it a point to also showcase piano, and the instrument plays prominently on the new songs “Liberation” and “Ghosts (How Can I Move On).” The latter is the big piano number on Will of the People and opens with an arpeggiated keyboard figure similar to Adele’s mega-hit “Someone Like You.” This song indirectly spawned from a small solo side project Bellamy was working on over the last several years, which mostly saw him redoing Muse songs with just piano and vocals.

“That is what led to that song,” recalls Bellamy. “That was the first time I really tried to do a simple piano/vocal ballad. I guess you’re always going to be in the company of people who have had big hits with those kinds of things. For us it was a bit of an unusual move. I’ve always had piano here and there, but never really a song that’s just vocal and piano. To be honest, I played the song for the guys in the band, and we weren’t sure if it was going to be on a Muse album. But they really liked it and we thought, ‘You know what, this adds a little bit of color, so maybe it can be on.’ I’m not sure yet to what extent it will be played live.”

The Manson Connection

In his time away from the stage and studio, Bellamy keeps himself very busy. In 2019, he became the majority owner in Manson Guitar Works and is very involved in everything from overseeing all the new designs to going to the shop and meeting new employees. “It’s great. I love it. It’s a local business in the area I’m from in England. When I was growing up in Devon, South West England, there was a guitar shop in Exeter, which is the nearest college town. It was kind of the best guitar shop really,” says Bellamy, who, as a teen, lusted after a Manson custom build.

Muse - WON'T STAND DOWN (Official Video)

“I bought my first couple of guitars from there, but I couldn’t really afford the custom-made ones. We found out that the guy who ran the place, Hugh Manson, used to be Led Zeppelin’s guitar tech. He’s a luthier that makes his own guitars to whatever spec you want. So, as soon as Muse had any kind of success and I could afford to buy a nice guitar, around the year 2000, I went to him and said, ‘I’d love to have a custom-made guitar.’”

Bellamy’s first custom Manson was an aluminum guitar, with a finish similar to a DeLorean and a Z.Vex Fuzz Factory and MXR Phase 90 built in. “It became my main guitar from about 2001 onwards. Then I went back to him to get a couple of others that were similar in shape. I designed the shape. I wanted a unique shape that hadn’t been seen before. I worked with him on custom guitars throughout the 2000s and this just went on and on, to the point where all the guitars I use onstage are Manson guitars. Then, around four or five years ago, Hugh retired and wanted me to take over ownership of the company, to keep it running, and to take it to the next step.”

Manson sells a good amount of custom guitars, but the big seller is the Manson Meta Series MBM-1, which comes in at the lowest price point. “That was something I introduced to the company when I took over. I really wanted there to be a more affordable version available,” explains Bellamy. “We have some of those parts manufactured in Europe and some in Indonesia, and we have those parts brought to our warehouse in Devon where we put them together ourselves. The more expensive ones are handbuilt and handmade in the factory in Devon. Since the last 20 years, he’s employed a bunch of amazing guitar makers. There’s an amazing workshop where people hand-make these things.”

Matt Bellamy prefers an element of chaos in his music, which Muse mirrors in their thematic tours and potent onstage presence.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

While Bellamy is mostly a Manson loyalist, he employed a unique instrument called the GuitarViol for the pizzicato string parts in the verses of “Won’t Stand Down.” “It’s got a similar range as a guitar, only a few tones up from where a cello is based. When you play it, it sounds a bit like a cello,” he says. “I’m not a fretless player. It’s a way of adding string sounds to songs. I was playing it like I play a guitar or bass. It’s a cool instrument because, rather than using sound libraries, I just played that instrument.”

Bellamy also recently indulged in the purchase of a trophy instrument: Jeff Buckley’s 1983 Grace Fender Telecaster. Rather than store it away in a glass case, Bellamy uses the instrument quite often. “It appears a couple of times on the album and I love it. It’s a great guitar. Rather than just stick it on the wall, I think it’s nice to give it some use and keep it involved in music,” says Bellamy. “I used it on ‘Will of the People,’ on the lead part, which is the high bluesy bit. I may have used it on the verses of ‘We Are Fucking Fucked’ as well. It’s such a great instrument. It’s just a unique, strange-sounding Telecaster. I had it looked at by the Manson team and they were saying there’s something odd about the pickups. They seem to be slightly out of phase, and it causes this very glassy tone. If you listen to the Grace album by Jeff Buckley, you’ll notice the guitar sound is very glassy, very bright, but very, very clear at the same time.”

“If we make it too tight, we lose elements that we like to tap into, like chaos or feeling slightly out of control.”

Populism and Power Struggles

Many songs on Will of the People, such as the title track, “Compliance,” “Liberation,” and the closer, “We are Fucking Fucked,” revolve around matters of oppressors and the oppressed. “I think it’s a theme that you can find across Muse’s career. It’s part of my nature,” explains Bellamy. “I’ve always been anti-authoritarian. If you read some of my school report cards, you’ll probably find that I wasn’t the most compliant student. I’ve always been kind of skeptical of power structures and those that have power—the concentrated few who take advantage of their power over the masses and so on. It’s not one particular thing that I’m aiming at. It doesn’t matter where it exists, I have a natural inclination to feel like that should be always disrupted.

“You can apply that to anything from corporate structures, banking structures, economic structures, to political structures. Any structure where a concentrated few have incredible power over a large population. I’ve always been intrinsically questioning that and wondering about the quality of the people who are placed in those positions of power, and how did they get there? It’s been a lifelong fascination for me, and it’s obviously translated into the music and the songwriting, going back as far as songs like [2009’s] ‘Uprising’ and so on. It doesn’t matter where they exist. The fact that extreme wealth can be concentrated in a handful of tech entrepreneurs, for example. Or the fact that powerful lobbyists can have such an influence on senators.”

Having lived in L.A. since 2010, Bellamy gained new insight into the class politics that divide America, and this seeped into many of the songs on Will of the People. “During the troubled period of the crossover from January 6, and when all that stuff started to fall apart, it kind of played into this idea that populism can actually be quite scary,” says Bellamy. “When the masses do topple something, it can be quite chaotic and crazy as well. On the one hand, the masses overthrowing power structures is appealing, on the other it can actually be quite frightening. This album explores both sides of that.”

Muse - Map Of The Problematique [Live From Wembley Stadium]

Matt Bellamy employs effects in uncommon ways to achieve his musical goals. “Map of the Problematique” was the first time that he used whammy pedals. “I basically sent a program to make it turn on and off in a certain rhythm,” explains Bellamy. “So, it would make the octave change in a rhythmic pattern. For example, in ‘Map,’ I’m just playing a power chord, but it goes (sings fast arpeggiated repeating phrase) and that’s kind of a program telling the whammy pedal to change octaves. I used that same technique for the solo on ‘Kill or Be Killed.’”

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.