If you ever find the opening to ask a composer or producer what it means to “paint with sound,” be prepared to frame the question in as many different ways as there are colors in the visible spectrum. Inspired by synaesthesis? Could be. Maybe a deep dive into abstract free-form improv? Sure, always worth a shot. What if you commit to exotic tunings or unconventional music theory? Or how about a mash-up of prepared instruments with some radical effects processing and tape manipulation?

We can do this all day, but before we lean into an “all of the above” approach, consider this: The only limit, really, is your imagination—or, more suggestively, your dreams. “There’s a way to get to that psychedelic state without actually taking psychedelics, which is useful,” Roger Clark Miller explains, with just a glint of conspiratorial humor. Given his illustrious history as a post-rock guitar guru and multi-instrumentalist with influences that range from ’60s acid rock to avant-shred to modern classical, Miller is intimately familiar with what it takes to push any and all boundaries in search of the music he hears in his head.

“The first time that I actually did something interesting with it was back in art school,” he recalls, paying tribute to his teacher Denman Maroney, a legendary jazz outsider known for his work with prepared piano. “He saw my interests and thought I’d probably like surrealism. Up until then, my idea of surrealism was taking acid [laughs].”

After reading André Breton’s surrealist manifestos (the second one, in particular, which touches on dreams as a creative reservoir), he set about applying the techniques to making music—and ran into a roadblock. “Breton actually said because music isn’t so specific, it can’t be surrealistic. And that kind of pissed me off. I was looking for a way to compose, and I didn’t want to use what had come before. I thought, well, if I make music based on dreams, then I can create a surrealistic music, and bypass Breton’s megalomania—as much as I respect him! This gave me access to a very organic structure. Everybody dreams, and there are forms to it.”

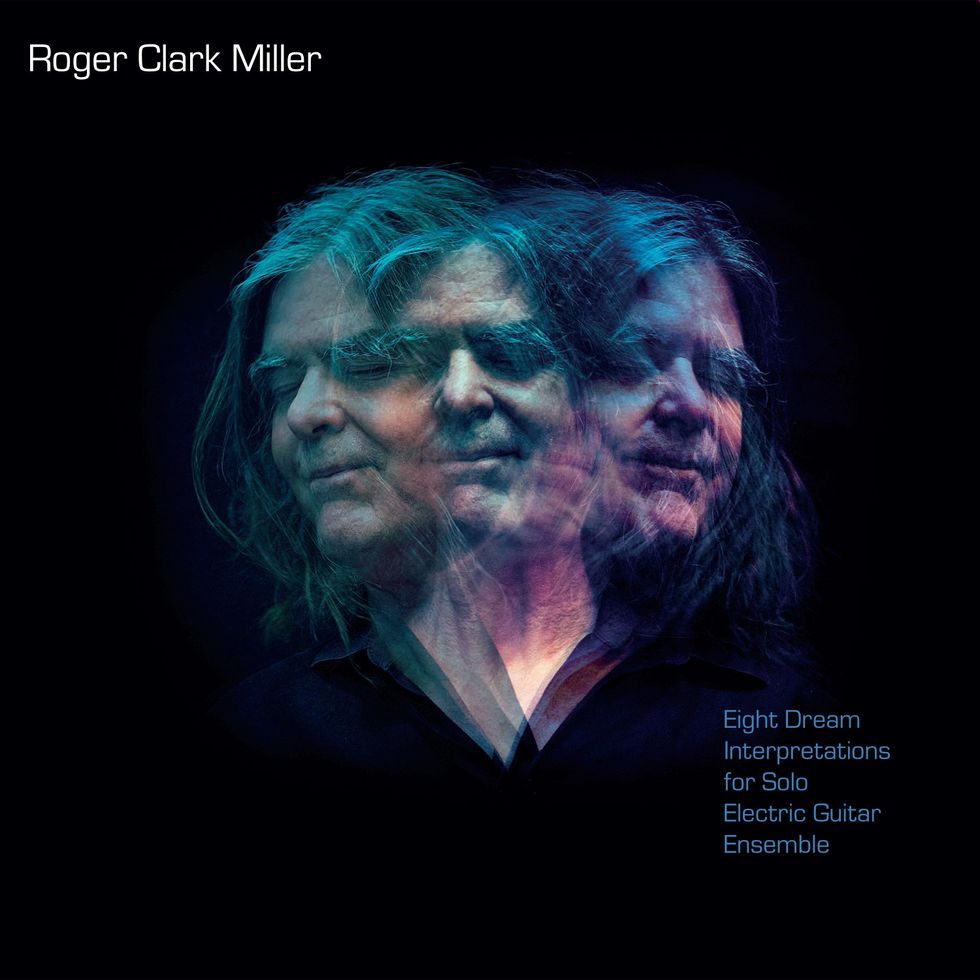

Miller’s jauntily titled Eight Dream Interpretations for Solo Electric Guitar Ensemble, released earlier this year on the Cuneiform label, is in many ways the culmination of the technique he started developing back in 1975, when he created his first piece for solo violin. Miller has kept dream journals for decades, and uses them primarily as a non-linear source for ideas that he fleshes out into musical compositions. (“I don’t actually hear music unless it was part of the dream,” he points out.)

“This kind of music rewards attentive listening because it’s really composed and thought-out, so you’re not gonna be bored.”

If all that sounds a bit abstract and even esoteric, keep in mind this is the very same guy who co-founded Mission of Burma, one of the most viscerally immediate post-punk bands to come out of Boston’s raucous underground scene in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Back then, Miller adopted the much reviled Fender Lead I as his axe of choice, figuring he could put his personal stamp on it. As it turned out, the guitar’s cheaper construction and single split humbucker was perfect for sculpting an angular, aggressively jagged, but still bluesy sound through a vintage Marshall JMP-50 combo.

Miller was also a founding member of the somewhat kinder and gentler group Birdsongs of the Mesozoic, in which he played piano. (Due to his early struggles with tinnitus, he had to bow out of Burma in 1983, but the band reunited in 2002 for four more albums.) All this history and plenty more feeds back into the making of the Dream Interpretations, for reasons that Miller loves to elucidate.

Miller’s goal for his new album was to bring his surrealistic dreams in sound to life. His most recent tools for this task include three Rogue RLS-1 lap steel guitars and a Boomerang III looping system, which he uses in tandem with the Side Car controller footswitch.

“With my friend Martin Swope,” he says, name-checking Mission of Burma’s resident sound technician and live-tape-looping scientist, “like everybody, we were pretty fascinated with Brian Eno’s work at that time. Martin wanted to do a Robert Fripp and Eno style thing, so he had me play this amorphic, modal piano piece that I wrote, and he made these guitar loops going around and around. That was for Birdsongs, but he and I had worked like that on the song ‘New Disco’ [for Burma]. That’s how he became part of the band.”

Over the years, Miller folded what he learned from Swope into the sound he was chasing. In the early ’80s, he acquired an Electro-Harmonix 16-second digital delay. “It’s truly one of the most unique devices ever made,” he says. “It’s so unique that I used it as my pivot for quite a few years. I still have it, but its biggest drawback is the memory. If you make something longer than a two-second loop, the fidelity degrades. Back in 1983, memory was not cheap.”

“With looping, you can hear a sound and you don’t know when it happened or what instrument did it.”

The effect figured prominently in the making of his 1995 solo slab, Elemental Guitar, which he tracked using what was then a recently acquired ’62 Strat reissue. The album also features two pieces, “Dream Interpretation No. 7” and “Dream Interpretation No. 8,” that Miller considers to be successful precursors to his current album.

More than 25 years later, Eight Dream Interpretations opens with “Dream Interpretation No. 16,” a chilling excursion that suggests a serpentine path being resumed, although much has changed in the interim. For starters, Miller has added three Rogue RLS-1 lap steel guitars to his arsenal: one tuned to unison E and used exclusively for slide parts, and the other two prepared with alligator clips and strung with different gauges to capture a wider palette of tones. He’s also mothballed the Electro-Harmonix in favor of a Boomerang III looping system, which he uses in tandem with the Side Car controller footswitch.

Roger Clark Miller’s Gear

Besides looping and other effects, plus his trusty Stratocaster, Miller relies on a trio of lap steels to create his celestial soundscapes—in three different tunings.

Photo by Roger Clark Miller

Guitars

- 1990 Fender Stratocaster ST62 reissue (made in Japan)

- Rogue RLS-1 lap steel (three: one tuned to unison E and used as a slide guitar, two others prepared with alligator clips)

Amps

- Fender Deluxe Reverb (two)

- Sunn bass head with 610L cabinet

- Peavey Classic 50 410 combo

- Walrus Audio MAKO Series ACS1 Amp and Cab Simulator

Effects

- Electro-Harmonix 16-Second Digital Delay

- Boomerang III Phrase Sampler with Side Car controller

- TC Electronic Brainwaves Pitch Shifter

- TC Electronics Rush Booster

- Electro-Harmonix East River Drive

- Source Audio Kingmaker Fuzz

- Ernie Ball stereo volume pedal

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.46; Strat)

- D’Addario EXL 157 (.014–.069; lap steel)

- D’Addario Medium EXL 160 (.050–.105; lap steel)

- Dunlop Max-Grip .73 mm

Along with his trusty Strat, when Miller seats himself behind the Rogues it’s as though he’s strapping in for an interstellar journey at the helm of a homemade time machine. And the music comes across that way, from the dueling dive-bombing waves and high-pitched jet washes of “No. 19” to the softly percussive melodies and clean, pitch-shifted guitar lines of “No. 18.” (The tracks are sequenced as any album would be, not in numerical order, but according to the listening experience Miller wants to establish.) Outfitted with various effects that he dials in with the precision of a surgeon, Miller literally choreographs each move he makes to create the music. It’s mesmerizing to watch him in the video, directed by filmmaker Jesse Kreitzer, that accompanies “No. 17”—a wildly cinematic and soundscape-y piece that’s driven by a persistent, pulsating rhythm and a haunting sci-fi melody straight out of vintage Doctor Who.

When asked about influential recordings that have inspired him, Miller’s tastes run eclectic, to say the least. Fred Frith’s groundbreaking Guitar Solos album, an experimental classic, is “just an amazing work. I learned about using alligator clips from that album.” And then there’s the 1982 minimalist epic Descending Moonshine Dervishes by Terry Riley (“the first honest looper,” he says). But when it comes to specific guitar players, there are two in particular who move him to rapture.

The reunited Mission of Burma—guitarist Roger Miller, drummer Peter Prescott, and bassist Clint Conley—at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in London, England, in 2004.

Photo by Neonwar/Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

“See, I’m a little older than some of your readers here,” he warns, “but I came to my creative start during psychedelia and the British Invasion, so my heroes were Syd Barrett and Jimi Hendrix. I mean, Jimi was like a bolt of electricity from who knows where. He embraced the electric guitar as an instrument that could explain all sorts of alternate realities, and he wasn’t the first to use feedback, but he walked into it with complete conviction and cut a path for others to follow.

“And whereas Hendrix was a true guitar master, Barrett was considerably less skilled, but his vision, when operating on all cylinders, just transcended the limitations. For him, sound and vision were more important than technique. He was also a painter, and that may well have had something to do with it—painting with sound indeed! His solo on ‘Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk’ was once described to me as the ugliest guitar playing anyone had ever heard. Not for me!”

“I came to my creative start during psychedelia and the British Invasion, so my heroes were Syd Barrett and Jimi Hendrix.”

With ears wide open, Miller is constantly exploring new directions. His most recent composition, the nearly self-explanatory Music for String Quartet and Two Turntables, has just been recorded with members of Boston’s Ludovico Ensemble. He also has a new album in the can with Trinary System, the rock trio he founded in 2013, planned for release next year. Whether he’s painting with sound or testing the very elasticity of time, his multidisciplinary method of mining his dreams and looping the sonic events of his waking life continues to yield dividends.

“I don’t really think about it per se,” he clarifies, “but certainly with looping, you can hear a sound and you don’t know when it happened or what instrument did it. That’s when looping messes with time. And then in dreams, time is elastic, too. So perhaps it’s a mixture of those things. To me, this kind of music rewards attentive listening because it’s really composed and thought-out, so you’re not gonna be bored. But it does also work for me as an atmospheric, swirling clouds-in-the-room kind of thing. That makes me happy.”

Mission of Burma - Laugh The World Away (Live on KEXP)

Stripped down to their punk rock essentials, this 2009 in-studio performance finds the reunited Mission of Burma line-up of Roger Miller, Clint Conley, and Peter Prescott giving the next generation a hard act to follow. Miller carves out a relentlessly knife-edged distortion with a battle-tested Fender Lead II.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)