From the British Invasion of the ’60s to the punks of ’77 to the nascent days of heavy metal and shoegaze, the U.K. music scene has often been the harbinger of what’s next for guitar. To many, Bristol-based post-punk unit Idles’ music represents that next step. Idles’ albums are confrontational, heartfelt, politically outspoken, and don’t sound like anything else. The band’s 2018 release Joy as an Act of Resistance hit the top five in the U.K. charts, enjoyed nearly universal critical acclaim, and earned the group a Mercury Prize nomination.

While many critics focused on Idles’ enigmatic frontman Joe Talbot’s poetic lyrics and brash delivery, Joy as an Act of Resistance was full of writhing, rhythmic, anti-rock guitar work that was equal parts clever and reckless—via guitarists Mark Bowen and Lee Kiernan. (Drummer Jon Beavis and bassist Adam Devonshire complete the band.) It was a blast of fresh air at a time when many popular rock bands had lost their teeth, were boiling their songwriting down to an algorithm, or were wistfully mining the genre’s past.

In a small brick room deep in the bowels of La Frette Studios—tucked away just outside of Paris—Idles and producers Nick Launay (Killing Joke, Public Image Ltd, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds) and Adam “Atom” Greenspan (Refused, Anna Calvi) crafted and honed Ultra Mono, the highly anticipated follow up to Joy as an Act of Resistance. Bowen and Kiernan took a decidedly different and novel approach to penning the new album’s 12 songs. The pair began the writing process by defining a sound palette for the album via pedalboards populated with some of the least musical and weirdest stomps they’d each collected. Over-the-top fuzzes, alien-sounding filters, and a boutique glitch box from Belgium all played a major role. The anti-shredders’ effects experiments were the direct starting point for much of Ultra Mono’s songs and guitar parts—many of which Bowen confesses “really wouldn’t sound like anything without the effects.” The album’s lead single, “Grounds,” is a great example of this effects-first approach. It’s an anthem of solidarity for the anti-racism movement, built on the back of a lone repeated note played through a Red Panda Raster delay. The song is an exercise in weaponized simplicity and atonality, yet somehow wildly catchy.

Kiernan and Bowen often use the guitar like synthesists or drummers on Ultra Mono, harnessing the percussive side of the instrument as a trigger and controller for the sounds they coax out of their pedal menageries. Relying on effects-processed rhythmic passages in the same way a producer uses samples gives the albumthe rhythmic bounce and swagger of hip-hop, but presented with the snarling sonics of a rock band playing through high-powered tube amps at full tilt. That trick was further helped along with a dose of post-production magic by producer/engineer Kenny Beats, who added programming and was part of an arduous four-month mixing process.

The result is that Ultra Mono is a whirlwind of hulking fuzz, clanging dissonance, synth-inspired bleeps and bloops, and notes bent so far out of shape that they’d break if they were bones. While there’s an underpinning of dry garage-rock rhythm 6-string that helps propel this effects-laden guitar colossus and provides counterpoint, it all comes together to make something genuinely original. As we enter the probable peak of the effects-pedal renaissance, and at a time when our collective reality is just too absurd for loud rock bands to not have something of substance to say, Ultra Mono is a record deeply representative of the moment.

Despite Ultra Mono’s anger and serious subjects, Bowen and Kiernan are affable gear nerds that don’t take themselves too seriously. The pair have even taken advantage of the unexpected downtime Covid-19 has foisted upon us by starting their own phonetically named YouTube series, Genks, which finds the duo exploring the inner workings of Idles’ tunes, their favorite effects, and interviewing notable guitarists that they mutually dig.

Premier Guitar caught up with Idles’ pedal pushers by phone to discuss their effects-based approach to writing Ultra Mono, the exotic and mundane gear used to craft their band’s latest, how Gang of Four, Electric Wizard, French DJs, and Wu-Tang Clan all found their way into the sonic stew, and how seemingly useless sounds can make great music.

You’ve said the guitar tones on Ultra Mono arelike weapons and that the album was written around sounds rather than riffs. That really shows in your playing, which is often primitive and rhythmic—like you’re acting like drummers.

Lee Kiernan: That was a goal. We wanted to have a lot more rhythmic power and work as a team towards that. A lot of the time, songs started with bass and drums, because that’s always the backbone of our music, and we’ll push those ideas with guitars to make it bigger. Something we really tried to do on this album that we didn’t do in the past is give each other space and also focus on playing together. Bowen and I play as a unit together a lot on Ultra Mono—often playing the same thing at the same time to add more emphasis and power to a single idea.

Mark Bowen: When we set out to make this album, there was something about rock sensibilities and production that had too much deference to the guitar and how we felt the guitars should sound. The thing about guitars is, frequency-wise, they can kind of get in the way of everything. What we really wanted to do is have the guitars either play percussively or play to support the bass. Otherwise, the frequency bandwidth of the guitars was narrowed down to allow other things to really pop in the mix. The opposite also happens a lot on the album for an effect, too, where the guitars deliberately take up all the frequency real estate for impact. All of these tracks were really written around the idea of us all supporting one musical part at a time. That concept was key during the writing, so the recording process was really about making sure that each of the instruments had the impact and weight we wanted them to have.

TIDBIT: “The mix on this album was so much of the trick, and we took four months to mix it,” says co-guitarist Mark Bowen. “We wanted that hip-hop edge.”

Flourishes of atonal guitar are a huge part of Ultra Mono’s sound. How much of that noise-making was baked-in from the songwriting process, and what was the overall approach to experimenting with effects and noise-making in the studio?

Kiernan: Most of it. Bowen and I are always on the hunt for new pedals that are weird. When we were writing this album, we’d go to random guitar shops and ask them for the weirdest pedals they had. It may sound useless, but it still might touch you somehow. Every now and then, a pedal that does something really weird will kick you into gear. Or sometimes you just need to slam a weird pedal with some fuzz or find the weird noises hiding in it. We’ll both admit we’re not the best guitarists and relying on sound-making is our key and really a major part of what we do.

Bowen: The noise-making had to be thought of from the start. We basically created a sound palette first, and once we created a sound, that sound informed the riffs. The riffs on this one really wouldn’t sound like anything without the effects we used. So there was a lot of time spent tweaking, but it was really important to the overall writing of the album.

Do you have any advice on finding the musically useful ideas hiding in deliberately ugly-sounding effects?

Bowen: I think you hit the nail on the head when you said we’re all playing almost like drummers. If you’ve got a sound that you initially feel is musically useless, try using it rhythmically and use it as an adjunct to a snare hit or use it where a high-hat might be in an electronic song. It sounds like nothing else when you replace drum parts with a weird guitar sound. Another big thing is if you get a sound that you think is great, but you can’t necessarily see a traditional musical place for it, building a song around that sound is a big thing for us. If you look at “Danke” and the sound that almost sounds like a piece of metal being whipped in the middle of that, that sound was the starting point for that song.

Kiernan: A lot of what I use is fuzz, and I especially like the ones Death By Audio makes. They’re punishing. Their pedals are just brutal and I like to slam fuzzes into different things to get unique sounds. Essentially what I do a lot of the time in this band is find a big noise and then bend the strings to make it sound like something alive and dynamic more than just a blast of noise.

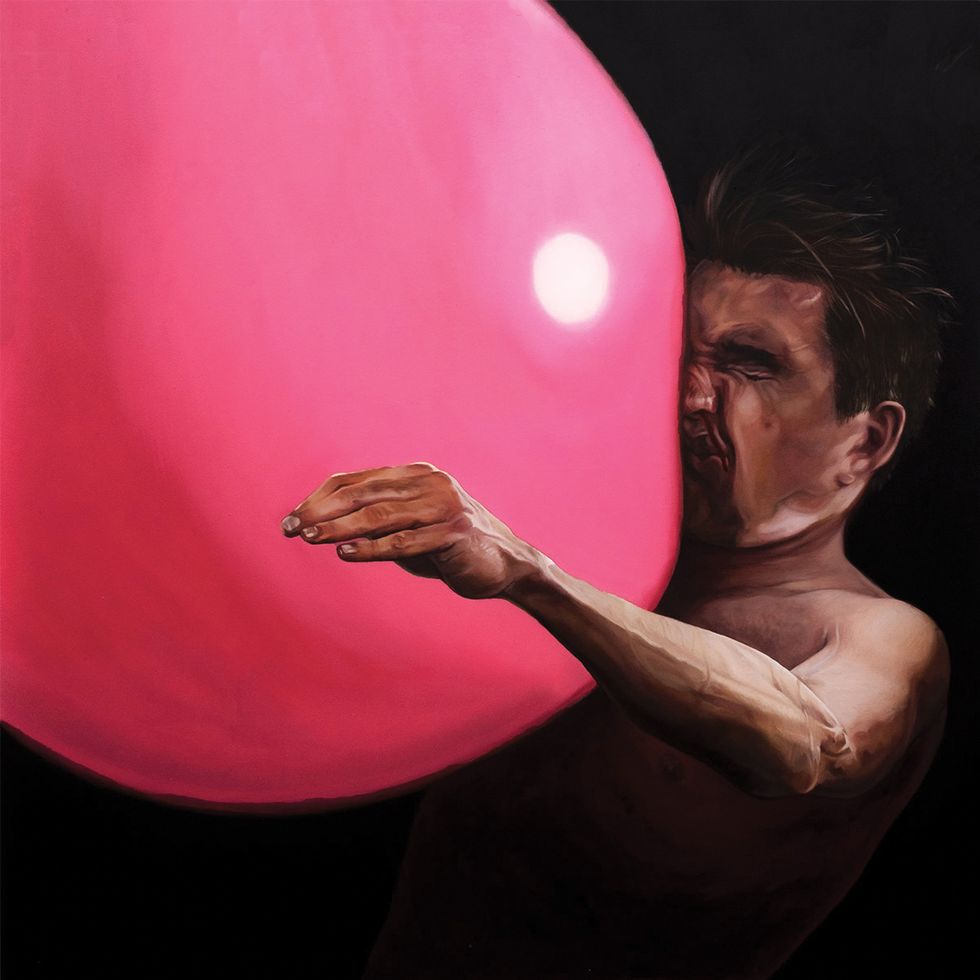

Mark Bowen lays down a strummed layer of sound with one of his Strats. A regular Fender on Idles’ recordings is a brown-finished 1972 model owned by his father and named Stinky. Photo by Debi Del Grande

The noise and dissonance on Ultra Mono works in a harmonious and cohesive way. That has a lot to do with how you guys use negative space, but are there any other tricks to tying all of the din together to make something musical?

Kiernan: The dissonant and atonal stuff is something Bowen and I have always done and we love working together on. On this album, some of the parts are simpler than things we might have gone for in the past, but they’re much more powerful, and I think that comes from being much more considerate of what each person is playing.

Bowen: “Mr. Motivator” is a good example: Lee makes this “genk” noise that sounds like a hammer in a metal factory, and he plays that along with the drums, and that part really only occupies a frequency range around 1.2k to 2.3k—which is a large bandwidth, but it’s where the transients of the drums and the cymbals sit. That part really pops in that space. For it to not sound like just noise, we stripped everything back so that it was just a guitar part that almost made sense on an acoustic, then slowly added in effects from the sound palette that we’d put together for this album.Adding those sounds in slowly helped us to not overdo it or make things sound like a Hoover or an old dial-up modem. We also wanted to avoid the guitar coming off djenty, so we needed to make sure the amps had enough headroom and that there wasn’t any unnecessary distortion. We actually went straight into the Neve [A646] desk at La Frette a lot because there was enough dissonance baked into some guitar parts that we didn’t need to make it worse by getting caught up with amps and pedals.

So, a dry, direct-to-desk guitar track gave the guitars some body when the effects would get overwhelming?

Bowen: Yeah, that or the Fender Twins. I can’t express how amazing sounding that Neve desk was when we plugged certain guitars into it. I have a new Fender Player Series Strat that I loaded with Red ’79 pickups by the Creamery, from Manchester, U.K., which is a very trebly Strat pickup that sounds like Gang of Four no matter what you’re plugged into. I used that pickup a lot for dry sounds that propelled things forward under the effects. Also, any time there’s chords on the album, they’re played with down-strokes the whole time to really make sure they had that Strokes/Ramones kind of chop. Propulsion was a word we used a lot in the studio.

Kiernan: There’s nothing more choppy or natural sounding than going straight into the desk, and you can really hear the person playing when you record that way, and if you add that in with everything else it tightens up the effected guitars.

Can you guys detail your main amp rigs for the album and any additional amps that made a big impact on the overall sound of the guitars?

Kiernan: The main combination was really my live rig, which is a reissue 100-watt Marshall Super Lead plexi and 100-watt Marshall JCM800 2203 going into two Marshall 2x12 cabs loaded with Eminence Swamp Thang speakers. Then a reissue Fender Twin Reverb. I have the Marshalls running as loud as I can have them and they’re generally quite gainy like that, but my 800 is a master volume model and I dial the gain back a bit on that so I can attack it a bit harder.

Bowen: My core amp setup was my Hiwatt DR103 going into a Hiwatt 4x12 loaded with Celestion Creambacks, and then I used a Sunn Model T that we actually borrowed from the band Sunn O))), and we had that running with everything on 10 going into a Hiwatt 2x15 cab. I also ran a Fender Twin Reverb or this really beautiful Mesa/Boogie Mark II combo, which really took pedals beautifully. That was my main setup, and then we’d jump around through a couple of different amps for the trashier, more garage-y songs—usually this really beat up ’70s Fender Princeton Reverb.

Could you tell me about the main guitars that really played the hero role on Ultra Mono?

Bowen: My Electrical Guitar Company EGC 500 was the one. That guitar has just changed the game for me. It’s got an acrylic body and aluminum neck, and it’s everything that I want out of a guitar. It’s so much louder than other guitars, and there’s this resonance to it that really fits in with my ethos and songwriting. It sounds like an angry piano. That guitar is capable of really horrible caustic sounds, but immediately switches over to making these weighty, thuddy doom-metal sounds.

Guitars

Electrical Guitar Company EGC 500 acrylic body

1972 Fender Stratocaster known as “Stinky”

2019 Fender Player Series Stratocaster with the Creamery Red ’79 pickups

1971 Fender Musicmaster

’90s Fender Custom Shop Bajo Sexto Telecaster

Amps

Hiwatt DR103 Custom 100 reissue

’70s Sunn Model T head (silver-knob era)

Hiwatt 4x12 loaded with Celestion Creambacks

Custom 2x15 cab

2019 Fender ’65 Twin Reverb reissue

Mesa/Boogie Mark II combo

’70s Fender Princeton Reverb

Effects

Red Panda Raster

Red Panda Particle

Moog Minifooger MF Ring

Moog Minifooger MF Delay

ZVEX Super Duper 2-in-1

ZVEX Lo-Fi Junky

Electro-Harmonix POG2

EarthQuaker Devices Acapulco Gold

Death By Audio Reverberation Machine

Death By Audio Echo Dream 2

Death By Audio Waveformer Destroyer

Adventure Audio Dream Reaper

Recovery Effects Sound Destruction Device

JHS Haunting Mids

The GigRig ABY-Baby

Boss TU-3W Waza Craft Tuner

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Mammoth Slinky (.012–.062)

Dunlop Tortex Standard 1.14 mm purple

For Ultra Mono, Bowen also used celluloid 1.14 mm picks and a metal pick on certain tracks

Lee: I basically used a Fender Tele with just a bridge pickup wired straight to the volume pot for most of what I did. Most of my Teles or Esquires are loaded with various Bare Knuckle pickups. They’re pretty much all regular single-coils. Humbuckers tend to be too bulky and aggressive for what I do, and tend to get too thick sounding when run through all of the effects. And I like my dry tone to be thinner and kind of harsher.

What pedals were really integral to Ultra Mono’s sound palette? Are you guys doing anything weird with your switching or effects routing or running your amps in stereo?

Kiernan: When we record, it’s our live boards and done in a way that translates easily to playing these songs live. If we’re doing overdubs, then we’ll swap things out to find something that’ll hit the mark better. All of the effects go to my Marshalls and, on the record, the Twin just got a Boss Blues Driver to push it a bit, but it was very clean and punchy. The idea was that the Twin gave me that rhythmic chop like you hear on the chorus of “Reigns” and the chorus on “Mr. Motivator.” I also used a ’70s Peavey Pacer for that same kind of clear rhythmic chop. Solid-state amps just have so much less fizz and their clean tone can be so sharp. The pedals that I used most were the Death By Audio Interstellar Overdriver Deluxe for pretty much every fuzz sound, and that was always paired with an EarthQuaker Devices Arrows boost to push it over the edge. That can be heard on “Reigns,” for the feedback in the verse, my solo on “War,” the outro on “Anxiety,” and pretty much anything else that I do on the album that’s really fucked-up sounding. The EarthQuaker Arrows and Tone Job were used together on pretty much anything that is calmer sounding, but wasn’t done straight-to-desk. I also used a Stamme[n] by drolo, which is this absolutely insane pedal company from Belgium. The Stamme[n] makes some of the weirdest, most fucked-up noises by latching onto notes and then basically tearing the frequencies apart for really weird electronic sounds, and I used that for the pulsating overdub on “The Lover.”

Bowen: The pitch-shifting delay on “Grounds” is the Red Panda Raster, and that riff is really just one note through that pedal. That pedal does the octave down you hear on the first half of “Grounds,” and I switch it to the octave-up function for the second half. That pedal is just really good at making very simple synthesized-sounding tones without being overly 8- or 16-bit sounding, or being overly modulated or sounding like it’s got a ring mod in it. It also doesn’t have a lot of white noise or hiss, but it still makes a sound that just doesn’t normally come out of a guitar. The ZVEX Super Duper and the JHS Haunting Mids were really important for carving space and making sure the amps were cutting, especially on the cleaner-sounding stuff. The Death By Audio Reverberation Machine was used a lot. There’s something amazing about everything Death By Audio makes, in that they really respond to how much you’re digging in when you’re playing. The ZVEX Instant Lo-Fi Junky is another hero pedal. It’s all over [2017’s] Brutalism and Joy as an Act of Resistance,and it was used selectively on Ultra Mono for that nice warble it gets. Sometimes I’d just leave it on for an overdub without even playing anything because it gives this nice warble in the background and adds some crappiness to the overall sound.

Unfortunately, I’m doing all my switching manually, so it’s a lot of jumping around and heel-toe kind of stuff. Routing wise, nothing super unusual. My pedal chain is a little weird in its order, but I send everything to all the amps all the time. My amps are EQ’d in dramatically different ways, with one more focused on bass sounds and one handling brighter tones.

With their blend of savvy hip-hop and electronica studio-mixing techniques, and a raw, high-energy live show, Idles has all the bases covered. Here, Lee Kiernan and his Fender Baja Telecaster preach to the converted at Los Angeles’ Wiltern theater in October 2019. Photo by Debi Del Grande

What were you both listening to when writing these songs? There’s a lot of hip-hop and electronic-music flair on Ultra Mono. How does that stuff affect your approach to the guitar?

Kiernan: Andy Gill from Gang of Four is a big deal, but he didn’t come into my sphere of reference until I joined Idles. I love Gang of Four but writing parts like them wasn’t something I ever did until after the fact. Most of my guitar influence comes from Brian May, actually. Brian May is a god to me because everything he plays has feeling and purpose. Every solo he’s ever played was done with taste and style, every line he writes has a purpose within the song, and they’re warm and heartwarming. Even when he’s being technical, it’s never about showing off. It serves the song. Outside of guitar, hip-hop is obviously a big deal. I like to write parts by listening to Wu-Tang albums and playing along and seeing what comes from that, then applying it to what we do as a band. It’s got that bounce to it and it’s a feeling more than anything. You can hear that on this one in stuff like trying to make a guitar sound like the synth horn stabs from hip-hop records. The overall power of hip-hop records is a big thing for us.

Bowen: Andy Gill is definitely a big hero of mine, and influence, but I feel like his influence shows up more in Lee’s playing on this album. The main ones for me were all doom metal this time! It’s funny that we were borrowing that Sunn amp from Sunn O))), because in my head I was trying to get some of that band’s sound into our thing. I was thinking about the sounds of bands like Sunn O))), Electric Wizard, Sleep, and Earth. The idea I had was if Earth or Sleep played a hip-hop track. Also, a lot of my guitar sounds on Ultra Mono are going for mid-2000s French filter house and electro house ideas, like Ed Banger Records acts. There’s a producer called SebastiAn, and he has a song called “Motor” that sounds like a motorbike starting up, and it goes through various octaves and it’s such an incredibly direct sound. That was a driver for a lot of my sounds on this album. I really wanted a very direct, present-sounding guitar, and that’s where they start to sound like synthesizers, because oftentimes it’s hard to get guitars to sound that direct. Also, we saw the Hives play last year and that reignited my passion for that band and super-dry garage-rock sounds. “Ne Touche Pas Moi” was us trying to write a Hives song.

It can be really difficult to apply the weight and sub-frequency power of doom metal to a rock band’s sound and not come out the other side with watered-down death-metal riffs.

Bowen: It was really important for us for that not to happen. It was important that we got the rock side of things nailed, so the guitars aren’t trying too hard to sound like something from hip-hop, but it was through the way we mixed it and the production that Kenny Beats added to the rest of the track that we got that hip-hop flavor. If you look at the track “Grounds,” my guitar goes from being this completely inhuman, pitch-shifted delay sound that was meant to sound like a Daft Punk synth—it has a ring modulator on it and there’s the pitch-shifting delay—but it goes from that to a pure, almost AC/DC-ish guitar sound, the most human guitar sound possible. So it was about creating that dichotomy between sounds. I never want anything to detract from the central part, so on “Grounds” everything is bolstering that pitch-ascending distorted main riff. We needed the bass frequency of the track to be the main thing you felt, but we still needed to add a baritone guitar to it to get it where we needed it. We used a Fender Telecaster Bajo Sexto [30 1/4" scale] that belongs to the owner of La Frette. The thing just sounded fucking great and we ended up putting it on every single track. It was doing something in the bass region that a regular bass and regular guitar weren’t quite able to do.

Can you tell me about your relationship as co-guitarists and how you complement each other’s styles?

Kiernan: When we first started, we weren’t quite sure of what we were as a guitar team and we weren’t quite sure how to behave together, so there’d be a lot of playing over each other and clashing. We’ve started to settle into our own roles and now when someone writes something we like, we write around it and we feel off each other … rather than trying to play over each other. It took time to get that, and it took a lot of time to develop the consideration that goes with that. For instance, on “Grounds,” when Bowen’s playing that descending synth line, I’m playing a single almost empty note just to give his part that little extra sharp pluck at the beginning. That was done straight into the board with no effects, and it’s just a little extra rhythmic boost that isn’t a glory part, but it’s really important to the overall sound. That comes from understanding who we are within this band’s sound, and that each part has to have purpose within the song.

Guitars

2018 Fender Baja Telecaster with a Bare Knuckle ’68 Stagger bridge pickup wired direct to the volume pot

Amps

2003 Marshall 100-watt Super Lead plexi reissue

2000s Marshall JCM800 100-watt 2203

Two Marshall 2x12 cabs with Eminence Swamp Thangs

Marshall 4x12 cab with Celestion Creambacks

2019 Fender ’65 Twin Reverb reissue

1970s Peavey Pacer

Effects

The GigRig ABY-Baby

Moog Minifooger MF Chorus

EarthQuaker Devices Data Corrupter

EarthQuaker Devices Gray Channel

EarthQuaker Devices Arrows

EarthQuaker Devices Organizer Polyphonic Organ Emulator

EarthQuaker Devices Tone Job

Xotic EP Booster

Strymon Flint

Death By Audio Reverberation Machine

Death By Audio Robot

Death By Audio Micro Dream

Death By Audio Interstellar Overdriver Deluxe

Boss PS-6 Harmonist

Death By Audio Evil Filter

drolo Stamme[n]

Boss TU-3 Tuner

Boss EV-30 Dual Expression Pedal

Boss BD-2 Blues Driver

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Not Even Slinky (.012–.056)

Dunlop Tortex Standard 1.14 mm purple

Bowen: I would say that Lee is generally the trashier and brighter sound you hear, and I go for heavier and thicker sounds. When we play together, we kind of link up as one guitar. Whenever we play chord sections or parts that are the same, you really get a filling up of frequencies that sounds unique because those frequencies are being split between us. Lee’s really good at those stop/start parts and percussive sounds, and horrible, clashy reverberating sounds, and I do more of a Dick Dale, Link Wray, hold-the-fort kind of thing. On this album, we really got obsessed with each other’s sound and really got involved in how we could each complement that. I was focused on asking myself if I needed to play something specifically to complement Lee’s part or if I’d be better off laying back and bolstering the bass. It was really more about letting each other’s parts breathe and letting each other excel. We really worked together, and dynamically, on this one.

Ultra Mono has three producers: Nick Launay, Adam “Atom” Greenspan, and Kenny Beats. The band has worked with Launay on three albums now. What makes him the go-to guy for Idles? And what did Adam Greenspan and Kenny Beats bring to the table?

Kiernan: Adam Greenspan’s energy for getting weird sounds is great. For me, making noises is much more interesting than just playing guitar, and Adam is extremely enthusiastic about that process and his intrigue in it is huge. The post-production and mixing was a big, big part of this album.

Bowen: Nick Launay’s entire career has been about subverting what it is to make caustic, snarling rock ’n’ roll. If you look at his early stuff like the Birthday Party, Killing Joke, Gang of Four—he really coaches guitarists to not sound typical. Nick’s not afraid of sticking things up really loud and getting nasty. He just understands the post-punk ethos of subverting classic rock conceptually and taking things like surf-rock and making it completely different and weaponized. His understanding of guitars is something I love and that works really well with what we want to hear overall.

The mix on this album was so much of the trick, and we took four months to mix it. We had such a strong idea of what this album sounded like in our head. We were in the mixing stage and Nick and Adam had the guitars sewn up, but we really didn’t want to go through a traditional rock or post-punk mixing process. We wanted that hip-hop edge; we wanted the album to sound contemporary in a way that I feel Nick had some reservations about, because it had the potential to detract from the visceral, live-feeling energy of the band. Kenny Beats’ contributions to the drums and samples really helped us get that hip-hop power. When it really needs to sound like hip-hop, it does, but when you really need that caustic post-punk sound, it’s there as well. It was a real challenge and a group effort that I think took all of the producers out of their comfort zones, but it worked!

At last year’s Mercury Prize ceremony, Idles makes some noise for the proletariat, performing “Never Fight a Man with a Perm” from their short-listed Joy as an Act of Resistance. Catch the cascading waves of guitar throughout!

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)