(Originally published April 22, 2020)

At the dawn of the guitar-effects age, powering pedals was relatively simple. If an effects pedal didn't take a standard 9V battery like your AM transistor radio, it plugged into the wall like your avocado-green toaster. Forever dissatisfied, guitar players eventually grew weary of changing batteries, and plugging stuff into the wall was kind of a drag, too.

As the industry was looking to eliminate its batteries and Edison plugs, the effects purveyor Boss went a long way to standardizing pedal power by putting a 2.1 mm coaxial power jack on all their pedals, and while their market dominance made the 1/8" jack on certain Ibanez and Pro Co pedals outliers, even they couldn't stick to one standard for long as they transitioned from 12V ACA spec pedals to 9V PSA spec pedals.

Once that growing pain subsided, it was relatively peaceful on the pedal-powering front for many years, and the standardization allowed companies to produce power supplies that let players power all their pedals simultaneously and without harming a single battery. Some supplies had a single output with daisy chains to fan out power to multiple pedals. Some were isolated, offering an individual power port for each pedal and eliminating daisy-chaining all pedals in a parallel fashion. Isolated supplies were a huge development in pedal-powering history, so let's dig in there before wading further into the power morass of today.

In this context, isolated power supplies are those supplies that are essentially a series of separate power sources in one enclosure. Each supply stands on its own with no direct connection to any of the other supplies, and, as such, the effects they power have no direct connection to one another through their respective power ports.

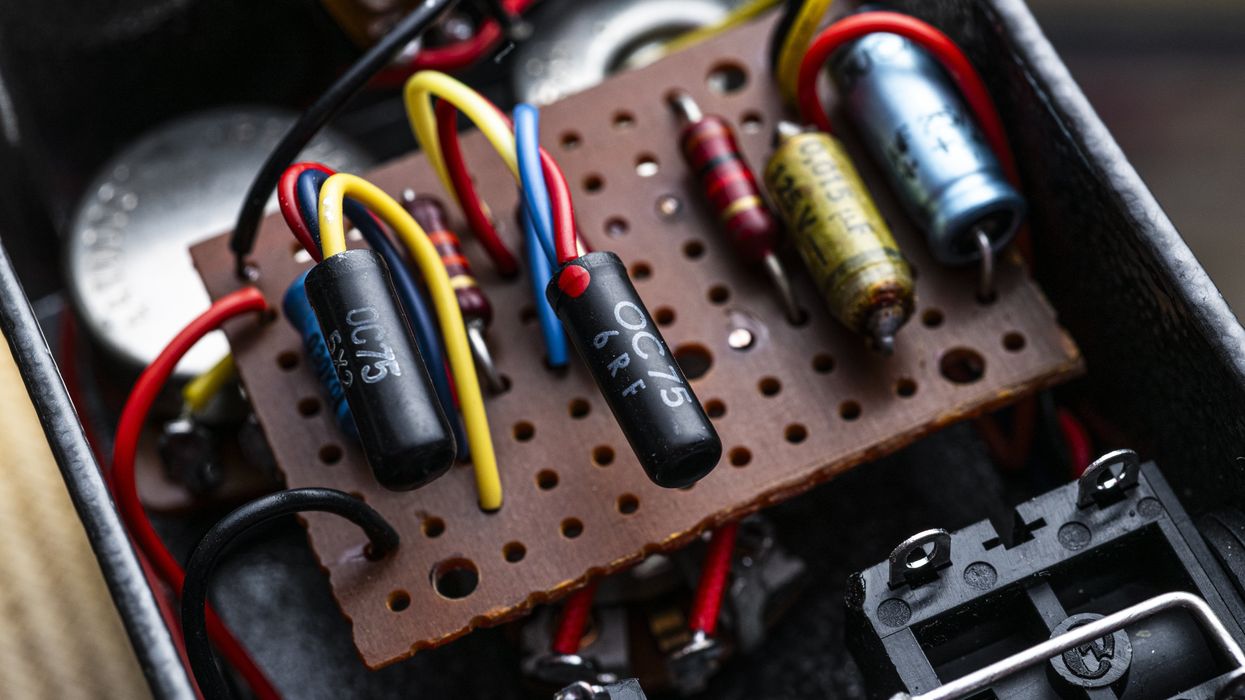

There are several reasons power supply isolation can be anything from favorable to crucial. First, some pedals have a positive-ground scheme, where the audio ground of the effect is connected to the positive terminal of the battery, usually due to the type of transistors used in the pedal's circuit.

Isolated power supplies are those supplies that are essentially a series of separate power sources in one enclosure.

While fuzz pedals are often set up this way, most pedals have a more conventional negative-ground scheme. If you parallel connect the power of a positive-ground pedal to a negative-ground pedal, and then connect their audio grounds together with a patch cable, you'll cause a power supply short, and neither pedal will get power. The power source will complain, too! Isolated supplies mimic a battery as each device gets its very own power source to use independently of any other device.

Crosstalk is another reason for isolation. Some pedals don't play well with others when powered in parallel. Like so many playground bullies, tremolos and vibratos can tick and pop while overdrives and DSP effects with switch-mode supplies and high-speed processors can whine, and they can torment their boardmates with their glitches. These deficiencies might not bother the offending pedal, but the trash they put on their power supply ports gets leaked to other connected devices that may not be able to reject the noise quite as well. Isolation breaks the link and prevents such crosstalk.

The last reason for isolation we'll list here is ground loops. In general, for guitar rigs, it's best practice to have just one ground path. Typically, that one path should be the ground connections of all of your patch cables extending in a line from guitar's output to amp's input. Daisy-chaining power creates other ground paths that make closed loops from one section of your signal flow to another. These ground loops can make your rig more susceptible to hum pickup in the presence of electro-magnetic fields. If you have daisy-chained pedals both in front of an amp and in its FX loop, and dozens of feet of cable between them, the associated ground loops can become very large and produce a great deal of noise. Using an isolated supply disconnects the links that make the loop, and the induced hum can no longer be sustained.

With isolation addressed, power supplies remained relatively unchanged for many years. Then, digital-signal processing became cost-feasible for common use in guitar-pedal effects. We'll dig further into their high-current demands and how they've complicated the power supply marketplace in my next column.