Not long ago, guitar pedals were made by larger companies with the machinery, infrastructure, distribution networks, and resources to bring them to market. The big players were names you know—like Boss, MXR, Ibanez, Electro-Harmonix, and others—plus a handful of outlier operations, and that was about it.

But guitarists like to tinker, and a lot of players took their devices apart, modified the circuits, improved designs, and conjured up innovative ways to craft tones. But tweaking pedals, or even developing new ones, is a far cry from launching a pedal company, and most aspiring builders did not have the wherewithal, or desire, to do that. Even for hobbyists, information was hard to come by. Schematics were difficult to find, and mentors—or even just brains to pick—were few and far between. Taking those factors into account, the idea of a boutique pedal scene was beyond most people's imagination.

Then something wonderful happened. Although books and articles about simple electronics projects for musicians had been circulating since the early 1970s, putting that information online helped spawn a pedal-making revolution. Schematics, definitions of terms, innovative insights and tweaks, and easy access to experts to consult when you got stuck became commonplace.

And as the internet developed, that only got better. Rare, impossible-to-find components were unearthed or reissued, and the ability to find buyers, seemingly everywhere, made it possible for anyone with a workbench and a dream to get in on the act. The prospective builder could build pedals at home, produce them one at a time, and find a market no matter how niche. And with that, the boutique pedal community was born.

Today, thousands of pedal companies compete and thrive in a space once dominated by a few, and their offerings—from thousands and thousands of variant fuzz circuits to oddball mutant glitchy delays—exist in excess. Even crazier, they all seem to make money.

To tell the story about how this scene developed, we spoke to the people at the heart of the movement. That includes Craig Anderton, the godfather of the scene; R.G. Keen, an innovative engineer, forum regular, and founder of the GEO website (Guitar Effects Only, geofex.com); early boutique pioneer and pedal information guru Analog Mike Piera; Aron Nelson, the founder of DIY Stompboxes, which is one of the oldest and most influential online forums; musician, audio developer, and guitar gadget expert and builder Joe Gore (also a contributing editor at Premier Guitar); and boutique legend and builder Robert Keeley.

On the surface, the birth of the boutique pedal scene is a story of changing technology, but, really, it's a story about community. It's about people working together, sharing, volunteering, and offering support, which, in these hyper-politicized, polarized, strange times, is a wonderful thing.

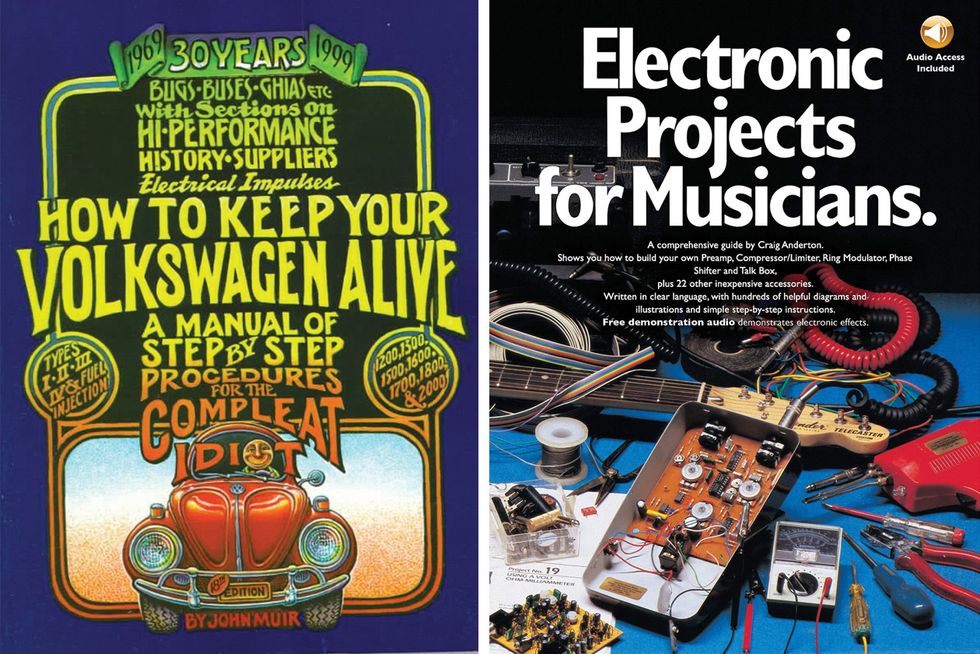

Craig Anderton used a car manual, How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive (left), as a template for writing his guitar-tech opus, Electronic Projects for Musicians (right). The book by Craig Anderton came out in 1975 and was like a guitarist's bible for understanding tech aspects of gear. Anderton is currently working on his 45th book.

How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive

Craig Anderton gets the credit as the person who brought pedal building to the masses. “Reverb did an interview with me at NAMM," he says. “They were doing something about the history of pedals, and they said that half the companies they spoke to got started with my book [laughs], so they figured they better talk to me."

Anderton's book Electronic Projects for Musicians was first published in 1975, and that, as well as his monthly column in Guitar Player magazine, demystified the insides of music technology and inspired people to look under the hood. It gave hobbyists a green light to tinker, and even inspired budding engineers.

“I was heavily into Craig Anderton's series in Guitar Player," says R.G. Keen, whose GEO site also had a major impact on the early boutique scene. “He was a major influence. I learned and tinkered with his very early stuff. I was already headed for an engineering education, and it got me started on the road of electrical engineering."

Anderton is a guitarist and received some notoriety with his late-'60s band, Mandrake Memorial, touring parts of the U.S. and England and opening for acts like the Doors and Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. He started writing about DIY projects for musicians in Popular Electronics magazine in 1968. By the mid 1970s, Popular Electronics switched its focus to computers and stopped publishing music-related projects. Anderton, looking for work as a writer, reached out to Guitar Player.

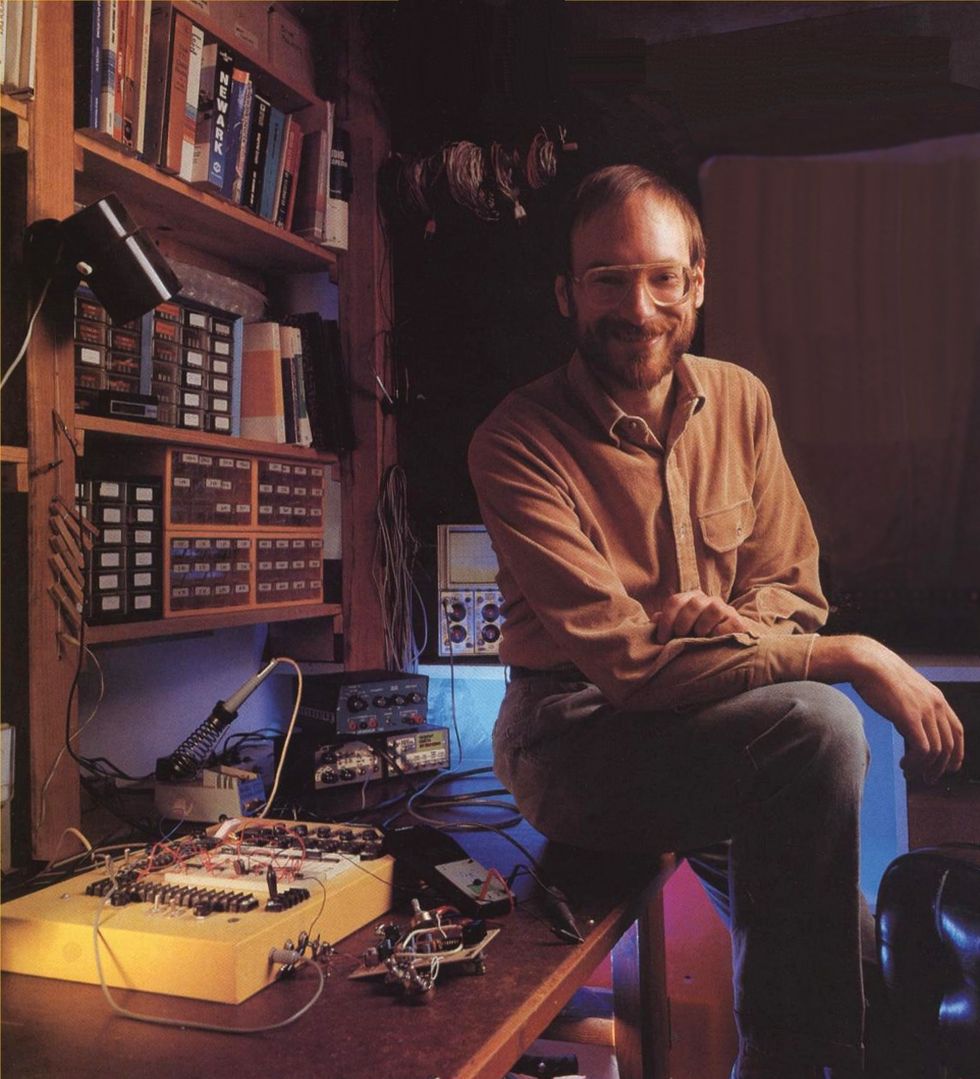

Craig Anderton, a godfather of pedal building, began writing for Popular Mechanics in 1968, and then started a monthly DIY column in Guitar Player in the 1970s.

“I pitched them on doing an article about a headphone amp, but they had a couple reservations," he says. “One was, they didn't think anybody cared, and two, they were afraid that someone would electrocute himself. Apparently, they had done an article on an amp modification, and someone almost electrocuted himself. Eventually, they asked someone at Alembic about my circuit. Alembic said it was safe, and I sent Guitar Player the article, but they wouldn't let me do the schematic. They said, 'No, we have our own art department and our own look. We'll do the schematic.' I said, 'But if you make a mistake, the thing won't work.' They said, 'We'll get it right. It will be perfect.' Well, they made a mistake on the schematic, and the thing couldn't work. You would think it would be a disaster, but I owe my current level of success to that art department making a mistake. They got over 300 letters from people that varied from, 'Gee, I never built anything before, so I must have done something wrong,' to “Hi, I'm an audio engineer at National Semiconductor and you know there is a mistake in the schematic.' They decided there must be interest in this stuff. They asked me to write another article, which was the treble booster, and that evolved into the column, which evolved into Electronic Projects for Musicians."

Anderton is currently working on his 45th book, but in 1975 he was a beginner and unsure what to do. Inspired by the handbook, How To Keep Your Volkswagen Alive, by John Muir and Tosh Gregg, which he used to keep his 1966 Volkswagen running, he borrowed the book's format as the template for his fledgling release.

“How To Keep Your Volkswagen Alive assumed you knew nothing—and I mean nothing—and I was able to do all kinds of things to my car thanks to that book," he says. “I realized that book was the outline I needed to follow for Electronic Projects. The first thing it did was discuss the terms you needed to use, and then the tools, and then the techniques involving those tools, and then the actual projects themselves, and then what to do if something went wrong. I followed that outline and did the book, and it did really well."

Analog Man Mike Piera was a software engineer working for a Japanese company in the early '90s when he started tinkering with pedals. “I started out doing the Tube Screamer mods, because you couldn't find 808s back then," he says.

Pedal Modding Begins

Anderton's book opened a door and gave musical laymen—people who didn't work for major music equipment manufacturers—projects to try, and, more importantly, permission to experiment. But if you got stuck—and you didn't have Anderton's phone number or physical mailing address—you were stuck.

The internet changed that. Even before the development of the World Wide Web, the nascent internet made it possible for aspiring new builders, often working in isolation, to find like-minded enthusiasts, share information, ask questions, confer with experts, and eventually even check out schematics of classic devices.

The earliest groups were user networks, or Usenet groups, and email lists. Although at that time computers were not yet ubiquitous, and only real nerds—engineers, and others working in the tech field or somehow associated with a larger institution—had access.

“In the early days of the internet, people didn't have computers, there were no cell phones, and pretty much the only people on it were engineers and scientists," says Mike Piera, who started his pedal company, Analog Man, in those early years. Piera was a software engineer, worked for a Japanese company, and split his time between the U.S. and Japan. During his downtime in Japan, he discovered the vintage guitar market, which, eventually, piqued his interest in vintage pedals. “We just had email back then, and some forums. Usenet, before there was a World Wide Web, was the way you interacted with people. You would post something, and it was like a forum. Most of it was probably used for porn and weird things. There were a lot of 'alt' things—'alt' meant like alternate lifestyles. The guitar effects forum was alt.guitar.effects, or something like that, because it wasn't totally mainstream. People like R.G. Keen, Jack Orman, and a lot of guys were on that forum helping each other out."

Piera got his start on those early forums. Web pages didn't exist yet, and he had a large file on his desktop filled with cut-and-paste replies—so he didn't have to retype the same instructions over and over again. His first project was modding Ibanez Tube Screamers. It sold well, and that's how he got out of software engineering and full-time into pedals.

Mike Piera's Tube Screamer mods caught on in the 1990s through Usenet forums. Guitarists would send Piera their pedals to mod, along with a payment, and a business was born.

“I started out doing the Tube Screamer mods, because you couldn't find 808s back then," he says. “This was in the early '90s, and I figured out how to mod the 9s into 808s. I mentioned [on one of the forums] that I modified Tube Screamers with parts I got in Japan. People would post things like, 'Can I send you mine, and you'll mod it?' I came up with the mod to make it public, and a lot of people were sending their pedals in. I was really surprised that people would just send me their pedal and money and expect to get it back. But once I started doing a few and people were raving about them, then the orders kept coming in."

Godfathers of the Gear Forums

As the internet developed, and the World Wide Web became a thing, it became possible—despite slow speeds and painful dial-up connections—to post content on actual web pages. Some of the people to take advantage of that included bona fide electrical engineers, like R.G. Keen, who was based in Austin, Texas.

Keen worked for 30-plus years at IBM. He was with the company as the personal computer movement started to develop, took an interest in the possibilities that meant for music, and was an early adopter of the IBM PC serial adapter card, which was converted over to run MIDI. He was also interested in music-related electronics—like guitar pedals—and joined the online chatter early on. In addition to his contributions to many forums and conversations, he launched his own site, GEO FX, which is a repository of insights and wisdom.

R.G. Keen points to the Internet for the rise in pedal enthusiasts. “It snowballed. It was the availability of the information—because we have the same number of people these days who are interested in doing technical and musical stuff—but before the Internet, they didn't have a way to express that. I think of the soldiering iron as a tool of expression, just like a guitar is."

“The wider internet that existed in something like today's form only started in the mid-to-late '90s, roughly the same time we were getting started," Keen says. “I wound up with a local internet account from a provider here in the Austin area—eden.com [The site today is for UNICOM Global, which looks like a software company.]—and I did the earliest work on GEO FX in late '97. A year or two later, I was regularly turning out articles and putting them on GEO FX, and I had that name for it by then."

“I view that site as a little bit of paying it forward or paying it back," he continues. “I used GEO FX as a way to tell other people, 'Here is how you can do more advanced stuff in electronics. Here's how you make more guitar pedals.' I viewed it as ways people could think about the electronics in ways that maybe would help them. There is a lot of stuff on GEO FX that is purely, 'Here's a technique,' or 'Here's how it's done.' I went through a period there in the late '90s and early 2000s where I was thinking about getting into the business of selling guitar pedal kits and electronics. I started on that a little bit, and said, 'Nah, let's just do the intellectual stuff. I can tell people that this is a schematic. This is how to put stuff together. Here's a trick on how to drill your boxes so that everything fits.' That's really what GEO FX evolved into."

But more important than Usenet groups, email lists, and even information-laden websites—like Keen's site, General Guitar Gadgets, Harmony Central, and online pedal guru, Jack Orman's site, AMZ (at muzique.com)—were online forums. The forums were, and still are, places to have open discussions about problems, learn new tricks, and interact with experts and others with more experience. One important forum, first launched in 1999 by Hawaii native Aron Nelson, is DIY Stompboxes.

“What I'm most proud about is that on my forum, there's hardly any fighting," says Aron Nelson. "I don't like fights, and I try to get people, for better or worse, to be civil. I realized that I have these genius guys, like R.G. Keen, Mark Hammer, and others, and they are helping people out night and day. People appreciate that. It is just a great place to be."

“It was a fantastic time at the beginning," Nelson says. “Jack Orman and R.G. Keen were almost like the godfathers of this whole thing. Jack with his page, and R.G.'s, and they are still helping people now. Another page was ampage.org, and that was actually one of the biggest forums around—today it goes under the name Music Electronics Forum—and at some point they even hosted a subsection for me, because I was totally into it. It was guys like me who were having fun making these things. It felt good. But then there were the other guys who were figuring out how to monetize it. For me, it was a total hobby. I thought, 'If I can make these things, I'm going to get other people to realize that they can make their own effects, too.' That was my goal. The beauty of building your own—or at least knowing how to modify it—is that you can get it that much closer to what you want. And that brings up another point, too: Most of the people on the forums are not electrical engineers."

“DIY Stompboxes was really the first good place on the internet, after Usenet, and more specifically to the DIY aspect," Piera says. “On Harmony Central, if someone asked, 'Can somebody help me? My Tube Screamer died,' the reply would usually be, 'Go to DIY Stompboxes and search it.' He was definitely about building, repairing, and stuff like that. It was a really good forum, with lots of good people, and not too many idiots on there—very little as far as shills or snake-oil salesmen. I still send people there, and I still check it out every few months or so."

Guitarist and gear guru Joe Gore got his start in pedal building by asking questions on forums like freestompboxes.org.

Murky Waters

That said, the online forums were not without controversy. Some builders were unhappy when their schematics were posted online, and spoke up, both online—delineating the real costs those posts had on their income—as well as to the site moderators. Others disagreed, and felt it was an issue of censorship, which led to new forums, like freestompboxes.org, that took a different approach.

“While everybody enjoyed sharing circuits, there were a number of people who didn't like the fact that their circuits got commercialized," Nelson says. “Some of them would write me and beg me not to have it published. One guy wrote me directly and asked, 'Please don't post this schematic.' A lot of people didn't agree and saw it as censorship. Other forums came about where they didn't want any kind of censorship happening. But the way it was worded was like, 'This is my livelihood. I feed my family with this.' What am I supposed to say? I'm a musician. I can totally see that."

Joe Gore, who has a deep resume in digital audio design as well as his own line of analog pedals, got his start asking questions on online forums, particularly freestompboxes.org. He's also, in addition to being an in-demand guitarist (Tom Waits, PJ Harvey, Tracy Chapman), a contributing editor at Premier Guitar. He says some pedal builders were very reluctant about schematic sharing. “One very influential builder I will not name, but who I admire immensely, was particularly active in trying to squash this sort of activity. It's someone I look up to, and who has done far more for the field than I'll ever do, but I don't agree with his point of view. By and large, trying to contain information tends to be a losing battle. That argument can be reduced to absurdity, but more often than not, I think the free exchange of ideas is a good thing."

A bigger issue is theft. Theft might not be the right word, because, at least according to the tight, nuanced language of copyright law, it's not possible to copyright a schematic, but ethical issues abound. One issue is cloning, which is controversial, but accepted as part of the culture. Another, which crosses a line, is taking designs and marketing them as your own.

“What is less cool is when a large player comes in and plays copycat," Gore says. “The most notorious example was Danelectro. About a dozen years ago, they came out with a line of pedals. Participants in the DIY forums realized very quickly that they had very literally gone through and picked a half dozen of the most popular boutique pedals and copied them. One of them was the Paul Cochrane Timmy, Frantone was another—she [builder Fran Blanche] is one of the few women builders, out of Brooklyn. They came, lifted everyone's creativity, and made cheaper pedals that were exact look-alike, soundalikes, and got called out in the community. Danelectro initially denied it, then they copped to it and apologized. I don't think these pedals are in production anymore."

According to Piera, it's also important to note that not every suggestion posted in an online forum is a revelatory insight that's going to improve your sound. “One thing I noticed," he says, “is a lot of times you'll read articles about a modification, how it's easy and great, and then you do it and there is nothing there. The point is about the technical aspect rather than the actual sound. It sounds great in theory, but you try it and it doesn't really work. It's not that useable, and there is a lot of stuff like that."

eBay Points the Way

Aside from access to information and resources, the primary barrier to bringing pedals to market was sales. If you made a pedal in your basement, even if it was great, where were you going to sell it? Setting up distribution channels was challenging, but even if you did that, how did you keep up with demand making one-offs in your basement? For many builders, selling pedals on consignment at the local music store also wasn't an attractive option.

But sales via web, first with the ability to reach a large audience of like-minded people via Usenet groups, email lists, and dedicated websites, followed by the rise of online marketplaces like eBay, changed everything. It leveled the playing field and allowed businesses—even loners hand-soldering pedals in their kitchens—access to customers. But bigger than that, and what no one expected, was that demand was, and still is, incredible.

“I was teaching at a tech school, a little private college, and I decided to list one of these compressors that I built on eBay, and it sold instantly," pedal builder Robert Keeley says about the start of his company, Keeley Electronics.

“I was teaching at a tech school, a little private college, and I decided to list one of these compressors that I built on eBay, and it sold instantly," pedal builder Robert Keeley says about the start of his company, Keeley Electronics. “I put another one up there, and I said it's going to be a four-to-six week wait, and it sold instantly, too. I put another one up there, and said it's going to be a six-to-eight week wait. Eventually, it was 10-12 weeks. People would click, and buy, all day long."

“Robert Keeley jumped directly onto eBay and sold a million things there," Piera says. “But they take a lot of your profits, so I never did that. I still don't do eBay. I sell more than enough stuff without having to give a percent of my profits away to eBay, although the market on eBay is huge, but I just never needed it. But after Usenet, eBay didn't really come out until after you had websites."

Another important innovation is mass customization. Mass customization is a manufacturing technique, similar to, say, printing books on-demand, or one-off pressings of T-shirts and coffee mugs, except applied to more complex products, like circuit boards. That level of hyper-customization made it possible for pedal builders to up their game and produce small runs of quirky, glitchy, niche devices. It's a technique that was unheard of in yesteryear—especially at a time when hand-soldered, through-hole circuits were the only option—but that, coupled with the ability to order online and import from overseas, changed the game yet again.

“It's not hard to get circuit boards made," Anderton says. “You can get a couple hundred made in India or China for pretty cheap and they're not big to ship or anything. [It used to be] more complicated, because the circuit boards had to all be laid out by hand using tap and dots and things like that, and measuring them was difficult. Nowadays, you can whip the stuff off on computers in a few minutes and send it off to get a bunch made."

These changes in manufacturing have also made it possible for companies to reissue discontinued transistors and have made once hard-to-find electronic components accessible and affordable.

“Electronics have become very cheap, and the parts are mightily available," Keen says. “That was not true all the way up into the late 1980s. You could actually find electronics parts, but it was difficult. You had to buy them at quite high prices from the few places that sold transistors. Places that sold electronic wiring for an integrated circuit … there were very few of those. Today, you can find them everywhere through the internet. The effective price has gone down tremendously."

Needless to say, with changes in technology and access to virtually everything, relying on large corporations for things like effects pedals is so 20th century. The internet may be a cesspool of hot takes and snark, but it gave wannabe pedal builders access to information, and experts to consult when they ran into snags. It also gave them a platform to sell their wares, cheap access to electronic components, and an opportunity to compete in the big leagues.

But better, pedals were the perfect product to spawn a boutique revolution. They don't require advanced artisan skills like lutherie, and unlike building amplifiers, which operate at high voltages, they're relatively harmless. If you have a soldering iron, a handful of transistors, good ideas, and a can-do attitude, the world is your oyster.

“The beauty of pedals is that they're easy to work on and safe," Nelson says. “You're not going to get killed using a 9V battery. The empowerment of knowing you can swap a few capacitors and make a pedal sound twice as good—knowing that you can do that and you don't have to be an electrical engineer—and the fact that you can go and ask questions, pretty much empowers everyone. You can make anything you want within reason."

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)