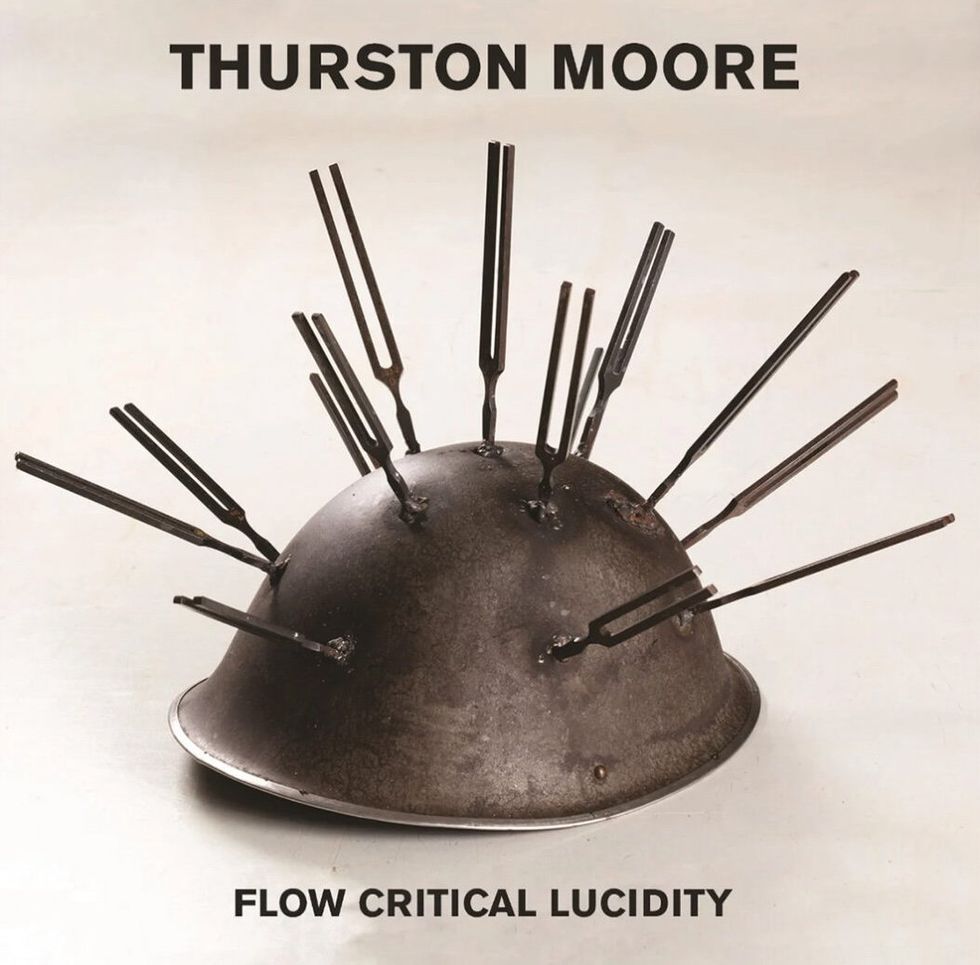

On the cover of Thurston Moore’s new solo effort, Flow Critical Lucidity, sits a lone metal soldier’s helmet, spiked with an array of tuning forks jutting out in all different directions. The image, a piece from the artist Jamie Nares titled “Samurai Walkman,” seemed to Moore an apt musical descriptor of the record.

“There’s something very elegant to it—the fact that the helmet sort of denotes a sense of military perfection, but that it has tuning forks on it as opposed to any sort of emblem of aggression,” he tells me, Zooming in from his flat in London. “If music is, as Albert Ayler would say, the healing force of the universe, then so is the tuning fork. I thought it was just a thing of beauty.”

It also dovetails with a theme that runs through Flow Critical Lucidity, an album that Moore describes as “an expression of hope.” But characteristic of the Sonic Youth guitar icon, there are additional layers at work here. One would be that Nares is, like Moore, an alumnus of the downtown Manhattan no-wave scene, having played guitar in an early iteration of James Chance and the Contortions. “It felt right to use one of Jamie’s pieces, because we kind of came up together through this musical micro-community in New York City,” Moore says.

Another layer, I suggest, might be that the many tuning forks are a self-referential poke at Moore himself, who has made something of a career out of deploying myriad out-there tunings in the service of some of the most innovative and influential music of the past 40 years. “So, they’re ‘alternative-tuning tuning forks,’” Moore reasons, then smiles. “Maybe I could have written C–G–D–G–C–D on it.” Which is, in fact, the actual primary tuning he employed for his guitar parts throughout Flow Critical Lucidity.

Why this tuning? “I like it,” Moore says, simply. “I find it to be a good one to write in, and I’ve gotten used to it. So it’s been a mainstay for the last six years or so, and on the last couple of albums. I actually feel like I need to put it to rest a bit, because that low string tends to create this kind of droning low C on almost every song now. Maybe I’m getting a little too comfortable.”

You wouldn’t know it from Flow Critical Lucidity. Moore’s ninth solo album overall, the collection is an enchanting, transportive, and deeply creative work: There’s cadenced spoken word over clanging, chiming soundscapes on “New in Town”; gorgeous guitar and piano commingling in “Sans Limites” (with Stereolab’s Laetitia Sadier dueting on vocals); feral, percussion-heavy rhythms pulsing through “Rewilding”; a no-wave callback in the jagged four-note guitar stab of “Shadow”; hypnotic, liquid guitar lines punctuating “The Diver.” There are electronics courtesy of Negativland’s Jon Leidecker, lyrics penned largely by Moore’s wife and collaborator, Eva Prinz (working under the pseudonym Radieux Radio), and, on several tracks, extensive use of prepared instruments, such as guitars with objects placed under or on the strings to modulate their tone. It is an album that is varied and vibrant, imaginative and idiosyncratic. It is, Moore has said, one of his “favorite” records in his solo catalog.

On Flow Critical Lucidity, Moore recorded with guitarist James Sedwards, bassist Deb Googe, keyboardist Jon Leidecker, and percussionist Jem Doulton. The record was mixed by Margo Broom.

“If music is the healing force of the universe, then so is the tuning fork. I thought it was just a thing of beauty.”

Though somewhat sprawling in execution, Flow Critical Lucidity came together in a uniquely focused manner, with Moore and Prinz settled at an artist residency near Lake Geneva. “They allow people to stay there for six weeks to six months to sometimes a couple years,” Moore says. “So I asked if I could lock myself away there and write—and specifically to write a new record. I had a couple guitars, a couple small amps, and a little Zoom digital recorder. Eva would throw lyrics in front of me and I would construct pieces around them.”

When it came time to record, Moore assembled his current band—Leidecker, former My Bloody Valentine bassist Deb Googe, guitarist and multi-instrumentalist James Sedwards, and percussionist Jem Doulton—at Total Refreshment Centre (“a funky little studio”) in his adopted home city of London. A key architect at this stage was Margo Broom, who mixed the material. “She was really able to put it in a place that I don’t think anybody else could have so successfully,” Moore says. “For instance, while she was mixing, I was talking to her about how to treat my vocals a bit, because I never liked my vocals so much—I’m kind of key-challenged when I sing. But Margo was able to finesse that. She said to me, ‘I’ve been listening to your vocals since I was 16 years old, so I know what I’m doing here!’ I was impressed by that.”

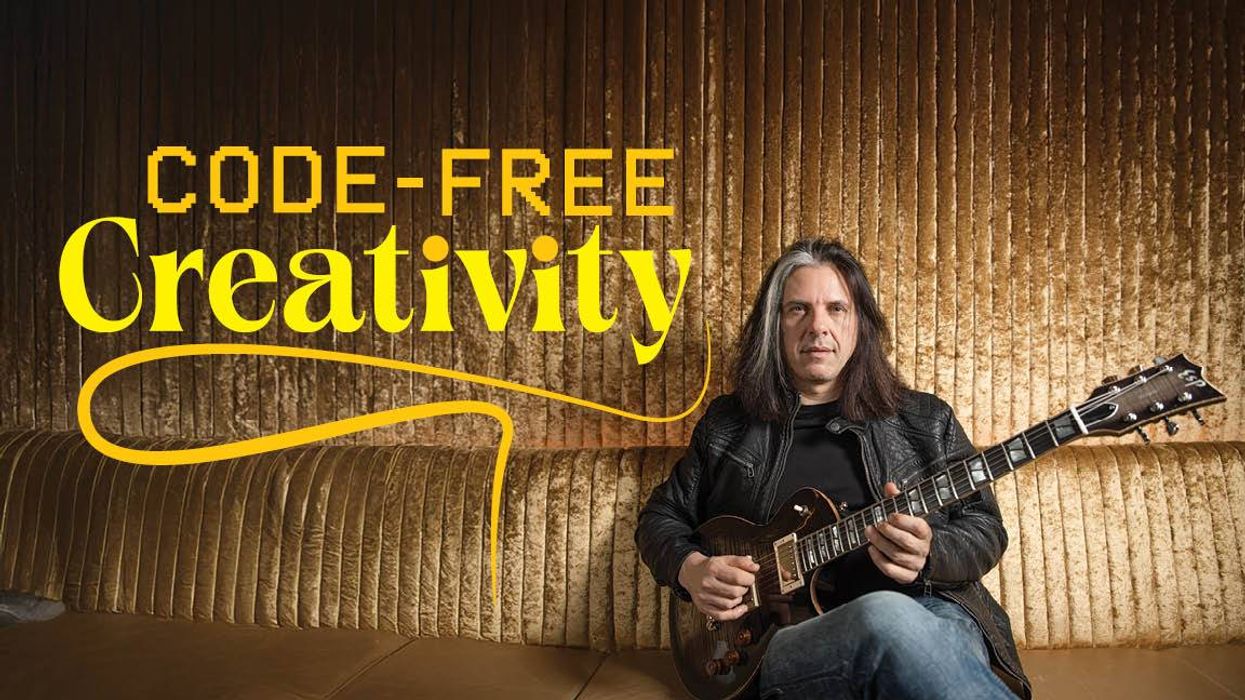

Moore, now 66, often records with his tried-and-true alternate tuning, C–G–D–G–C–D.

Guitar-wise, Moore continues, “Margo was able to create a lot of space, which is something that I’ve never really felt has happened so successfully, even all through Sonic Youth, because of the desire to always have a lot of guitar layers happening in the songs. But she was able to find definition there, even where there was a lot of mass information going on.”

To be sure, there’s plenty of characteristic Moore guitar work on Flow Critical Lucidity, particularly in the extended instrumental sections of songs like “The Diver” and the gently chugging “Hypnogram.” But as far as the actual gear he used in the studio, Moore kept things streamlined—one guitar, one amp.

“It was all Fender,” he says. “I used an early, pre-CBS Jazzmaster, a ’62, I think, and a Hot Rod DeVille.” Moore is, of course, a longtime Jazzmaster aficionado—in the early days of Sonic Youth, he says, “We started acquiring Jazzmasters before they became so collectible. You could go to the guitar stores in midtown New York and find one for a few hundred dollars. We had been using Harmonys and Kents and Hagstroms—whatever we could get our hands on—and the Jazzmasters and Jaguars were a step up. I gravitated more towards the Jazzmaster because the neck was slightly longer than a Jaguar’s, and for my height it worked nicely. I also liked other aspects of it, like being able to investigate behind the bridge more readily than with just about any other guitar.”

“I had a couple guitars, a couple small amps, and a little Zoom digital recorder. Eva would throw lyrics in front of me and I would construct pieces around them.”

Moore has many Jazzmasters, including one that he says is “one of the first ’58 production models,” and that Sedwards has been using extensively. But the Jazzmaster that Moore is playing now “has been my go-to for the last couple of albums. And a lot of that was defined by the one I played previously getting stolen. And then one previous to that getting stolen, too. So the record is all this guitar, and it’s all, I believe, in that same [C–G–D–G–C–D] tuning.”

Thurston Moore's Gear

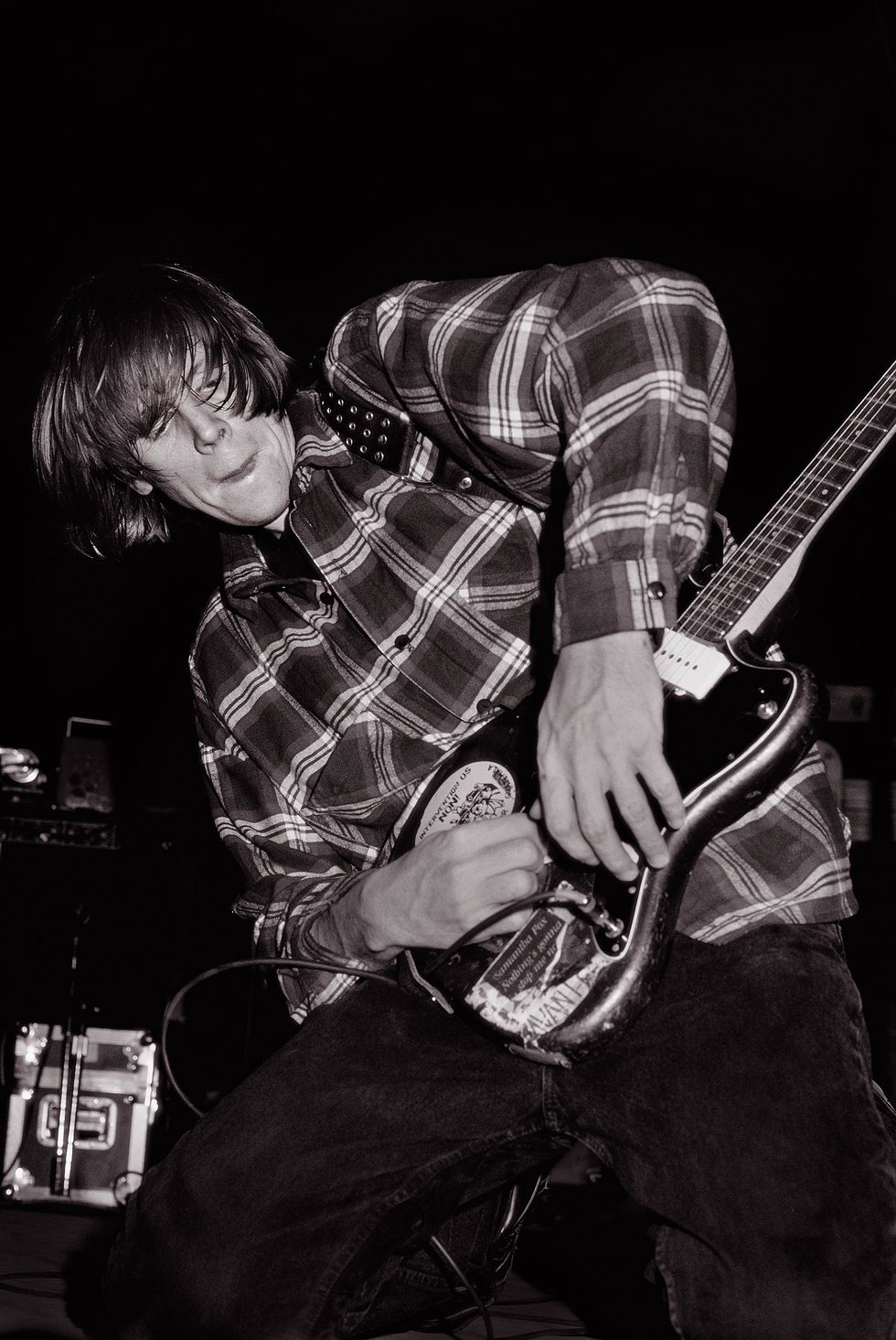

Moore became famous as co-guitarist and one of three vocalists in Sonic Youth, seen here performing in 1991.

Photo by Ken Settle

Guitars

- Circa 1962 Fender Jazzmaster, tuned to C–G–D–G–C–D

- Circa 1958 Fender Jazzmaster (used by James Sedwards)

Amps

- Fender Hot Rod DeVille 410 III

Effects

- Pro Co Turbo RAT

- Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Octave Fuzz

- Xotic EP Booster

- Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff

- Electro-Harmonix Cathedral Stereo Reverb

- TC Electronic Hall of Fame

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario NYXL (.012–.054)

- Dunlop .60 mm

Except for one song, that is. “‘New in Town’—I couldn’t even tell you what the tuning is,” Moore admits. “That song will not be played live, because it just can’t be.” The reason why, he explains, is that he performed it on prepared guitar, altering the Jazzmaster’s sound by placing objects under or between the strings and retuning the instrument in real time.

“The idea of using guitars that are extended with different implements is something that obviously I’ve been working with since the early ’80s,” he says. “But ‘New in Town’ was probably the most expansive effort of it in terms of creating a song where the preparation of the guitar was in a place of improvisation while we were recording. On that song, I’m actually moving the strings around with the tuning pegs to a point where I’m not really notating what I’m doing, and I’m furthering that by putting different implements between the strings—not just under the strings and in front of the fretboard, but actually sort of woven within the strings. Like, maybe sort of midway on the neck and then over the pickup area, and then playing in the middle between the two.”

“I never liked my vocals so much—I’m kind of key-challenged when I sing. But Margo [Broom] was able to finesse that.”

Some of the types of objects he used were “a small, cylindrical antenna; a drumstick,” Moore continues. “And then I’m picking between those two, or on either side of them, and finding a rhythm or a motif. And I’m doing this while James is playing piano and Jon is processing it and moving it around through his electronics. We recorded that, and then I took it and I cut it up and edited it to create the composition. So the actual performance—I don’t think I’d be able to reenact it again.”

For Moore, the structuring of the track was as much a creatively fulfilling endeavor as the actual performance of it. “I find that, for me, a lot of the experimentation that has rigor is in that part of it, rather than in the expanded technique on the guitar,” he says. “I feel like that’s something anybody can do, and that a lot of people do do. I mean, when I was younger and I brought the drumstick out, and I was swiping it across the strings, and it’s going through a distortion box, it sounded really cool, but it also looked really cool. I knew that there was something very performative about it. But the composition has to have value beyond the oddity of what you’re doing.”

“That song will not be played live, because it just can’t be.”

He laughs. “You know, I’ve seen comments on social media, like, ‘Playing guitar with drumsticks is stupid!’ Which I thought was a really great comment. Somebody was just not down with the program on that one. I was like, ‘Right on!’”

Which brings up a question: Does Moore immerse himself at all in the online guitar world? Is he, like the rest of us, endlessly scrolling through 30-second clips of bedroom guitarists performing jaw-dropping feats of 6-string technical facility?

The answer is, sort of.

After producing several albums with Sonic Youth, Moore began releasing solo works in 1995 with Psychic Hearts. This photo was taken in 2010.

Photo by Mike White

“I’m in that algorithm, so I will get these interesting tutorials from, like, hyper-tapping kinds of players,” he says. “And I will sometimes watch them, because I’m actually very enamored with high-technique guitar players. Even though I don’t really consider myself a high-technique guitar player—I find myself to be a very personalized-technique guitar player. And I’m okay with that.

“But I do like it,” he continues. “Whether it’s Hendrix or some guy sitting on his bed and shredding. Or someone in front of their laptop decoding a Zeppelin thing, like, ‘This is how you play “Misty Mountain Hop” correctly.’ To me that’s really interesting to see, because I love Jimmy Page. I’m never going to play like Jimmy Page, but to have someone decode it and then share that with the world, it’s like, ‘Thank you.’ If I had more time on my hands, I would tune a guitar to traditional tuning and sit down and learn it.”

“I knew that there was something very performative about it. But the composition has to have value beyond the oddity of what you’re doing.”

Most people, of course, don’t usually have to first retune their guitar to standard before they play. But then, Moore is not most people. “I don’t think I have a single guitar in that tuning,” he admits. “And it’s funny, because [Dinosaur Jr. singer and guitarist] J Mascis used to come over, and he’d tune all my guitars to traditional tuning. And it was like, ‘Stop doing that!’ you know? Would drive me crazy.”

At the end of the day, Moore’s intention is to remain creatively open. Even while he is in the throes of the album cycle around Flow Critical Lucidity—“I’m still coming to terms with what we did on this record,” he says—he’s already looking forward to what might be next. “I have it in mind, but I couldn’t say what it is. Sometimes I think I want to make a brutal, harsh, noise-wall record. Or maybe something that’s a super, super-dark metal record. Because I love that kind of stuff.”

There’s still a lot of ground, and music, to explore. “It’s all live and learn,” Moore says. “Even at 66 years old, I still feel like I’m in some place of apprenticeship with a lot of this. I don’t really feel settled. But I do feel more confident, that’s for sure.”

YouTube It

Thurston Moore, with Jazzmaster and Hot Rod DeVille, performs the Flow Critical Lucidity track “Hypnogram” live in Munich in 2023 in this fan-captured DIY video.