Of all the tonally tweakable elements in the extensive chain of components that define your sound as a guitarist, the tubes tucked into your amplifier might be the most enigmatic. Working symbiotically with the circuits and transformers housed alongside them, these tubes help to determine the way your playing is translated, from the signal produced at the guitar’s pickups to the sound waves ultimately pumped into the air by the speaker and broadcast to listeners’ ears. Given their role in the signal chain, tubes can greatly influence the feel of your playing, as well as the sound.

Alternative guitar amp options have threatened to bury tubes for six decades—since the arrival of solid-state amps in the 1960s to the proliferation for modeling amps in recent years. Yet the rumors of the tube amp’s death have been greatly exaggerated, and they continue to be used by more pro and hobby players around the world than any other type of amplifier. Even the sounds of modeling rigs are based on the tone and playing feel of myriad classic tube circuits.

Didacts will occasionally argue that tubes themselves don’t have a sound. Certainly, that’s true as far as the silence you’ll hear if you unplug a tube and hold it up to your ear. So, sure, the design and circuit of the amp in which any tube is used sets the foundation of its overall tone. But tubes do very much enhance or define certain sonic characteristics of amps, which is something you discover pretty quickly when you swap one tube type for another (in amps that allow this)—only to discover a distinct shift in your amp’s tonal personality.

“A survey of many classic and boutique amps usually reveals specific tube types enhancing distinct sonic characteristics time and again.”

It’s probably best, therefore, to think of many classic amps and traditional tube types as working hand-in-hand to present familiar sonic templates. For that reason, throughout this guide we’ll nod to a handful of familiar amplifier makes and models when referencing many tubes—and output tubes in particular, since the most common preamp tubes are often interchangeable between drastically different amp designs.

Also, while it might be true that a good amp designer can coax nearly any tone out of any conventional type of output tube, a survey of many classic and boutique amps usually reveals specific tube types enhancing distinct sonic characteristics time and again. For example, Dick Denney might have built the most famous iterations of the Vox AC15 and AC30 around EL84s, because they were plentiful and affordable, but now that those sounds have been blueprinted, we know which tubes to turn to for consistently achieving them.

Let’s start our guide with a look at the main output tube types used in guitar amps, then we’ll move on to common preamp tubes. Per-tube prices quoted are for current or recently manufactured examples made in Russia, Eastern Europe, and China, as surveyed at reputable dealers such as Mojotone, Antique Electronic Supply, Sweetwater, Telefunken, the Tube Doctor, EHX, and the Tube Store. Tags for special or limited versions of tubes are typically a little higher.

Output Tubes

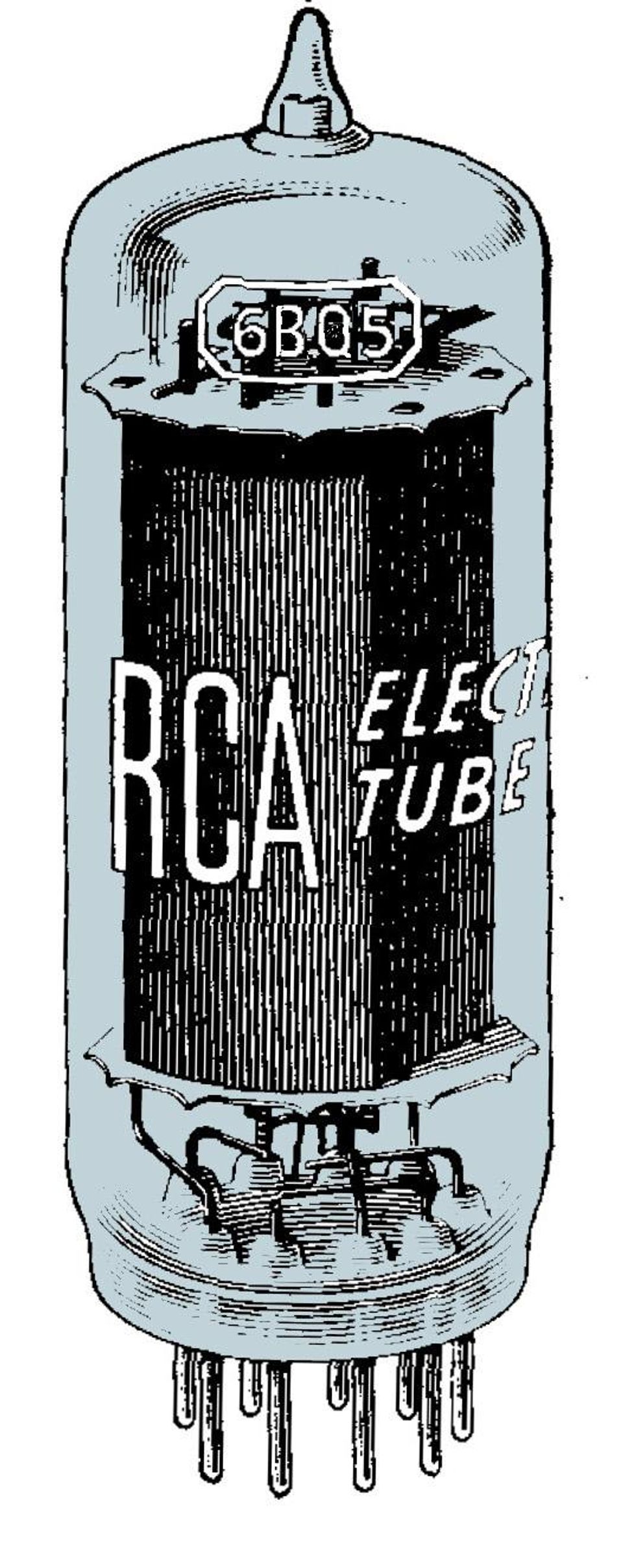

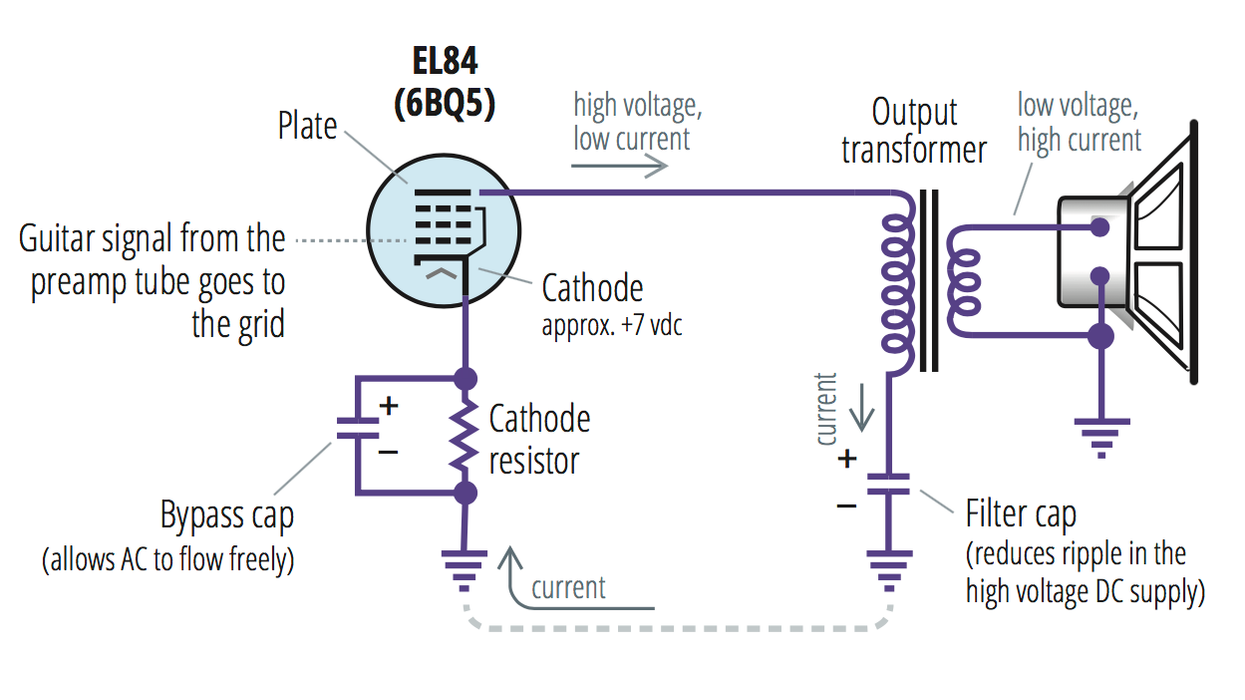

Output tubes (also called power tubes) are the larger of the tube types within your amp and are usually found toward the opposite end of the chassis from the amp’s input. These tubes receive the guitar signal that the preamp tubes have already amplified slightly and amplify it much more, into a signal that can be pumped through a speaker via an output transformer. Let’s take a family-by-family look at these tubes

6L6 Types

Tone Template: Big American

Price: $25 to $50 street

Courtesy of The Tube Doctor

Used in pairs for 35 to 50 watts or quads for 80 to 100 watts, 6L6s are the classic big American tube, probably best defined by the sound of the larger, legendary Fender amps of the ’50s and ’60s: the tweed Bassman, the black-panel Twin Reverb, the Super Reverb, and more. This tube has a bold, solid voice with firm lows and prominent highs. The sound can almost be strident in loud, clean amps that were designed for maximum headroom, or silkier and more rounded in smaller amps—like many of the tweed era—that allow for easier and earlier clipping.

Different 6L6s offer varying types of tonal performance. The 6L6GB and 6L6GC, for example, are a little softer/rounder and firmer/bolder, respectively, while the latter is also capable of handling higher voltages and delivers later breakup with increased headroom. (Note: These aren’t better/best distinctions. Either tube may be preferable according to your sonic needs, or might be required by your amp’s specifications.) A “W” designation on either of these denotes a more rugged tube originally intended for military use.

“6L6s are the classic big American tube, probably best defined by the sound of the larger, legendary Fender amps of the ’50s and ’60s.”

The original 5881 tubes manufactured in the U.S. in the ’50s and ’60s are a tougher sibling of the 6L6. They put out a little less power and break up a little earlier than the 6L6GC. Currently manufactured 5881s, however, are usually 6L6 types that have been relabeled, and therefore don’t vary greatly in their characteristics. If you’re lucky, you might find some new old stock (NOS) originals (see sidebar at bottom of page).

In many amps, all of the tubes mentioned in this 6L6 section can be swapped for each other, with some caveats. Always refer to your amp manufacturer’s instructions before doing so, and be aware that higher-powered amps designed with 6L6GCs in mind might run at voltages too high for 6L6GBs or 5881s.

For a further sonic reference point, 6L6 types also appear in many vintage Gibson, Silvertone, Danelectro, and Valco amps, plus early Marshall JTM45s, many Mesa/Boogie Mark Series models, Dumbles, many powerful Soldano and Bogner amps, and boutique favorites like the Carr Rambler and Dr. Z Z-28 MkII.

EL34s

Tone Template: British Stack

Price: $23 to $50 street

Photo courtesy of Telefunken

EL34s, used in pairs for 45 to 60 watts or quads for 100 to 120 watts, are responsible for the archetypal 50- and 100-watt tone from across the Atlantic, as delivered by the classic Marshall plexi variations. It is characteristically thick and mid-forward, with round lows, crispy highs, and a slightly granular texture overall—and smoothly compressed and aggressive when driven hard. The EL34 can also deliver tighter and bone-crunchingly punchy sounds to arena-rock stages in amps that can be pushed up to 120 watts with sets of four tubes, such as the Hiwatt DR103. That’s thanks to this tube’s ability to handle very high plate voltages.

The EL34 is featured in post-1967 Marshalls like the JMP50 and JMP100 plexi and metal-panel amps, later Master Model 2203s and 2204s, JCM800s, and the majority of modern models. These tubes are also used by (as mentioned) Hiwatt, Orange, and Sound City, and in Vox’s AC50 and AC100, as well as several amps from Selmer and Traynor. Contemporary makers seeking that Brit-stack kerrang! at full volume usually turn to EL34s, so they are also part of the formulation of high-gain-design builds from Rivera, Bogner, Friedman, and Mesa/Boogie, as well as the Matchless Clubman, TopHat Emplexador, and Komet K60.

KT66s

Tone Template: Bold British

Price: $45 to $70 street

Courtesy of The Tube Doctor

This large, imposing Coke-bottle of a tube was Britain’s response to the American 6L6. As such, it has broadly similar characteristics and produces roughly the same wattage in pairs and quads, although it can handle higher voltages and adds its own sonic personality to the brew. Given this, the KT66 can be used in place of 6L6GCs in many amps, although you should check your manufacturer’s guidelines just to be safe.

The KT66 is probably best known, in vintage amps, for its use in many Marshall JTM45s of the early ’60s, which started with 6L6s and 5881s (following their inspiration of Fender’s tweed Bassman circuit) before moving to the British-made tube when the American “valves,” as the Brits call tubes, became scarce in the U.K. In recent decades, the KT66 has been rediscovered by many boutique amp makers. It’s the tube of choice for the Dr. Z Route 66 and the original single-ended Carr Mercury, among others. Along with its good balance and clarity throughout the frequency range, the KT66 generally offers a slightly bolder low end than the 6L6, and what some players hear as a sweeter, juicier midrange response—making it something of a good blend of the 6L6GC and the EL34.

6550s and KT88s

Tone Template: Punchy, Powerful, and Surprisingly Versatile

Price: $50 to $80 street

Courtesy of Telefunken

A big, powerful tube capable of producing massive wattage in the right circuit, the 6550 has also been used somewhat against type by a surprising number of creative boutique amp makers. In the late ’60s and ’70s, the 6550 was more likely to be found in bass amps—six of them created the original Ampeg SVT’s stadium-rumbling tones—but was also used, for a time, in Marshall guitar amps exported to the U.S. because its ruggedness and greater availability eased servicing issues.

Sonically, the 6550 is bold, clear, tight, and well-composed, with very little compression when pushed, but an aggressive, muscular crunch when it does begin to break up. Some makers—George Alessandro, for one—have cleverly used it to achieve more nuanced tones, but usually it’s a tube that’s employed when massive wattage is the ultimate goal.

Courtesy of The Tube Doctor

Although not identical to the 6550, the KT88 is a common substitute that presents many of the same characteristics. Sonically, it leans somewhere between the 6550 and EL34, but with the tighter low end and massive output of the former. It can usually be swapped directly for a 6550, and often for an EL34, with some slight modifications (as ever, consult your manufacturer or a good amp tech). The mighty 200-watt Marshall Major is the best vintage reference point for this output tube, but it has also been used more recently in the RedPlate BluesMachine and Fryette Sig:X, among others—generally amps seeking either high headroom or a greater proportion of preamp-tube overdrive to output-tube distortion.

“If you’re curious about the sonic effects of variations in 12AX7s that can be used in your amp, it’s worth trying a few to check out the phenomenon for yourself.”

6V6GTs

Tone Template: Juicy, Smaller American

Price: $22 to $55 per tube

Courtesy of Telefunken

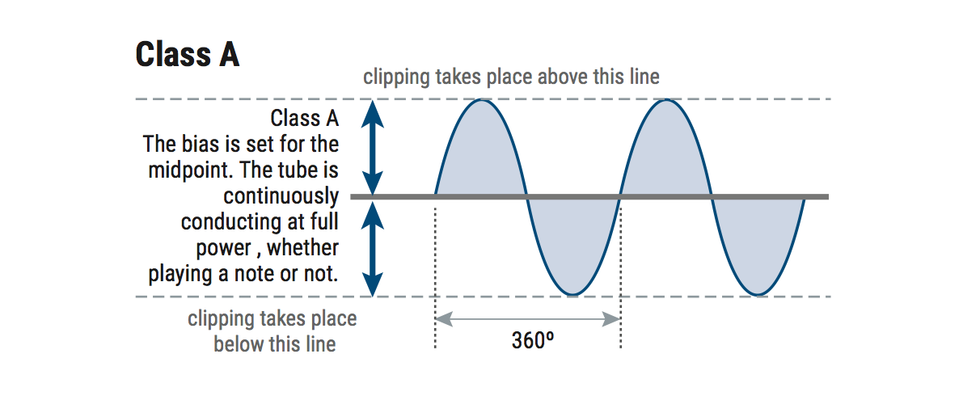

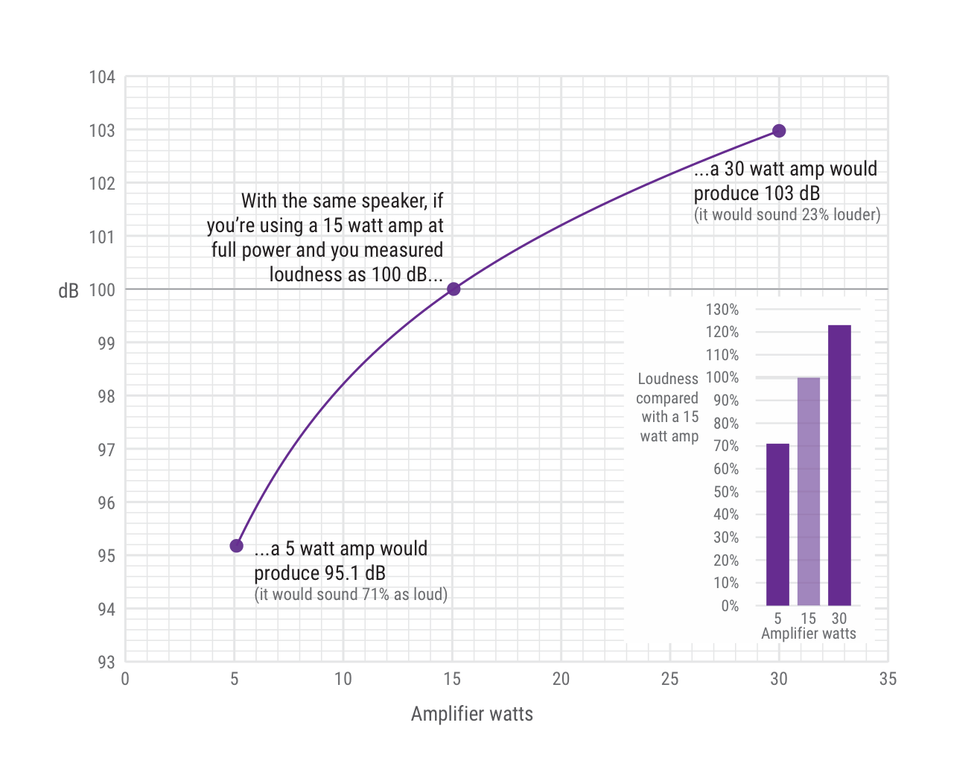

Originally an American-made tube (though later produced elsewhere), the 6V6 is often thought of as the little brother of the 6L6. But, despite its use in the smaller- to medium-sized amps made by golden-age American companies of the ’50s and ’60s—who used 6L6s in their larger amps, it really has a sonic signature all its own. A pair will generate around 15 to 18 watts in a cathode-biased amp (think tweed Deluxe) or upwards of 22 watts in a fixed-bias circuit (Deluxe Reverb), and they were also sometimes used in quads to produce 30 to 50 watts. Their sonic personality? Round, rich cleans and a juicy, relatively mid-forward sound when pushed into distortion, with notable compression and a hint of granularity at the core.

In addition to the notable Fender models the 6V6 appeared in, these tubes were also deployed in the most popular Gibson amps of the ’50s and have been used in near-countless reissue and boutique models over the past couple of decades. The Tone King Imperial, Bogner Goldfinger 45, Carr Mercury V and Skylark, Divided By 13 CJ 11, and Victoria Silver Sonic all used 6V6s in their output stages.

EL84

Tone Template: British Chime

Price: $17 to $38 per tube

Courtesy of Electro-Harmonix

In something of a parallel to the American 6V6, the EL84 (originally a British and European tube) is often talked of as a “junior EL34,” although, again, it has a personality very much its own. This tube is notable for being the only 9-pin (noval) tube in our selection (most tubes are octal, having 8 pins), and it can look much like a taller preamp tube. The EL84 delivers around 15 to 18 watts in pairs, or from 30 to 36 watts in quads.

Far and away most famous for its use in the Vox AC15 and AC30, the EL84 is known for its sweet, bright, chimey clean tones and succulent, textured, harmonically saturated overdrive. “Shimmer” and “bloom” are among the adjectives players use to describe EL84s in the sweet spot, just at the edge of breakup. In addition to the archetypal original Vox amps and later reissues, the EL84 has been popular with a long list of other companies, including boutique builders who clearly take their inspiration from the British classics.

Popular amps like the Matchless Lightning, Spitfire and DC-30; Dr. Z Carmen Ghia and Maz (the latter has two equivalent 6N14Ns power tubes); 65amps London and Soho; TopHat Club Royale; Friedman JJ Junior; Mesa/Boogie Mark Five: 25 and 35; and Fender Blues Junior and Pro Junior all use this tube.

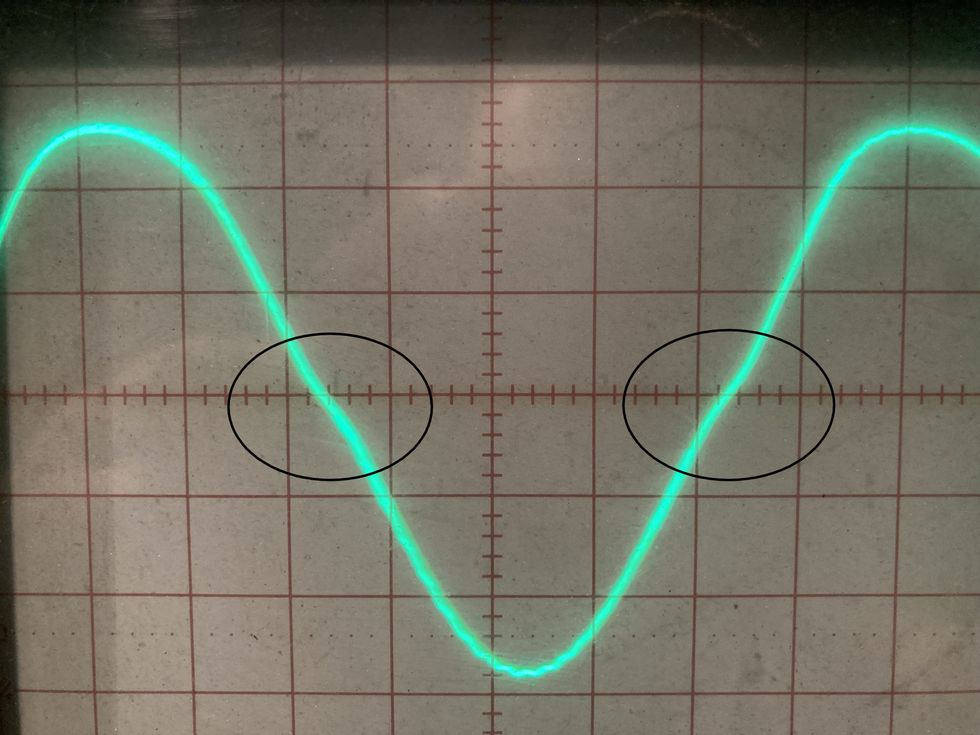

Preamp Tubes

Generally speaking, preamp tubes are less likely to define the foundational sound of any given amplifier, although swapping one for another—even of the same type, but a variation or a tube from a different maker—can still impose a noticeable change on your tone. One reason we think of preamp tubes as less of a defining element in most guitar amps is because the vast majority of amps use the same preamp tube types. The 12AX7 is far and away the most common preamp tube and has been since the early ’50s. Again, variations on makes of 12AX7s can still stamp elements of their own personality on the sound of any amp, and swapping one manufacturer’s 12AX7 for another might produce dramatic sonic changes, but not the same sort of tectonic shift in the basic characteristics of any given amp as output tubes.

If you’re curious about the sonic effects of variations in 12AX7s that can be used in your amp, it’s worth trying a few to check out the phenomenon for yourself, in order to select a favorite. Otherwise, it’s probably more informative to discuss their different levels of gain available via various preamp tubes. That will alter the sound and feel of most amps, since the proportions of clean and overdriven sound, the point on the volume control at which distortion sets in, and other gain-related factors all play a big part in shaping what we think of as our tone.

Each major type of preamp tube exhibits what we call a “gain factor,” and the relative comparison of this spec gives us some indication of how hard that tube will drive the preamp stage of any amp. To that end, despite the 12AX7’s domination of the market, let’s also look at a few other tubes, too. (Note: We’re only discussing common 9-pin (noval) preamp tubes here, but the lesser-used, octal-based preamp tubes, more common up until the early to mid-’50s, are still enjoyed by some players.)

Dual-Triode Preamp Tubes

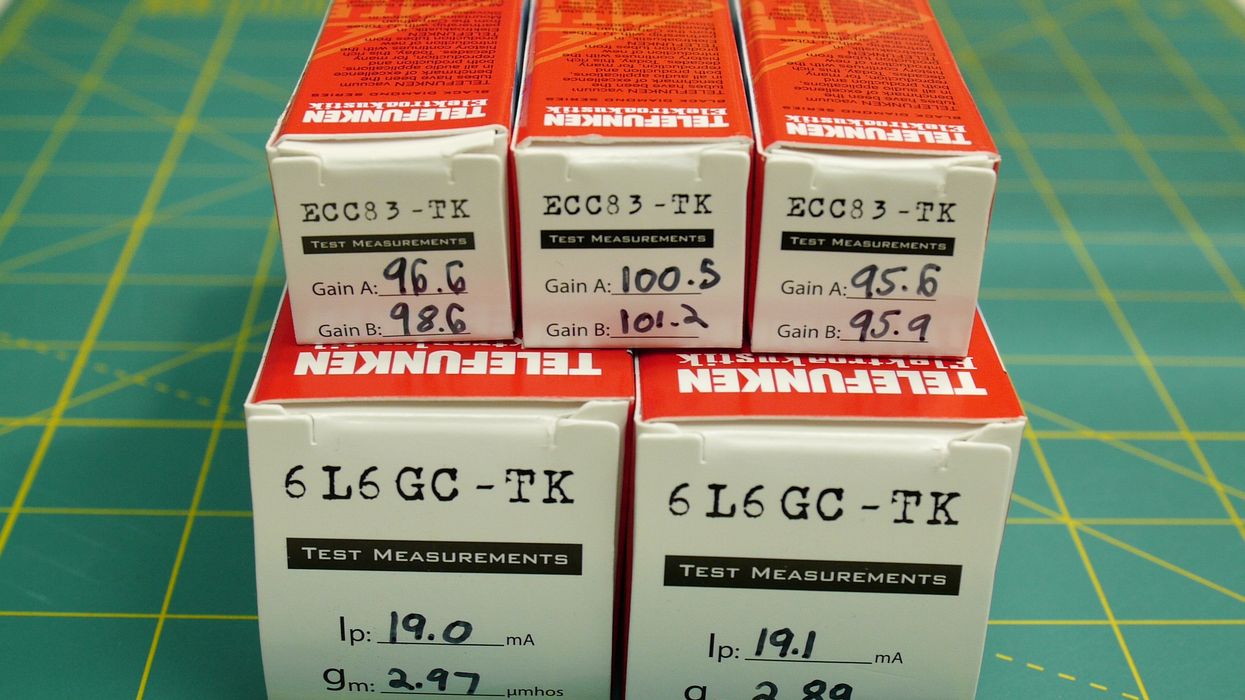

12AX7s (aka ECC83s), 5751s, 12AT7s, 12AY7s

Price: $18 to $35

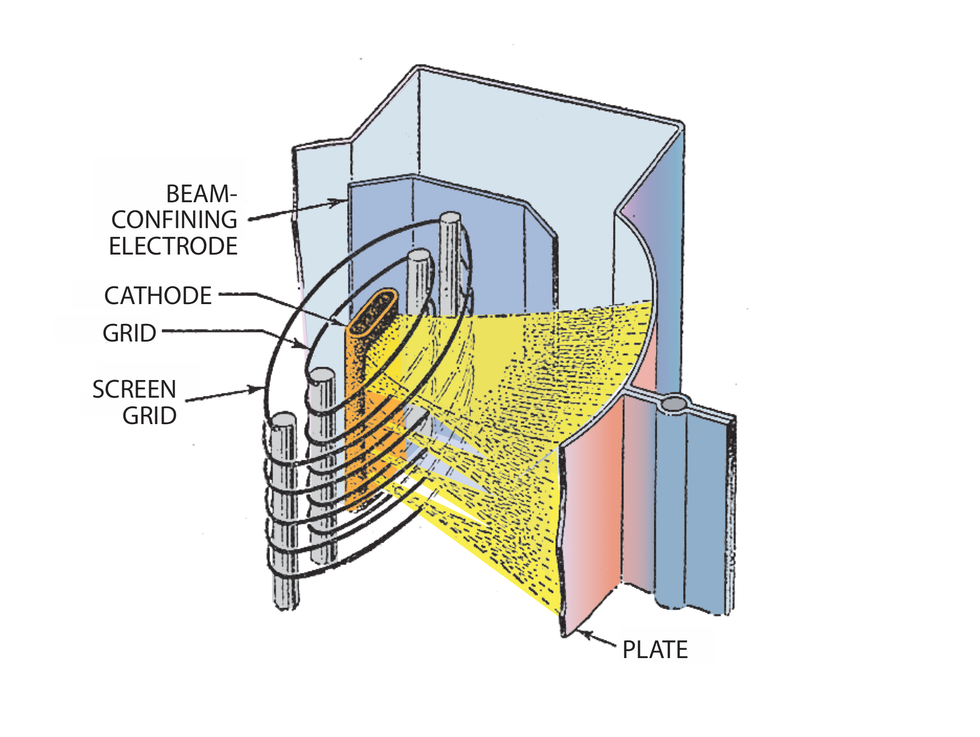

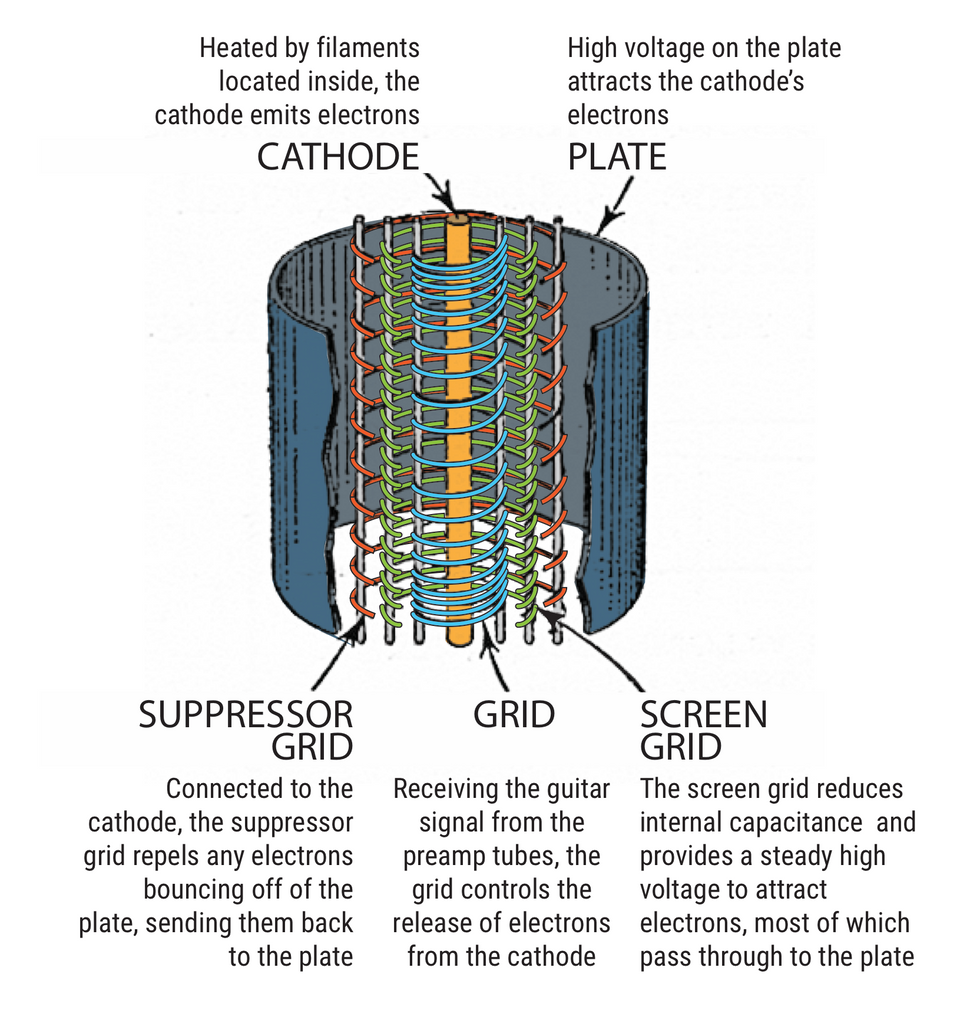

Each of these tube types contains two triode gain stages within one bottle—hence, the “dual-triode” name—and they can perform their duties in two parts of the preamp circuit simultaneously using each triode. [Each triode gain stage consists of three electrodes: a cathode filament, anode plate, and control grid. For more background, check out Dan Formosa’s article “Tube-Amp Basics for Beginners,” in the June 2021 issue, or at premierguitar.com.] In theory, any one of these tubes—listed above in descending gain levels—can be substituted for each other with little chance of damage to your amplifier. Technically, the 12AT7 is usually biased differently than the others, so might not perform optimally in a circuit set up for a 12AX7, but you’re unlikely to damage your amp by trying it out. (If you’re curious, swap it in for a short period of time, and if you like the results, check with your amp’s manufacturer or a good tech before using it full-time.)

By the way, here are the specific gain factor ratings—the measures for how much a tube amplifies the input signal—for these tubes:

12AX7: 100

Courtesy of the Tube Doctor

5751: 70

Courtesy of Electro-Harmonix

12AT7: 60

Courtesy of Electro-Harmonix

12AY7: 40

Courtesy of The Tube Doctor

The main effect of swapping between these tubes of descending gain factors will be increased headroom and a later onset of distortion as you run down through the ranks. Each comes with its own nuanced sonic characteristics, too, which are difficult to define when divorced from the specific circuit in which they are used. Note, however, that many players find the 12AT7 (most commonly seen in reverb and phase-inverter positions) to be a little dull or cold-sounding, even as compared to the lower-gain 12AY7.

The 12AY7 is notable for its use in the first gain stage of most tweed Fender amps of around 1952 to ’60. Over the years, many players have swapped these for more common 12AX7s, which delivers earlier breakup and is desirable for some playing styles. This hotter tube can lead to a somewhat “fizzier” distortion when pushed hard in this type of circuit, though, and the 12AY7 is still considered to deliver the proper tone of classics like the 5E3 Deluxe, 5F4 Super, and 5F6-A Bassman.

Pentode Preamp Tubes

EF86, 5879

Price: $35 to $200

Courtesy of The Tube Doctor

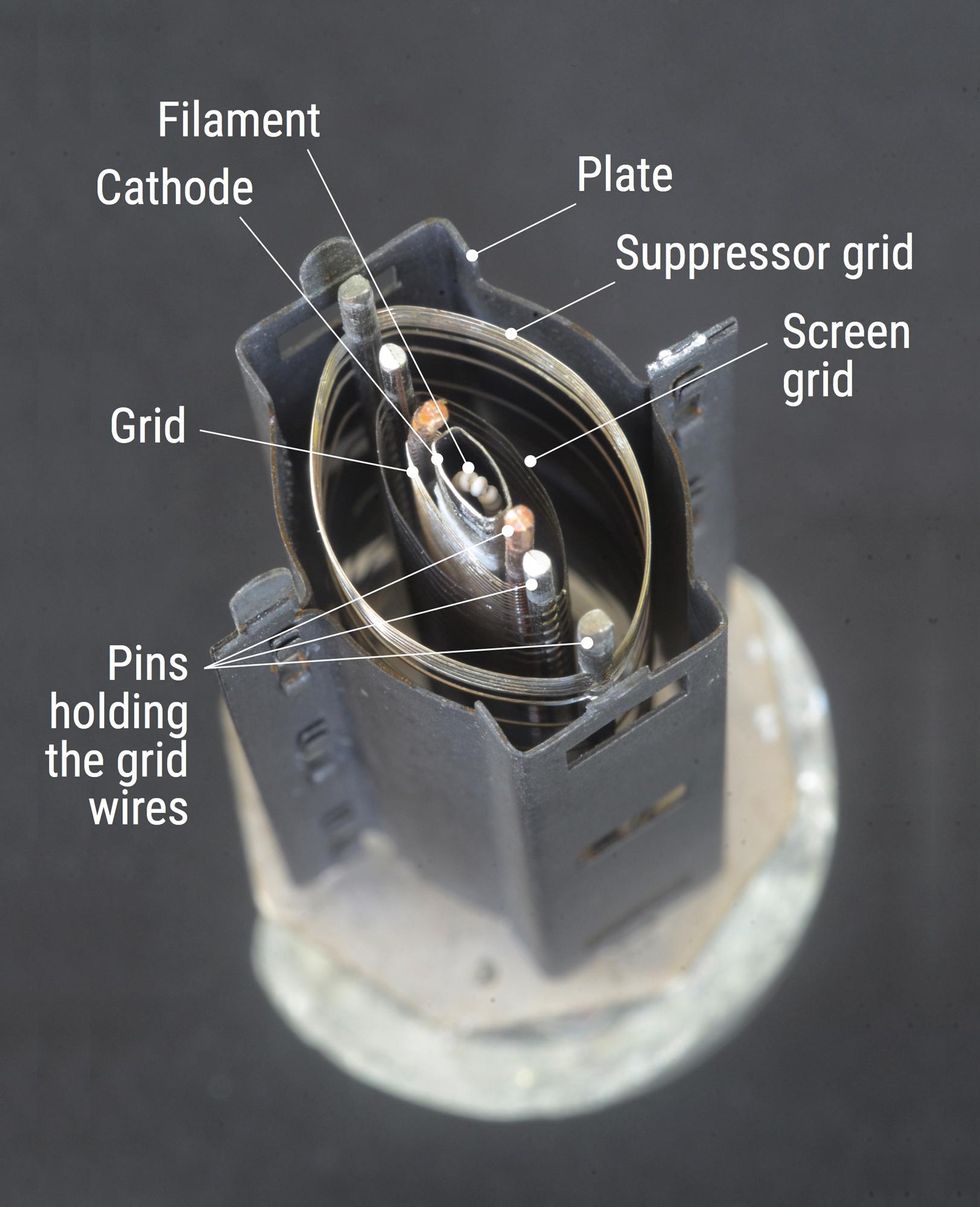

Seen far less often but still beloved by some players, the pentode preamp tube houses a single pentode gain stage within a glass envelope that’s otherwise identical to the 12AX7 and the others above. As you might guess, pentode tubes have five electrodes, with screen and suppressor grids added to the 12AX7 family’s three. These are not, however, interchangeable for dual-triode tubes, so don’t even try it!

The most common pentode preamp tube is the EF86 (aka 6267), found in the classic iteration of the early ’60s Vox AC15. This tube reputedly has an even higher gain factor than the 12AX7—although the exact number is debated—and is characterized by a fat, rich sound. It’s prone to less self-distortion than the dual-triodes, too, meaning it passes a full-frequency signal along to the next stage in the amp without adding much of its own fizz or sizzle, although it can certainly contribute to tube overdrive. It also resists collapsing into mush when hit by an overdrive pedal in front of the amp. Boutique amps that employ the EF86 include the Matchless DC-30 (in channel 2, for high gain), the Dr. Z Z-28, and the Matchless DC-30.

Another pentode tube is the American-made 5879, which has similar characteristics to the EF86, although it also has different internal pin connections and therefore cannot be used in place of it. Probably best known for its use in the Gibson GA-40 Les Paul amp of the late ’50s, this one has most notably been employed in several current models from Divided By 13.

The Skinny

Okay, now you know all the basics about tubes. Use it as you will—to experiment, to hold your own in debates with fellow gear nerds, or as another stepping stone on your path to becoming a tone sensei.

Follow Your NOS

Courtesy of the Tube Store

Courtesy of the Tube Store

Courtesy of the Tube Store

As you get deeper into the world of replacement tubes for guitar amplifiers, and particularly if you fuel your knowledge by perusing online forums, you’re likely to come across the term “NOS” again and again, along with the recommendation that those are the tubes you need to buy. Short for “new old stock,” NOS tubes are those that were manufactured many years ago—usually during the golden age of American and European tube production—but have never been used. They are old stock, but are essentially new because they have never been installed in an amplifier.

The demise of the vacuum tube industry in the U.S. and Europe began in the late 1960s and early ’70s, when transistors took the reins for just about all amplification duties other than those of guitar amps. Production dwindled through the ’70s and all but disappeared after, although a few tubes were made in the U.S. (the 6550, in particular) in relatively small numbers right up until 1993. More to our point, though, since the early ’80s all new tubes have been manufactured in Eastern Europe and China, particularly because these regions still needed them for use in military equipment that was slower to update to new tech. It’s worth remembering that once the technology in military and consumer electronics moved forward, the guitar-amp and audiophile markets weren’t enough to sustain the tube industry.

Guitarists have been plundering whatever stocks of NOS tubes they could find for a good three decades or more. So, there aren’t a whole lot of genuine NOS tubes left, and those that remain are very expensive. Beyond this, the bigger issue with acquiring NOS tubes today revolves around quality and verification: a lot of sub-par tubes that were rejected during testing over the years have ended up being recycled as NOS, as have a lot of used tubes pulled from old amps and polished up. Buying NOS from a reputable dealer can help mitigate these issues, but, once again, you will pay a premium. For example, we recently spotted an Amperex Bugle Boy 12AX7 for sale at $349.95. Is it that much better than a JJ Electronic 12AX7 for 20 bucks?

No matter how much chat-room pundits rave that you must use NOS tubes, current (or at least recent) tubes provide good tone and excellent reliability in the vast majority of guitar amps in use today. It’s also worth considering the fact that contemporary amp makers are usually designing and fine-tuning their circuits with current-manufacture tubes in mind, so while a rare and expensive NOS substitute might get a little more out of them, that is by no means guaranteed.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)