Welcome back to Mod Garage. This month I want to give you some insight into putting vintage parts into new electric guitars and explore why so many people are doing this.

The trend to put old vintage parts into electric guitars started years ago and it’s still in vogue today. But besides the hip factor, is it reasonable to do so? What can you expect, and are there specific situations where this makes sense for a new electric guitar? In this column, we’ll have to face some sad and unpopular facts (and myths) about vintage guitars and vintage parts, so not everyone will be happy about this.

In general, the vintage world is not limited to guitars or instruments. The scene includes a lot of categories, such as cars, watches, clothing, furniture, books, electric devices, and much more. But the basic principles are always the same and there are many reasons why someone decides to jump on that wagon.

We don’t have to discuss putting vintage parts on vintage guitars, which seems logical and natural. On a vintage guitar, it’s all about stock condition and authenticity, like on every vintage collector’s item, no matter what it is.

Let’s start with sad vintage “truth” number one:

Today we can build much better electric guitars than ever before.

That’s not really bad news, if you’re not a vintage guitar seller. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying the old vintage guitars are obsolete or bad in comparison with the ones we can build today. But with today’s high-tech equipment, the level of consistent quality is outstanding and close to perfect. All instruments produced that way are more or less completely identical. Vintage guitars, even if built from the same persons on the same day, are virtually all individual items, which for sure is one of the main keys to their magic. And naturally everyone wants to own an individual item rather than an industrial, mass-produced object.

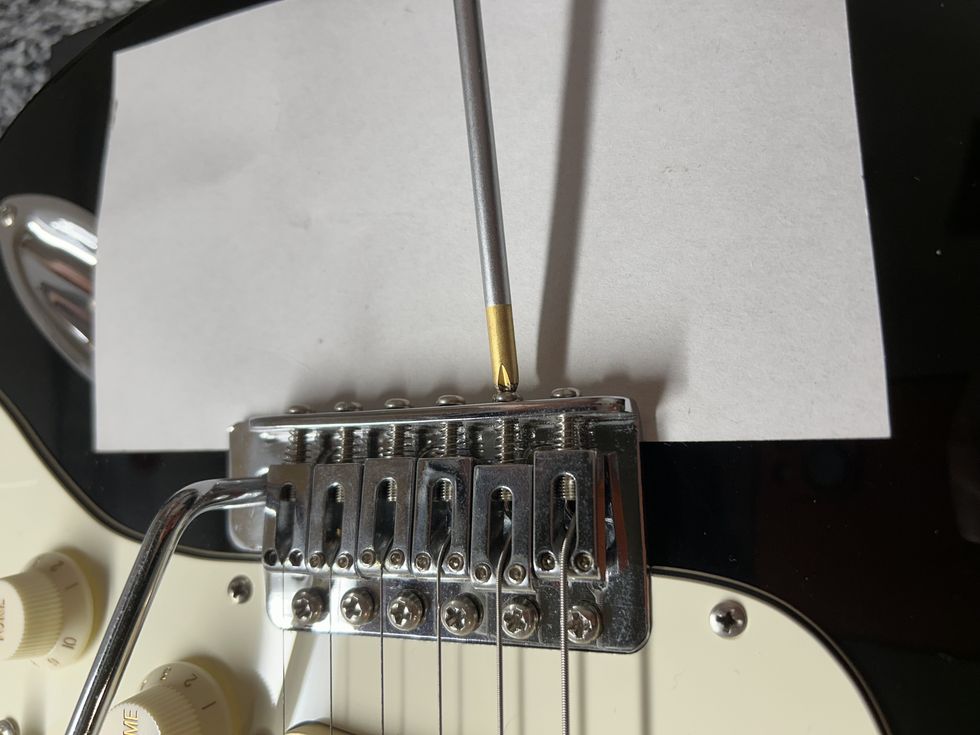

Today we can build tuners that are far ahead of what was possible in the ’50s and ’60s, as well as bridges and tremolos that are little mechanical pieces of art regarding precision and accuracy. So, does it make sense to put vintage hardware on a new electric guitar?

Regarding quality and performance, it’s a clear NO! I have numerous customers doing exactly the opposite, no matter if it’s sacrilege or not. They want to play their vintage guitars but with today’s highest possible performance, so they take out the vintage parts, carefully storing them away, replacing them with modern 1:1 copies to spruce up the old guitars. This is often the case with tuners, string trees, tremolos, and the like, and it’s important that the new parts will fit 1:1 so no new holes need to be drilled to make them fit.

Sometimes imperfection to a certain degree can be exactly the thing you’re looking for regarding tone.

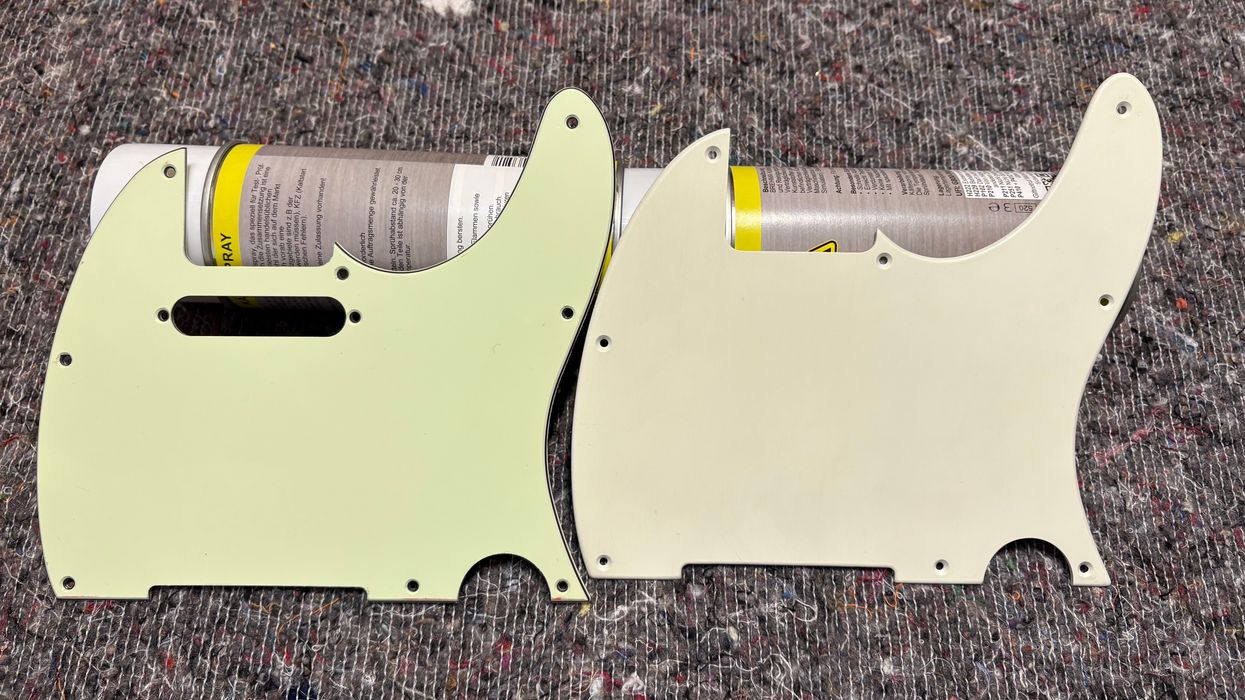

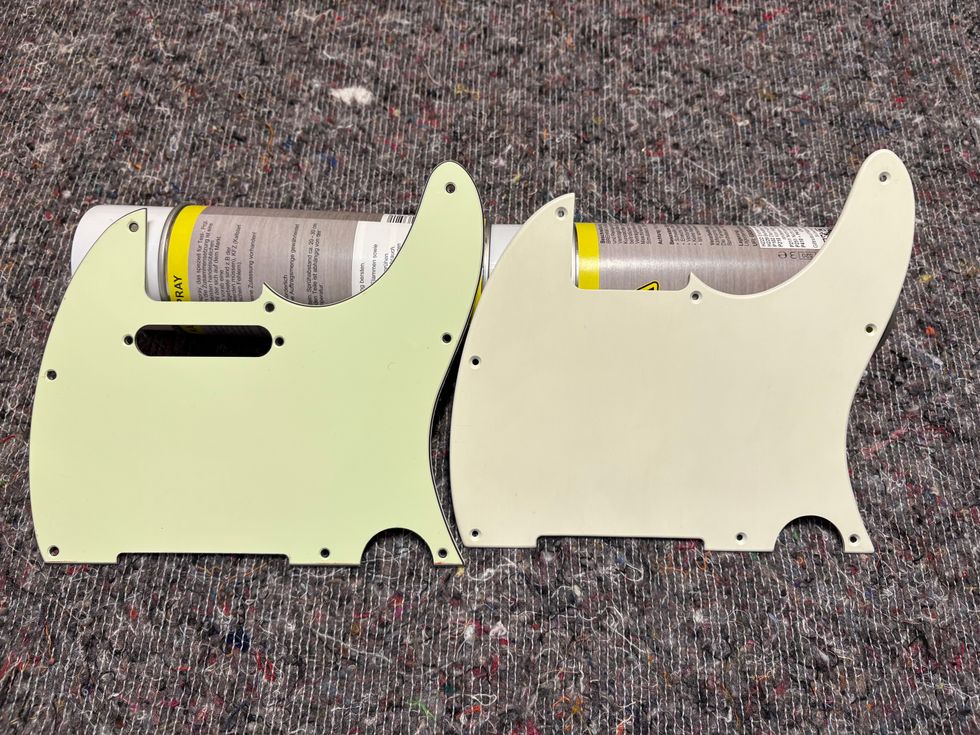

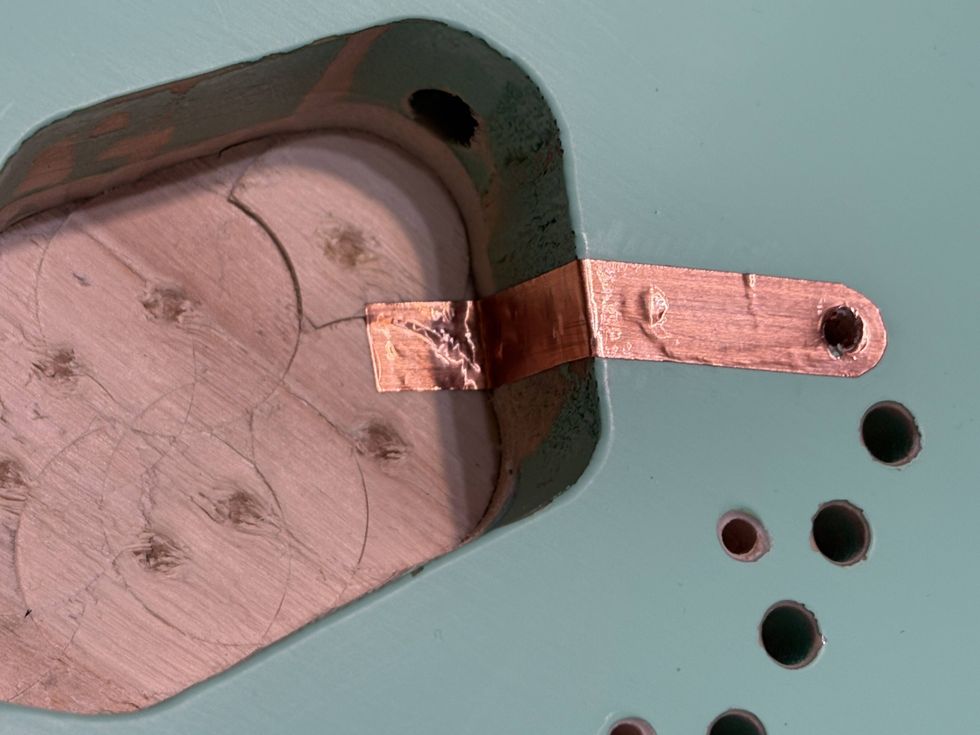

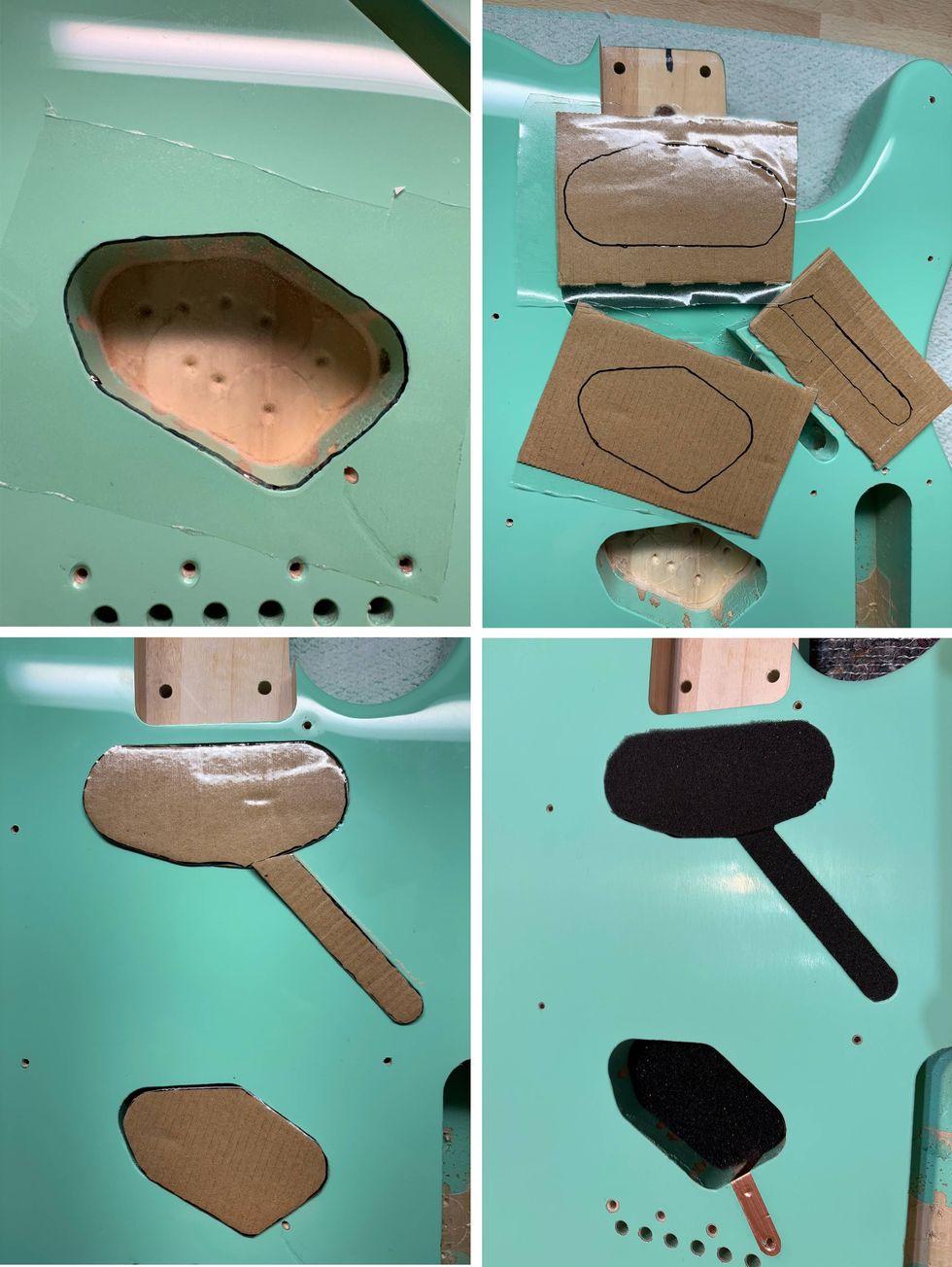

Old and brittle plastic parts like pickguards and pickup covers are also stored away. You can buy modern plastic lookalikes easily and so the old parts are ready to drop in again when you want to sell the guitar someday. Vintage amp players are taking out the original speakers to protect and store them away. This way you can have both: Play your vintage guitar and amp with the highest possible performance, plus keep their value alive because you can always swap parts back to stock condition. I have quite a few customers who take out the complete electronics along with the pickguard, playing a modern substitute under the hood because they don’t want to risk damage to the original. And, believe it or not, a lot of them say the new pickups and electronics sound better than the originals, but compared to the originals, they are worthless. In general, this applies to all vintage items. For example, today it’s possible to build better cars and watches than ever before ... but they don’t make them like they used to, which is one of the number one pro-vintage arguments.

Naturally, there could be other reasons—including emotional ones—to put vintage hardware on a new electric guitar. This is highly individual. Maybe it’s just for fun because it was already lying around, or it looks cooler because it’s used and beaten up. But this can be had cheaper—the market for aged guitar parts is huge. Or maybe one of your favorite artists did something that you want to copy. This also applies to a lot of other vintage stuff like cars and watches—who doesn’t want to drive a Porsche 550 Spyder model like James Dean or wear the same Rolex Submariner 6538 that James Bond wore in 1962 during his first appearance in Dr. No?

But maybe it’s because people think putting vintage parts into a new guitar will increase its value. This leads us straight to sad vintage “truth” number two:

A new electric guitar with vintage parts fetches more money than it does in stock condition.

This is simply not true, at least when sold as one piece with the vintage parts built into the guitar. Like any modification, this will not increase the value of a new guitar—time and being witness to countless auctions has proven this.

But this is the perfect transition to sad “truth” number three:

A vintage guitar makes the most profit when sold completely intact.

Exactly the opposite is true. If you want to make the most profit, nothing beats completely disassembling a vintage guitar and selling it in pieces. I know some vintage parts dealers in Europe and the U.S.—I’ve worked with some of them for over two decades—and they’re all doing the same thing: finding vintage guitars that are for sale, disassembling them, and selling off the individual parts.

One dealer told me this: If you can sell a vintage guitar for $10k, take it all apart and you can make $15k with the individual parts. So, if you put vintage parts on a new guitar that you want to sell, take out the vintage parts and sell them off individually to make top dollar. (It’s not a bad idea to store away any hardware you remove from your guitars, because you might need to put it back in later.)

So, are there any instances where it does make sense to put vintage parts in a new guitar? I would say yes, and I can think of two good considerations:

1. Putting vintage pickups into a new electric guitar.

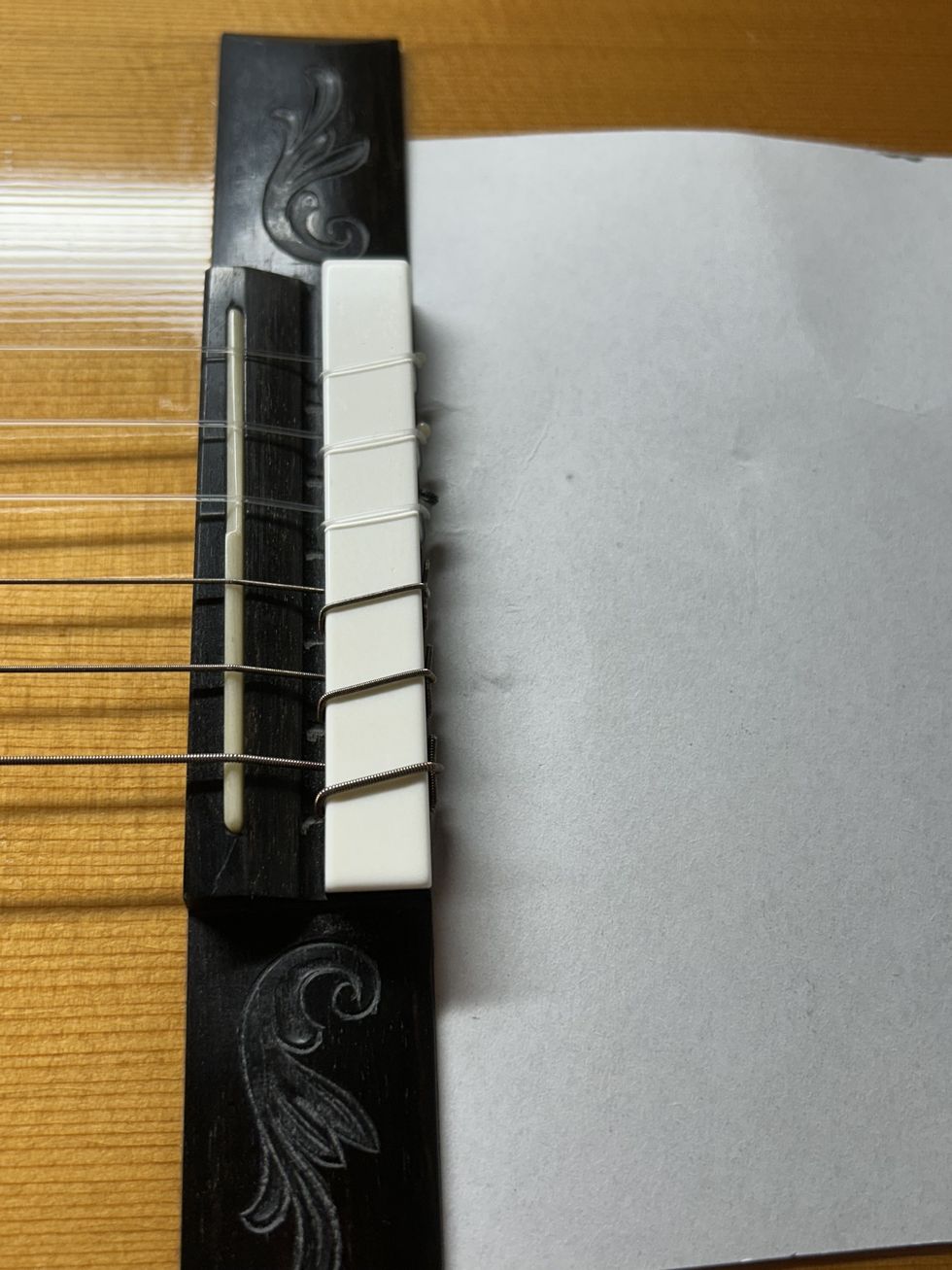

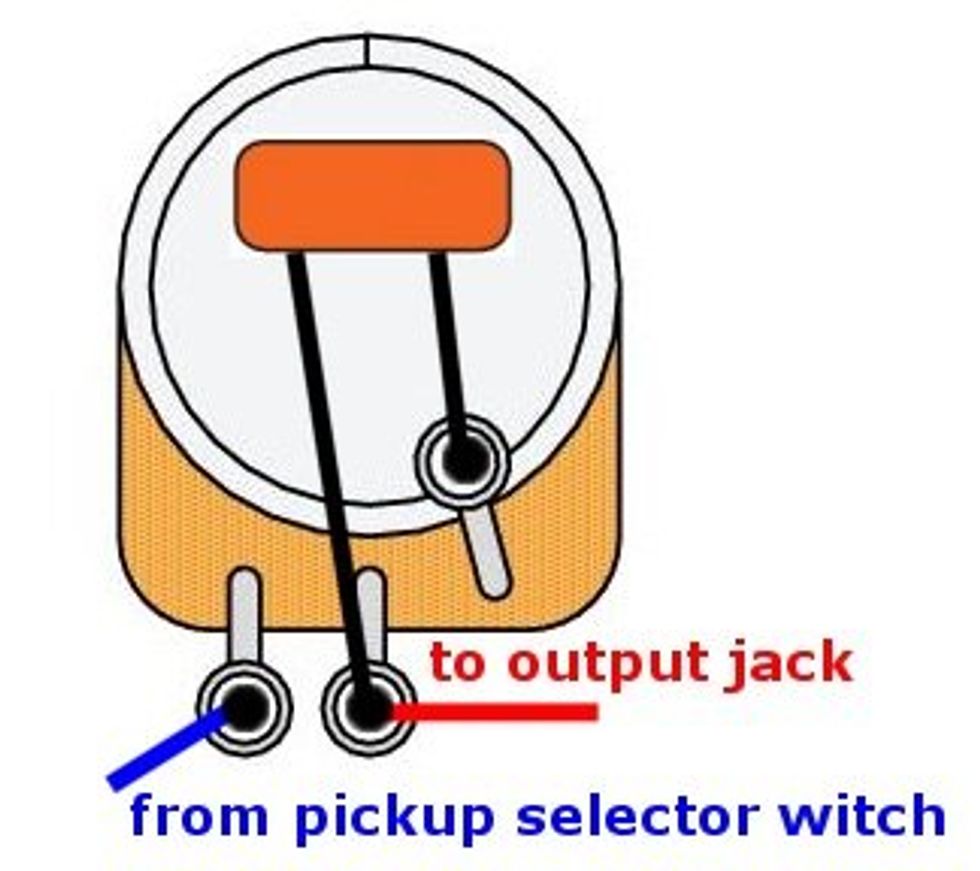

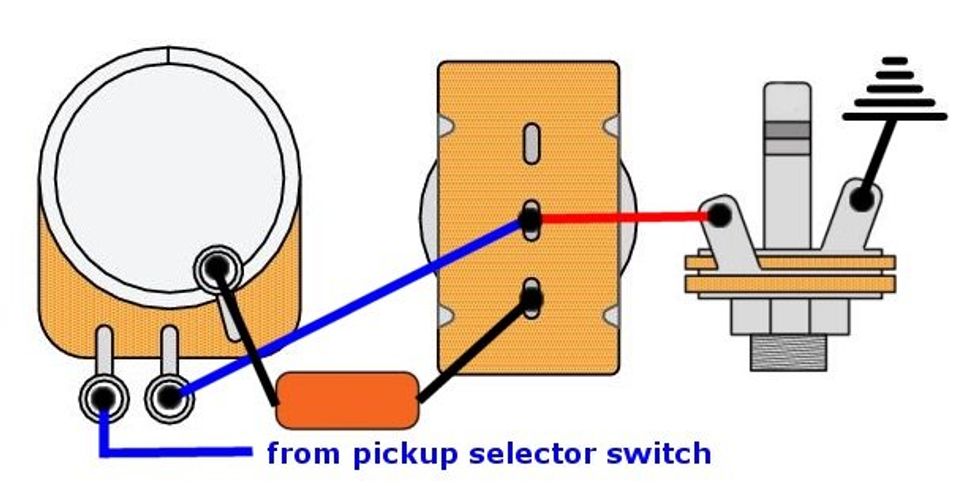

Putting vintage switches, pots, output jacks, and wires into a new guitar is not reasonable. The pickup-selector switches are still made the same way now as they were in the past. Only the materials have changed a bit, enhancing reliability and longevity. So why spend $600 for a vintage CRL 3-way switch when you can get much better performance for $30? A switch has no tone, so leave the vintage switch for a vintage guitar. Same with pots: They don’t have a tone and modern pots are much more reliable. Companies spent years researching the taper and action of vintage pots and you can buy exact vintage copies for only a few bucks. You get the idea.

With a faithful recreation of a vintage pickup plus a vintage tone cap, you can come very close to the magical sound, so investing in a tested NOS tone cap can make a big tonal difference, whereas a new cap can’t.

However, if you fall in love with a set of vintage pickups, it can make sense to put them into your modern guitar. There is no financial risk. They will increase in value, so if you ever want to sell them again you will get more than you paid, enjoying their tone in the meantime. Keep in mind that companies also spent years to analyze, research, and re-engineer vintage pickups and today you can buy almost every given pickup you’re looking for and as close as possible to its original. Such pickups are a lot cheaper compared to a vintage set, but naturally this is no investment.

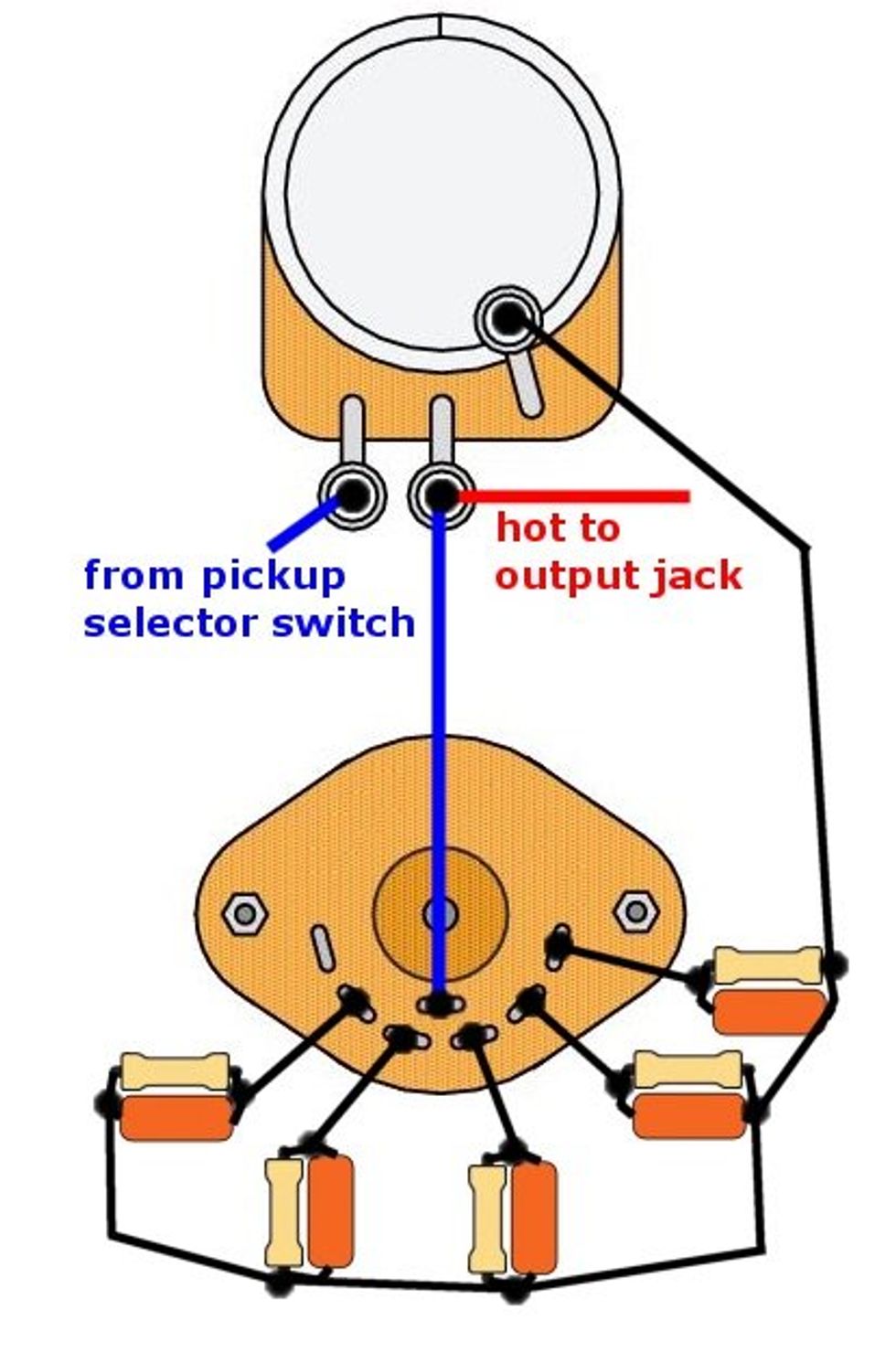

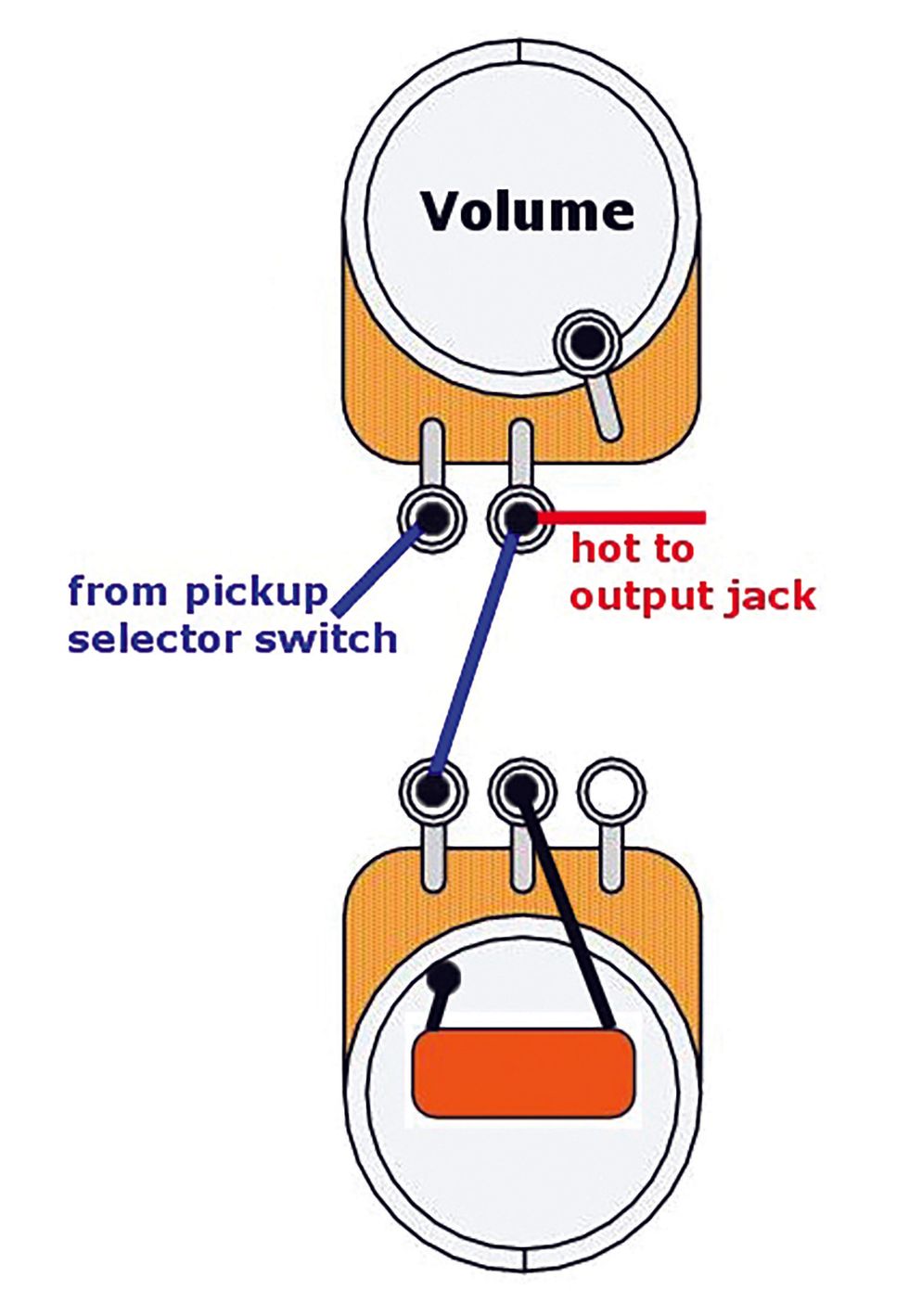

2. Putting vintage tone caps into a new electric guitar.

This is for sure a reasonable procedure to quickly enhance the tone of a new electric guitar. Installing a vintage tone cap into a guitar is also done easily because it’s a simple 1:1 swap with the original tone cap. It’s still possible to find NOS vintage tone caps today, but prices are rising while supplies are running out. Why is this an improvement in tone? The tone of vintage guitars is often described as detailed, harmonically rich, and open. Part of this tone is from the tone cap. Today capacitors are built to perfection and with very low tolerances so they will do a perfect job. In our electric guitars we use them to only short out the highs against ground, leaving the bass untouched ... in very simple words.

Production processes to build capacitors in the ’50s and ’60s were far from perfect, and besides high tolerances in capacitance, certain caps (depending on the dielectric inside) tend to be kind of “leaky” regarding overtones. A modern cap will do a perfect job, filtering out all overtones that it’s supposed to. Most vintage caps will do a lousy job, still letting some overtones through, especially the harmonic ones. This is what makes the tone so rich and detailed, and, by the way, it’s the same situation with tube amps.

With a faithful recreation of a vintage pickup plus a vintage tone cap, you can come very close to the magical sound, so investing in a tested NOS tone cap can make a big tonal difference, whereas a new cap can’t. Sometimes imperfection to a certain degree can be exactly the thing you’re looking for regarding tone. Back in the golden guitar days, no one really cared about such odd details, and even if they did ... it was state of the art and all new technologies were still science-fiction at that time. Today we know better and can use old technology for certain tasks.That’s it for now.

Next month we’ll explore our next guitar mod, so stay tuned. Until then ... keep on modding!