This month, we're going to look at an underused recording technique that can add depth and dimension to your guitar tone. This technique involves two mics: placing one in front of your open-back combo amp or open-back speaker cabinet (like normal) and one behind. A closed-back cabinet (like a 4x12) won't work for this technique, for obvious reasons. This may seem counterintuitive, but, as you'll see, this technique can be very useful—especially when trying to get a more full-bodied sound from a smaller, single-speaker, low-wattage combo amp like a Fender Princeton, Blues Junior, Champ, etc. The Dojo is now open. Let's get started.

Let's talk about the mics first. This technique is extremely flexible and doesn't require that your mics be a matched pair (same make and model). In fact, I've had better results by mixing and matching all kinds of mics! I highly encourage you to experiment and be creative. For this example, I'm going to use a dynamic mic (Shure SM57, $109 street) and a ribbon mic (Rode NTR, $799 street), but, again, any two mics will work regardless of price.

This technique is extremely flexible and doesn't require that your mics be a matched pair.

Mic 1: Shure SM57.

Of the two mics, the mic you use for the front of your amp should be the one you normally use and are most familiar with when recording (Photo 1). This way, you'll be able to have a point of reference as we move forward. After you've gone through this a couple of times, then switch it up, swap mics, and compare the differences.

Mic 2: Rode NTR.

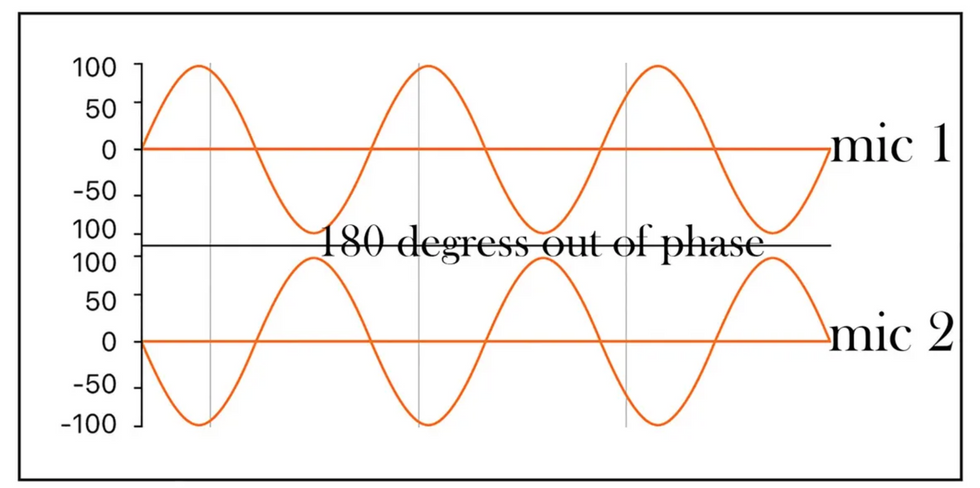

Before placing the rear mic, there is something of critical importance you must do: flip the phase on the recording channel for mic 2. Because this rear microphone is pointed in the opposite direction, it is 180 degrees out of phase relative to mic 1 (Photo 2). We must correct that by flipping the phase on mic 2's mic pre or recording channel. If you don't, when you pull up both mic 1 and mic 2 and listen to them together, you'll find that your guitar tone will sound thin, hollow, and weak—which defeats the whole point of this technique!

Photo 2

I'll explain why this happens in the simplest way I can. When sound waves hit the diaphragm of a microphone (which is a transducer), those waves are converted into a tiny electrical signal with alternating positive and negative charges. When using two microphones pointed in opposite directions with the sound source (your amp's speaker) in the middle, mic 1 will receive a positive (+) charge while mic 2 will receive a negative (-) charge (Fig.1). This is because your amp's speaker can only move in one direction at a time, and it can't send a positive value in both directions simultaneously. This is what causes the phasing issue and why we need to flip the phase of mic 2 so that both mics add their energy together rather than subtracting from each other. Further, if you forget to flip the phase and just listen to only a single mic (mic 1 or mic 2 only), you won't hear the phase issue, but if you listen to both at the same time you will! So … flip the phase.

Fig. 1

Finally, where to place mic 2? There's not a right answer here, because there are too many variables: the dimensions of the amp itself, how open the back is, where the speaker is located (center, off to the left or right), etc. But I've consistently had good luck with placing the mic outside of the amp in the open space about four to six inches away from the back panel of the amp (Photo 3).

Photo 3

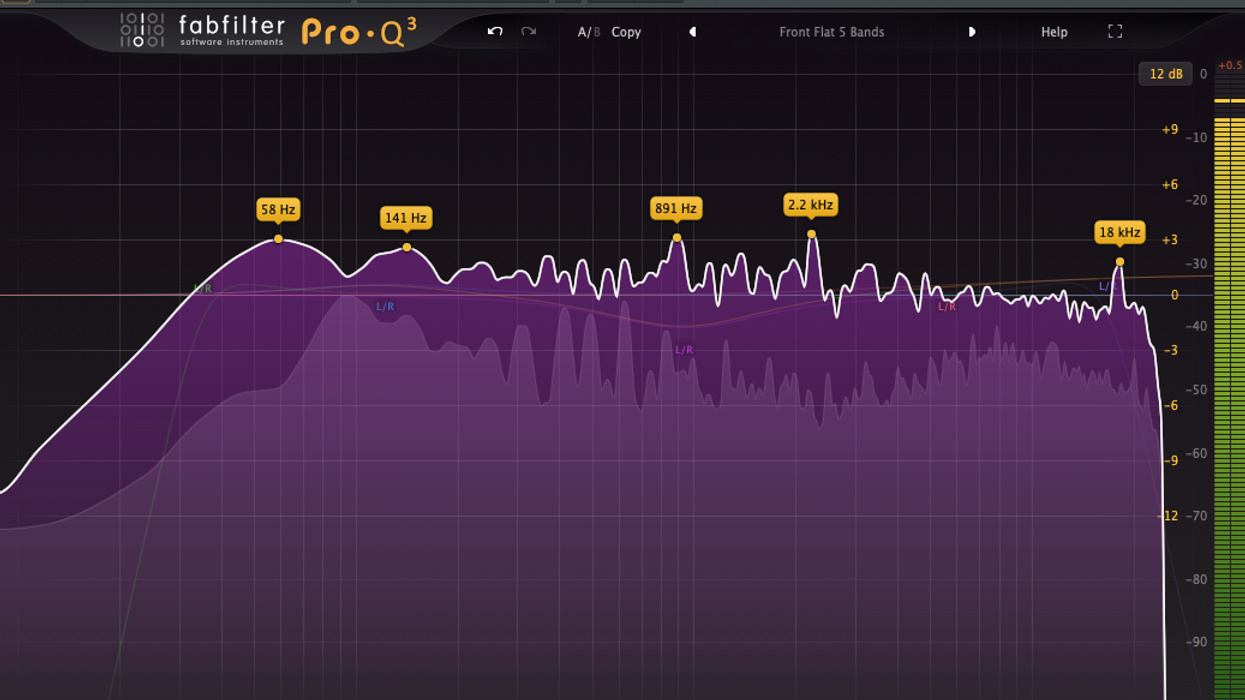

This will give you much more low-end information and beef up your sound. Typically, I'll use an SM57 (or similar) on the front of the amp and a ribbon for the rear, as in this column's example. Ribbon mics naturally have a beautiful low end with significant high-end roll-off the further we go up the frequency spectrum. By placing the darker mic on the back of a small combo amp, I can make it sound like a much bigger amp and get some added mojo as well.

See you next month!

[Updated 8/11/21]