This month we're taking a look at the Fender Greasebucket tone circuit introduced in 2005 on several guitars in the Highway One series, as well as in various Custom Shop Stratocaster models. The Greasebucket name (which is a registered Fender trademark, by the way) is my favorite when it comes to Fender's habit of choosing cheesy marketing names for new products. But don't let the Greasebucket name fool you—your tone will get cleaner with this modification, not greasy and dirty. I tried to find out who came up with this name, but it seems that this info is not documented, which is another Fender habit that began in the early '50s.

Here is what Fender says about the Greasebucket: "The Greasebucket tone circuit adds a new dimension to your tone, the effect is that when rolled down, the tone pot reduces the high frequencies, but does not add bass."

Okay, it sounds like this is worth trying out. In fact, many pro players swear by this tone circuit, and it indeed produces a different effect than the standard tone circuit we all know. But don't take the Fender description literally—a Strat's standard Tone control does not add bass frequencies. With passive electronics, you can't add anything that isn't already there—you can only reshape the tone by attenuating certain frequencies, which makes others sound more prominent. Removing highs makes lows more apparent (and vice versa), and that's exactly what we have here: The standard tone control rolls off some high frequencies (depending on the capacitance of the tone cap), making the bass frequencies more prominent.

In addition, the use of inductors (which is what a pickup behaves like in a guitar circuit) and capacitors can create resonant peaks and valleys, further coloring the overall tone. Some people like this interaction, others don't—it's purely subjective and a matter of personal taste.

Anyhow, the Greasebucket tone control is a cool way to roll off the highs and lows in your guitar while preventing your tone from getting muddy. This is especially helpful for creating sparkling clean tones, but it's also useful for overdriven sounds.

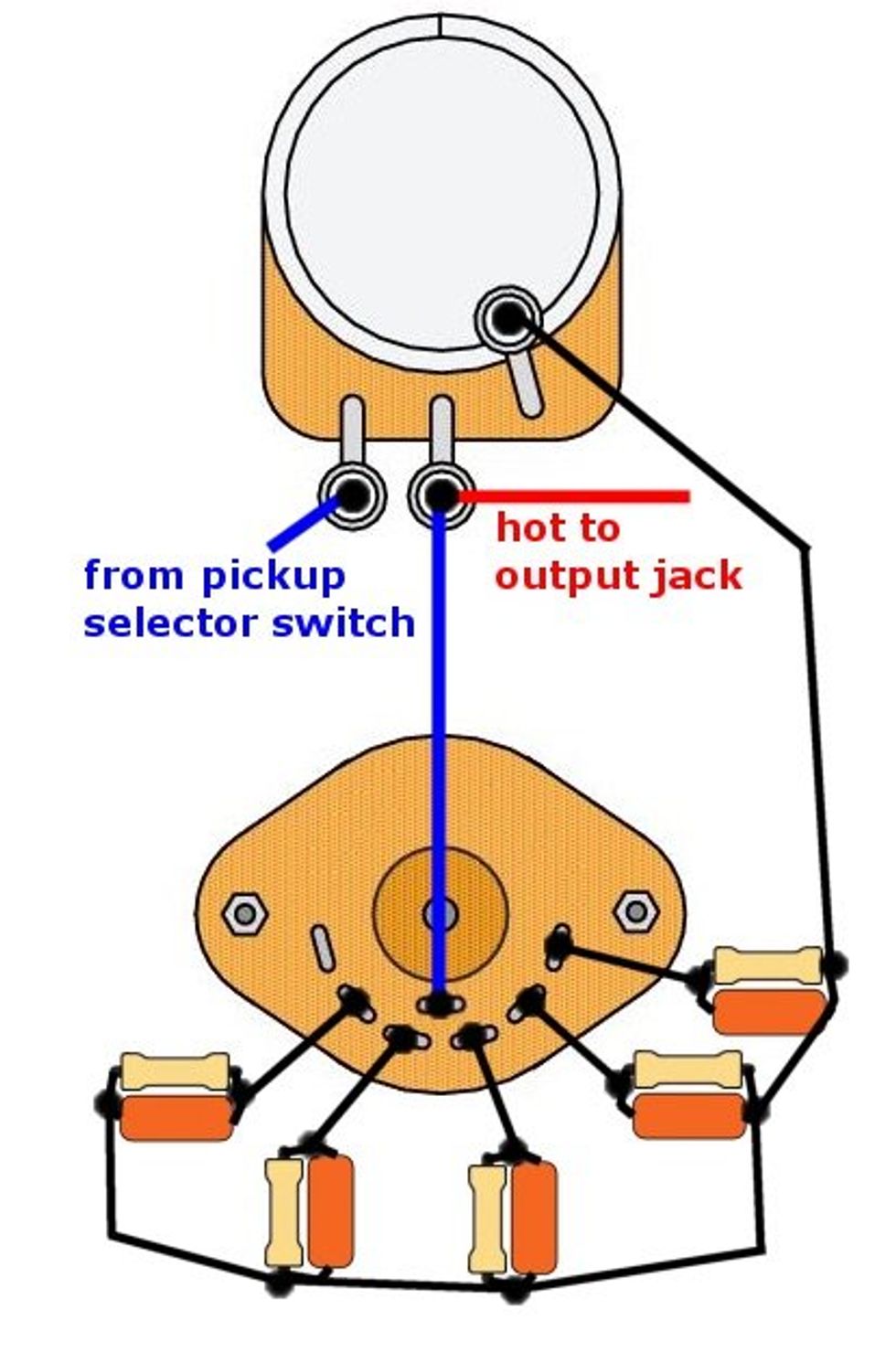

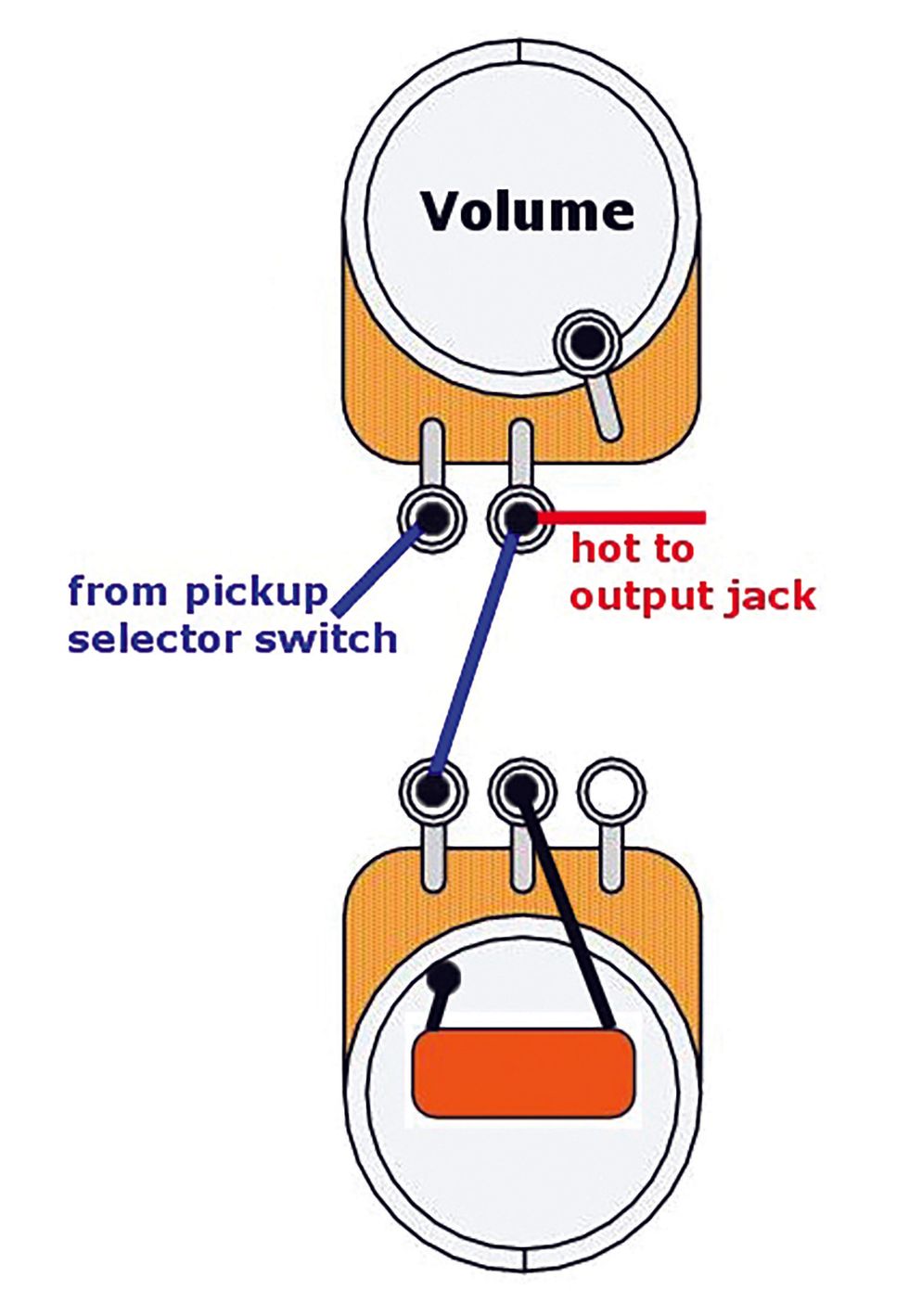

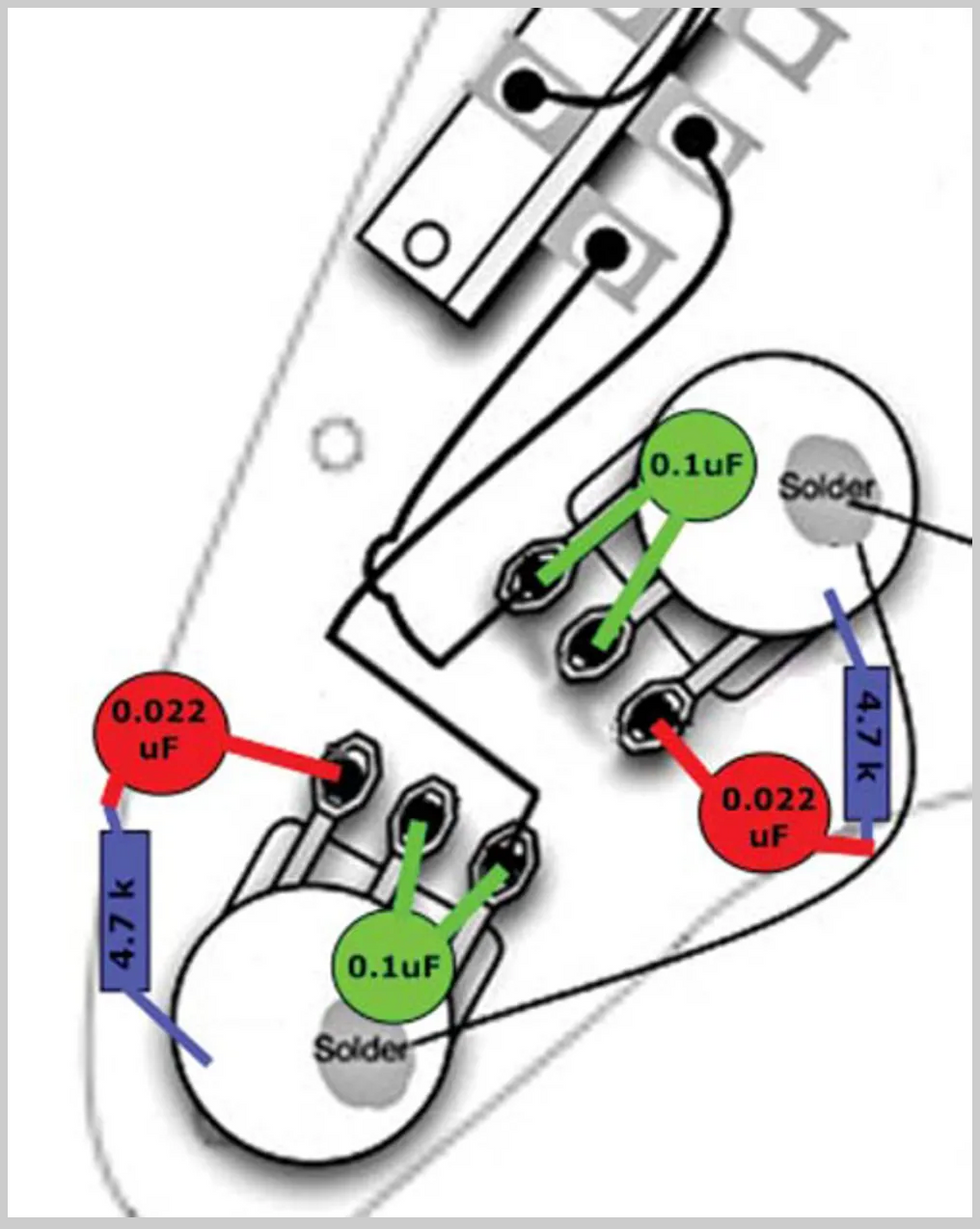

To convert your Strat's normal tone control to Greasebucket specs, you don't need much: 0.1 μF and 0.022 μF capacitors (Fender uses ceramic-disc versions), and a 1/4-watt 4.7 kΩ resistor (Fender uses the metal-film type). If you want to convert both your Strat's tone controls to Greasebucket specs, obviously you'll have to double these parts.

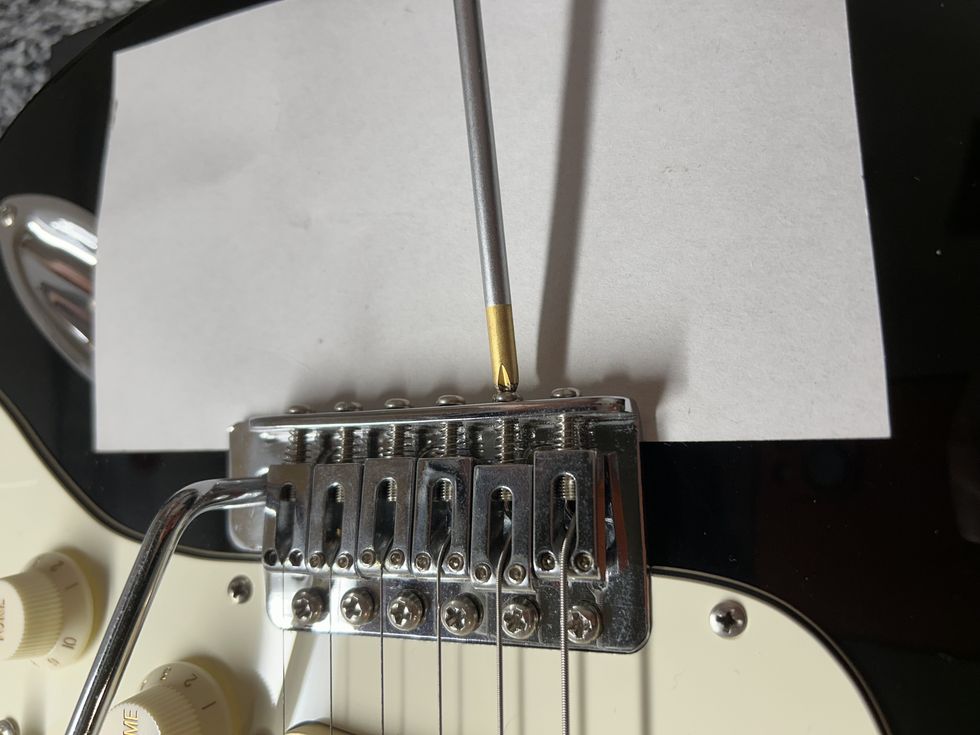

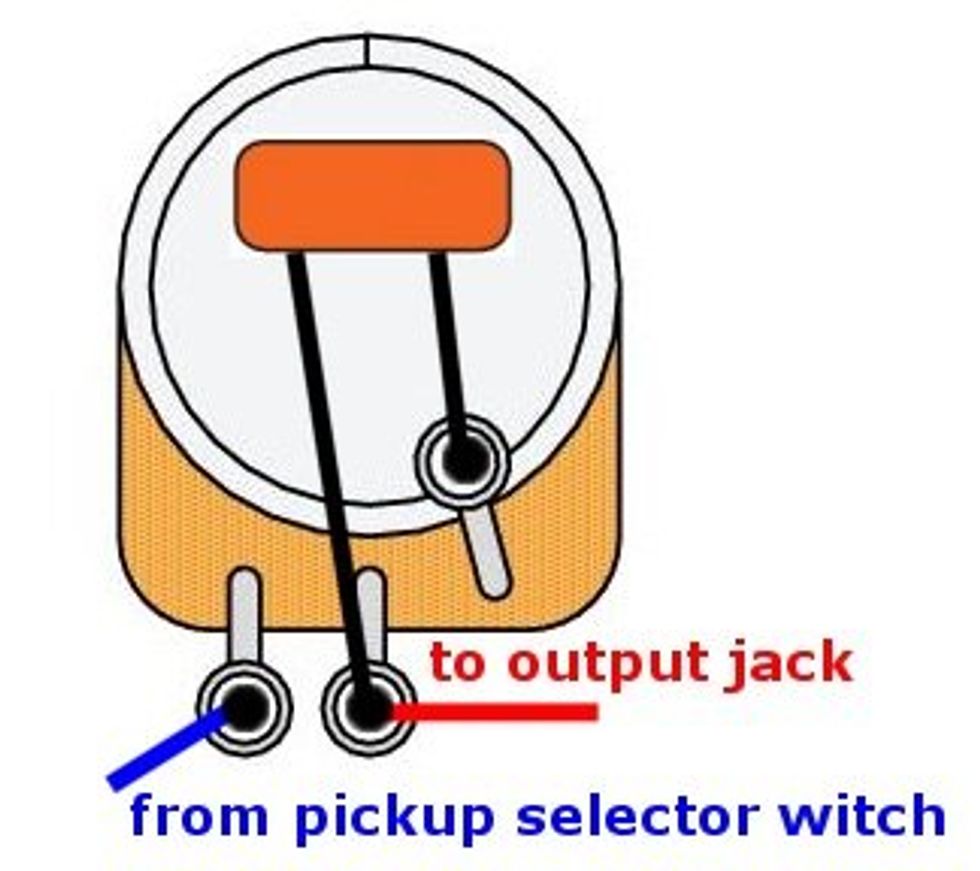

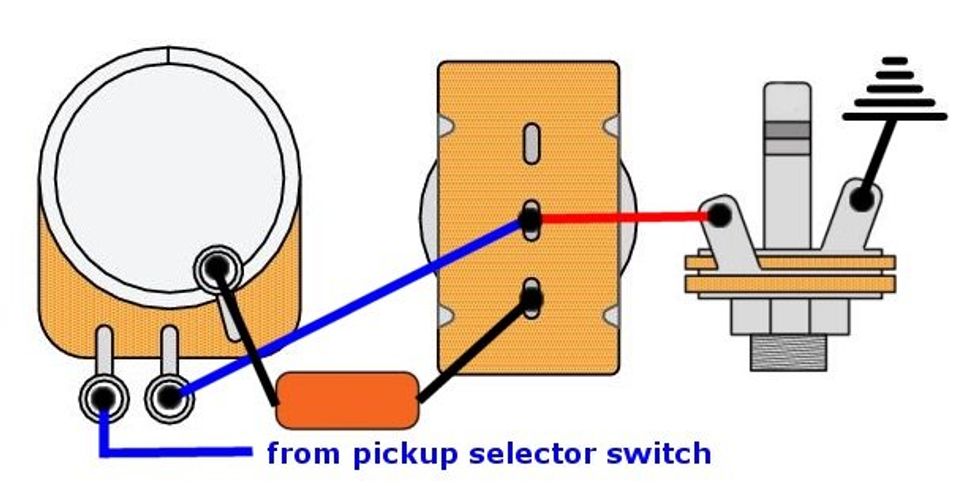

The mod itself is relatively easy. Simply unsolder your tone pot and then connect the new parts as shown in the diagram. (Note that the resistor is soldered in series with the 0.022 μF cap.) The rest of the Strat wiring, including the volume pot, stays standard.

Fender's Greasebucket circuit in all its glory. (Seymour Duncan and the stylized S are registered trademarks of Seymour Duncan Pickups.)

This wiring diagram comes courtesy of Seymour Duncan Pickups and is used with permission.

This type of band-pass filter only allows certain frequencies to pass through, while others are blocked. The standard tone circuit in the Strat is called a variable low-pass filter (aka a "treble-cut filter"), which allows only the low frequencies to pass through while the high frequencies get sent to ground via the tone cap.

The Greasebucket's bandpass filter is a combination of a high-pass and a low-pass filter. This circuit is designed to cut high frequencies without "adding" bass. Mostly it has to do with that 4.7 kΩ resistor wired in series with the pot, which prevents the value from reaching zero. You can get a similar effect by simply not turning the Strat's standard tone control all the way down. The additional cap on the wiper of the Greasebucket circuit complicates things a bit, because together with the pickups, it forms an RLC circuit (a resonant circuit comprising a resistor, an inductor, and a capacitor), but that's outside the scope of this column. But the Greasebucket has its own special sound, and I can only encourage everyone to try it. You'll be surprised at its flexibility and tone.

If you're adventurous, you can personalize the Greasebucket circuit with additional mods. For example, you can try different tone-cap values and materials. The 0.022 μF cap connected to the tone control is the standard configuration we all know from our Strat's tone control. But, as we've discussed several times in previous columns, there are tons of alternatives. You can try other values from 2200 pF up to 0.1 μF, and also different types of new, used, or new-old-stock (NOS) caps—such as metal film, film, paper in oil, waxed paper, and silver mica. Your choices are virtually unlimited.

We'll discuss more Strat mods—such as the Fender S-1 switching system—in the coming months, so stay tuned.

[Updated 9/24/21]