Sub Pop’s seminal grunge pioneers Mark Arm and Steve Turner detail their stalwart Gretsch and Guild sidekicks before divulging their favorite fuzz circuits—and go-to modern copies—and showcasing pedalboards that reincarnate their guitar tone into grimy, filthy, and feral wooly mammoths.

Universe: “Super Fuzz or Big Muff?”

Mudhoney: “Both!”

What else would you expect from a band that titled their mischievously visceral ’88 debut EP after both pedals (Superfuzz Bigmuff)?

Formed in the late ’80s by guitarists Mark Arm and Steve Turner after the dissolution of their band Green River (which included future Mother Love Bone and Pearl Jam cofounders Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard), Mudhoney long ago solidified themselves as the Seattle scene’s big brothers and tightest pack. Through their 11 LPs, five EPs, and six live albums, Mudhoney has routinely diversified and further defined their eccentric brand of raucous, aggressive, unfiltered rock ’n’ roll. Possibly more impressive than the band’s wide influence and devoted authenticity is the foursome’s bond. Drummer Dan Peters and bassist Matt Lukin (also a founding member of the Melvins) were the rhythmic bedrock for Arm and Turner’s exploding-M-80 tones since the beginning. (Arm and Turner have been friends since high school and have been playing off each other since then.) But Lukin left the band in 2001 because tour life became too much, and Guy Maddison has been thundering ever since. To see a group’s career that’s pushing past 35 years and only have one member swap is as inspirational as it is baffling. How?!

“We like each other a lot. We get along. We love what we’re doing,” remarks Arm. “Why stop, even if no one gives a shit?”

Friendship matters to Arm and Turner, but gear isn’t a concern unless it points them in one direction—east. More specifically, toward Detroit, Michigan. And even more specifically, to the Stooges. Both namecheck the livewire band and their raw power several times in our Rig Rundown. However, in a 2018 interview with Premier Guitar, they acknowledged regenerating sounds that echo influences from Neil Young and the Byrds to Devo and the Dead Kennedys. But after chasing “I-Wanna-Be-Your-Dog” sizzle, what else leads them to the gear they use? Has that mentality changed since the late ’80s?

“If you think about the aesthetics of where we come from—garage punk, and punk rock in general—a lot of it was made with cheap gear, and a lot of it was reclaiming gear that guitarists had kind of dismissed as garbage. Like the Mustang. That was my ultimate guitar back when I was a kid, but it was poo-pooed when I finally got one. I could get them for $150. The Danelectro and Silvertone amps were kind of high-rated garbage when we were getting into them. We based a lot of our sound on cheap gear, so it makes sense to me that I still buy the cheap gear,” concluded Turner.

They’re still pragmatic about their setups, preferring equipment that’s familiar and reliable. Where they chase the dragon is in stompboxes. Turner trusts the Big Muff (his favorite iteration is from the mid-’80s), while Arm’s torrid tone burns with a Super Fuzz clone. However, both have additional hot-sauce stompboxes and other effects on their pedalboards that are being auditioned trial by fire.

Hours before Mudhoney’s headlining set at Nashville’s Basement East, Arm and Turner brought PG’s Chris Kies onstage to catalog their setups. Turner started the party by talking about a pair of guitars—his battle-tested late-’60s Guild Starfire IV and a recently-acquired Fender Gold Foil Jazzmaster before kicking on his Big Muff and other pedals that unlocked Dante’s inferno. Then, Arm joined the fun by showing off his Gretsch Vintage Select ’59 Duo Jet that eventually gets pulverized by three different fuzzes.

Beggar’s Banquet

Turner has always gravitated towards the Island of Misfit Toys, and says he was intrigued when he saw Fender’s Gold Foil Jazzmaster. “When we recorded Plastic Eternity, I used a Bigsby, but I don’t own a guitar with one. So, when Fender released this model I demanded one. I actually begged for one,” he jokes. “It’s essentially a knockoff of an old Silvertone, and I think it’s hilarious for Fender to do.” He’s enjoyed getting to know the instrument, whose bigger neck and brighter pickups offer an alternative flavor to his Guild. In recent years, Turner has dialed back his string gauges and currently goes with Dunlop Heavy Core strings (.010–.048). Both his guitars are always in standard tuning.

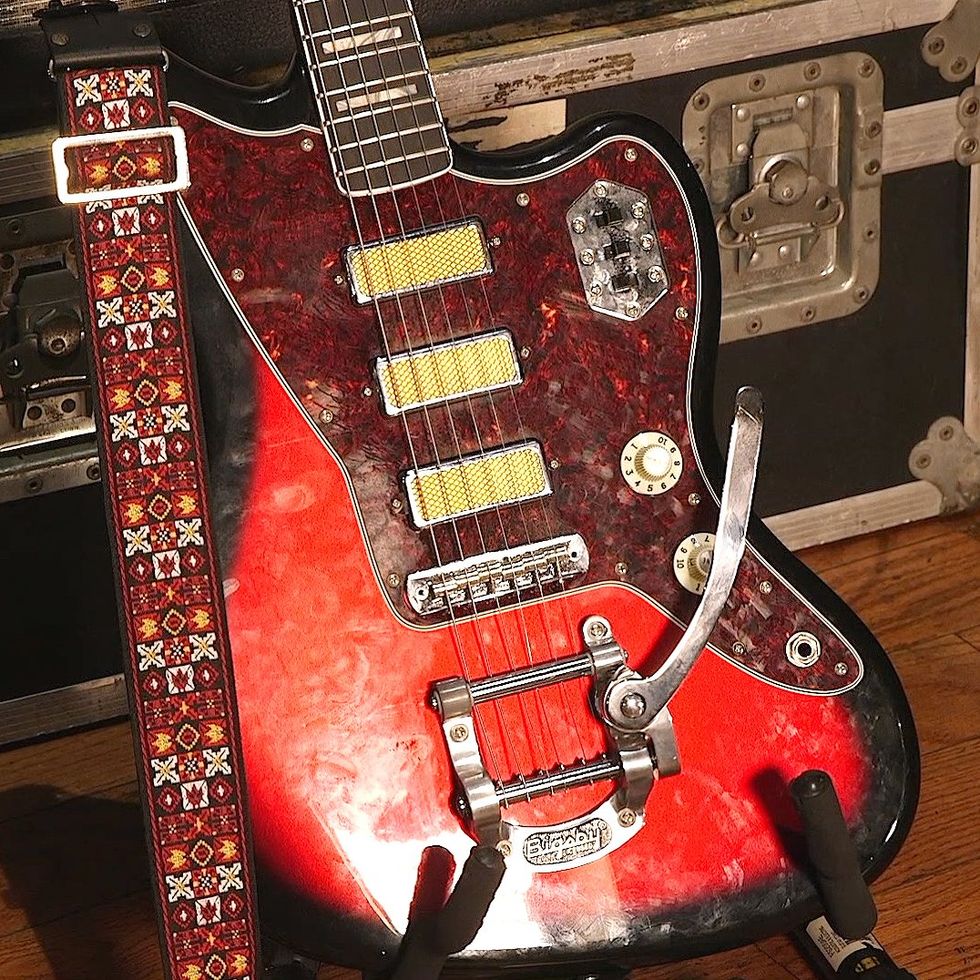

Red Rider

The past two decades, Turner has mainly been playing a pair of Guild Starfire IVs. One is from 1967 and the other is a ’68. He doesn’t know which one is which, but believes this one to be the “newer” one. He likes it more because “it’s a little heavier, it sounds woodier, it’s got better tuning pegs, and it’s got a slightly bigger neck.” He never thought the semi-hollow would work with Mudhoney because of the massive layers of fuzz he puts on his guitars, but after taking it to band practice as a “joke” and dealing with the “quick learning curve” to EQ his gear and change where he stands in relation to his amp, he’s been on cruise control with the Starfire IV.

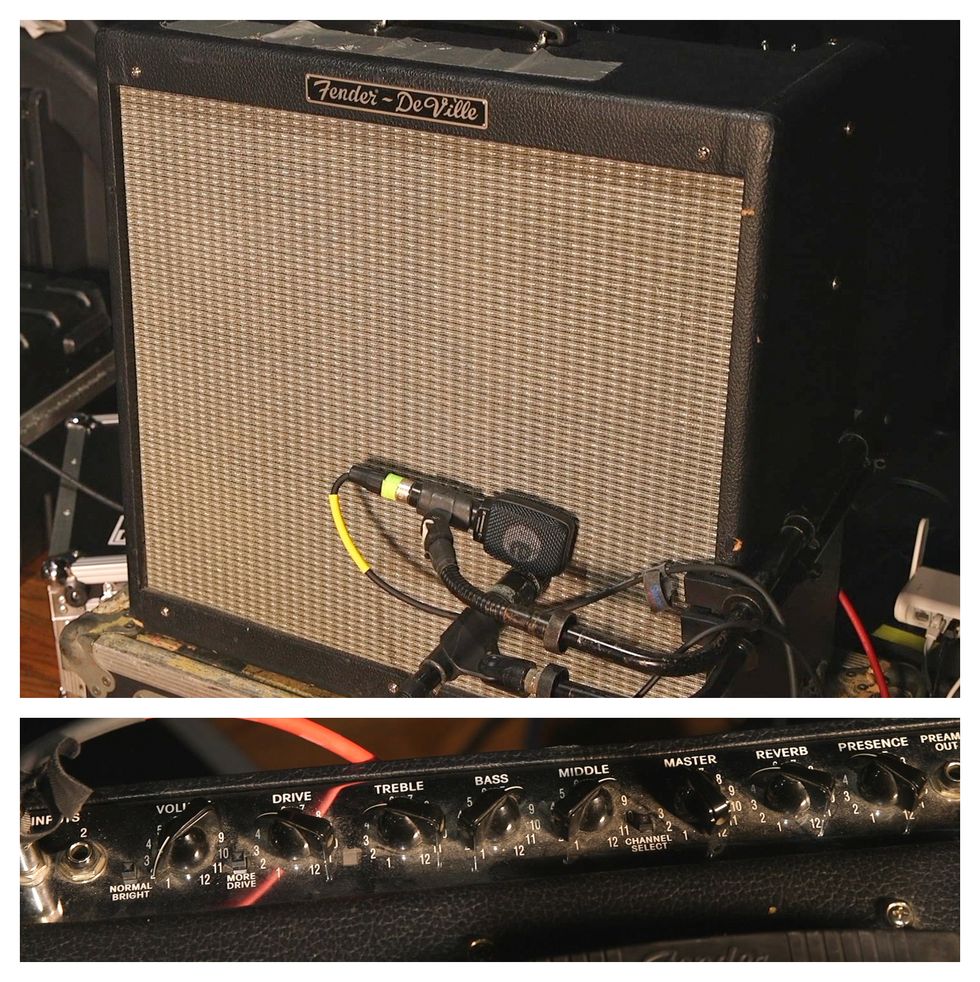

Couple DeVille

When Mudhoney started, Turner had a 1965 Super Reverb. He still owns that amp, but says he keeps it at home. The closest amp to that benchmark he’s encountered and plugged into is this stock Fender Hot Rod DeVille III 4x10 combo.

Steve Turner’s Pedalboard

This is the fanciest pedalboard Steve Turner has ever brought on tour. His pal and owner of Hank’s Music Exchange in Portland wired this up for him. The one thing Turner requested of Hank was that he put the MXR Micro Amp, VOX V847A Wah, and Electro-Harmonix Little Big Muff Pi at the front of the chain. Turner likes pushing the amp with the MXR and then juicing the Muff with it, too. He prefers the wah earlier in the chain, so it has as much bite as possible. “I want it to sound like a Stooges record where the wah is twice as loud as everything else!”

Turner told PG in 2018 that his favorite modern Muff is the EHX Nano edition, which he says best approximates his pinnacle pedal (a mid-’80s Big Muff). “My favorite is the Nano, the cheapest ones they make. They’re like 60 dollars or something. They’re almost disposable—because they do break. But oh, well. Buy another one! Going off memory and feel, to me the Nano sounds the most like that. In the studio, I bring in a whole bunch [of other fuzzes], but then sometimes I just get lost trying to fix something that doesn’t really need to be fixed, you know what I mean?”

Speaking of fuzz, Turner was experimenting with the Before finding a friend in Gretsches, Arm had been playing SGs, Jaguars, Hagstroms, and others. He acquired his 1991 Gretsch G6129T-59 Vintage Select ’59 Silver Jet reissue because he wanted to look like Billy Zoom. This black stallion G6128T-59 Vintage Select ’59 Duo Jet is a more recent reissue he prefers for its chambered body, which is lighter and more resonant. After reading the Black Sabbath: Symptom of the Universe biography by Mick Wall where he learned that Iommi played light strings, he made the move from Ernie Ball Skinny Top Heavy Bottom Slinkys (.010–.052) down to Ernie Ball Super Slinkys (.009–.042). while pursuing the ’60s Fuzzrite nastiness felt on the Stooges’ early rippers. Signal swayers include a Strymon Flint and a vintage script-logo MXR Phase 90. And an Ibanez TS9DX Turbo Tube Screamer joined the bunch when gifted from former Green River bandmate Stone Gossard. A Peterson Stomp Classic Strobotuner keeps his guitars in check and a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus ignites his stomps.

A Goodie!

Before finding a friend in Gretsches, Arm had been playing SGs, Jaguars, Hagstroms, and others. He acquired his 1991 Gretsch G6129T-59 Vintage Select ’59 Silver Jet reissue because he wanted to look like Billy Zoom. This black stallion G6128T-59 Vintage Select ’59 Duo Jet is a more recent reissue he prefers for its chambered body, which is lighter and more resonant. After reading the Black Sabbath: Symptom of the Universe biography by Mick Wall where he learned that Iommi played light strings, he made the move from Ernie Ball Skinny Top Heavy Bottom Slinkys (.010–.052) down to Ernie Ball Super Slinkys (.009–.042).

“Slide in Standard Tuning Sounds Like Shit”

Turner admits that the band’s earliest work features some earache moments where he played slide on his Hagstrom in standard. He now puts the ’60s Hagstrom III (with a Filter’Tron neck pickup) in a custom open-A tuning for slide playing.

Set It and Forget It

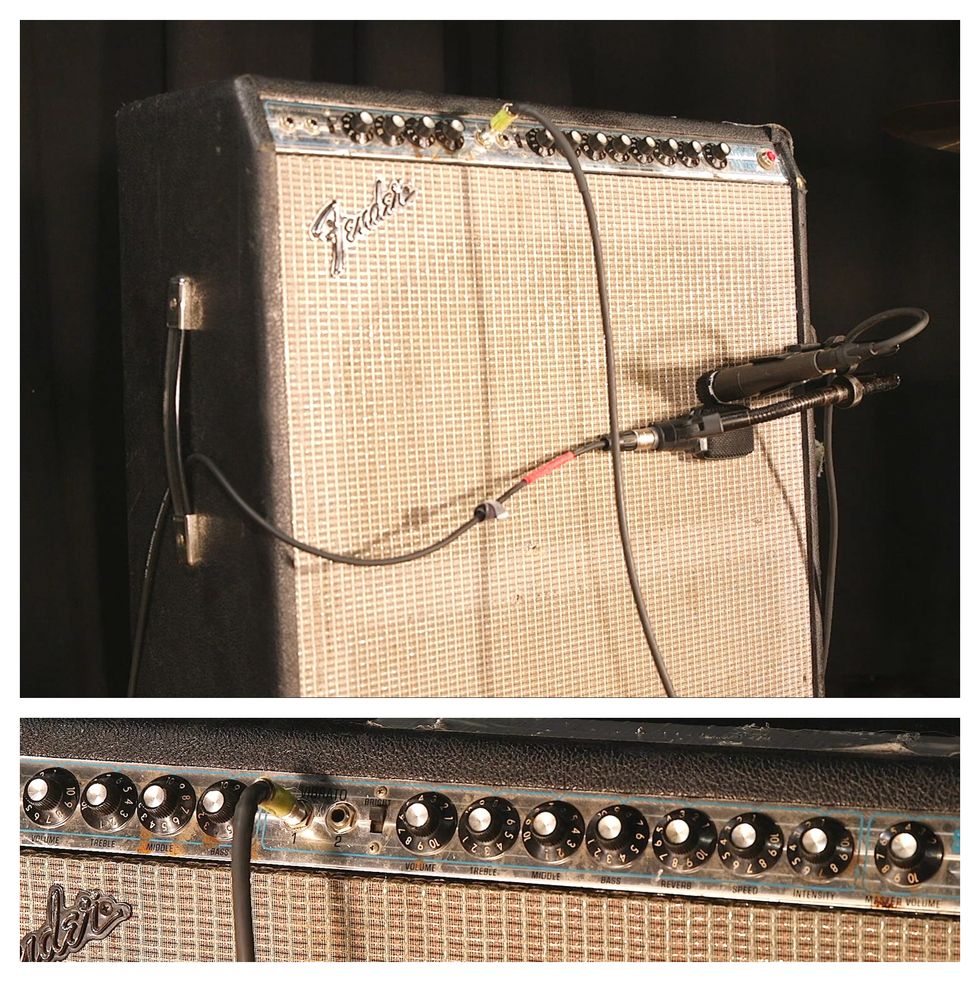

Arm bought this ’70s Fender Super Six Reverb years ago and hasn’t worried about touring amps ever since. The 100-watt combo has a sextet of 10" speakers, a quad of 6L6 power tubes, and a quintet of 12AX7 preamp tubes.

Mark Arm’s Pedalboard

Arm isn’t a gearhead, but he definitely loves fuzz. His current pedal playground includes three variants—an EarthQuaker Devices Life Pedal V3 octave/distortion/booster, an Ibanez Soundtank FZ5 60’s Fuzz (housed in the gray box), and a Stromer Mutroniks Superfuzz.

Arm on the Ibanez: “In the ’90s, one of the boxes that I landed on that I liked most was this Ibanez Soundtank-series 60’s Fuzz. I think they only made it for a year or two, because they’re made of this cheap plastic—they look like a little black Volkswagen Beetle—and they just break. Anytime I’d find one in a music shop, I’d just buy it and have a buddy put the guts into a metal box.”

Then, Arm recounts when, after a few shows during an early Mudhoney tour with Sonic Youth, Lee Ranaldo asked him, “What are you going for?” Mark responded: “Ideally, it’d be like ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ where Ron Asheton plays the opening chords, and it just hangs there and breaks up. I want that sound, all the time.” That sound Arm was approximating was coming from a Super Fuzz. His current copy for the vintage eviscerator is the Stromer Mutroniks edition. The remaining pedals are all from Portland’s Catalinbread: Epoch Boost preamp/buffer, Belle Epoch tape echo, Valcoder tremolo, and Sabbra Cadabra overdrive. A Peterson Stomp Classic Strobotuner puts Arm’s guitars in the sweet spot.

G6128T-59 Vintage Select ’59 Duo Jet

Ibanez TS9DX Turbo Tube Screamer

Peterson Stomp Classic Strobotuner

EarthQuaker Devices Life Pedal V3 octave/distortion/booster

Dunlop Heavy Core Strings (.010–.048)

![Fontaines D.C. Rig Rundown [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/image.jpg?id=60290466&width=1245&height=700&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: Umphrey’s McGee [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=60219771&width=1245&height=700&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)