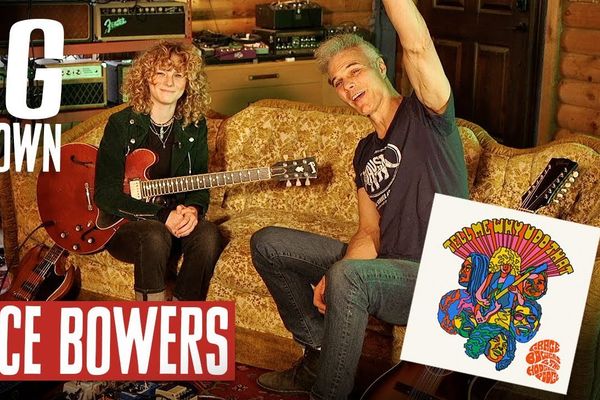

Find out what rocks the world of the self-taught clinician, loop master, and former Asia guitarist.

In a world where everything is amazing and nobody’s happy, I was very happy when I was told I’d be interviewing my guitar teacher. I’d never met Guthrie Govan, but for the past ten years I’ve been studying his lessons in Guitar Techniques magazine. Guitar Techniques calls him “the world’s most outrageous guitarist,” and anybody who has studied his columns will swear to this fact. Govan’s playing is amazing, but he has the rare gift of being a super-effective teacher. Some of the greatest guitar players on the planet are rotten teachers, so what he gives to the guitar community is not lost on me.

Not only does he take complicated music theory concepts and make them understandable to slow kids like me, but he also transcribes and interprets the work of the masters so we lesser players can get it. He can go from Albert King to Allan Holdsworth in a heartbeat—and then show up to his own gigs and be his unadulterated self.

If you’re wondering how Govan got where he is today, here’s the scoop: He replaced Steve Howe in the prog-rock band Asia from 2001 to 2006, he teaches guitar clinics all over the place, he is the author of two books, Creative Guitar 1: Cutting Edge Techniques and Creative Guitar 2: Advanced Techniques, and he is currently prepping for a follow-up to his first solo record Erotic Cakes. You could call Govan “a guitar player’s guitar player,” but there’s a lot more going on with him than that. My time spent with him revealed an artist searching for something deeper than creating a guitar chops record. For certain, he was blessed with having achieved technical virtuosity at an early age (his first gig was at age five), but today he’s on a spiritual path to use his talents to not only speak to guitar players, but to lovers of fine music as well.

What have you been doing lately?

Trying to get my next album done. Things keep getting in the way, which is nice. In this economic climate, being too busy is not a problem anybody should be complaining about. My policy at the moment is to say “yes” to everything—do as much work as possible now, and when I think I can feed myself for a few months, start saying “no” to everything. I’ll just lock myself in a room, draw the curtains, and then try to do the album in one go. I want to go from the initial writing stage to, “Okay, now it’s ready to put live drums on it.” I just want to do it all in one period. The next album should be a snapshot of where I was in my life.

What’s getting in the way?

I’ve been keeping busy doing sample replays. The dance music guys will make a demo and take four bars of a James Brown loop or something like that. A lot of it is old disco stuff or The Red Hot Chili Peppers. When it’s time to release the record they realize that they can’t use the actual loop from the original record for legal reasons or financial reasons. There are companies who recreate those loops and get other musicians to try and get the same tones. They basically try to come up with a facsimile of that loop.

So they bring you in to replicate the guitar parts?

Yeah, I’ve done a lot of guitar and a bit of bass. It’s been good for my disco bass playing. [Laughing] I pretend to be a bass player. I’ve inadvertently found myself playing on Dizzee Rascal’s latest album in a sample replay capacity. He’s the foremost rapper in the UK. He was approached by the BBC. They did a thing called The Electric Proms, where they take popular artists and try to put them in an unusual context. The year before they had Oasis playing with an orchestra. For this they wanted Dizzee the rapper to play with a rock band and a choir. So I ended up in this band for a televised gig with a twenty-piece string section. There were horns, a male voice choir, and then me just shredding and playing acoustic! I played about five minutes of every musical style known to man. It was a really fun gig. I think Dizzee liked it as well and saw real potential in doing the rap thing a little bit differently. So, I’ve been gigging a lot with him lately. It’s like missionary work. [laughing]

What’s the deal with you and the band Asia?

Photo by Harmony Gerber. |

The situation was, everyone else in that band lived in the LA area and I lived near London, so we’d get one-off gigs at festivals or casinos. Every time there was a gig, I would have to fly for eleven hours from London to LA to rehearse for the gig and get all the gear sorted, then maybe to fly to Philadelphia to do the gig. Then fly back to LA so I could cash in on my return ticket to get back to London. It was a week out of my life and a world of jet lag, and another week of feeling ill once I got home. I just couldn’t justify doing it. It was killing me. I loved the guys to death. I really enjoyed playing with them, but in the end I had to say, “You should get an American guy who will appreciate this gig, rather than the guy who is doing it out of love or whatever.” Those guys have been working with Mitch Perry, so I think that’s going to be a good thing.

Have you done any tracking for the new record yet?

Not really. I have enough material to make a new album, but I don’t want to do it that way.

You want to do it all in one big shot.

Yeah. I’ve tried one way of doing an album, which is using some tunes that I wrote nearly twenty years ago, some tunes I wrote ten years ago, and a couple that I wrote fairly recently. It’s this big sprawling conglomeration of things that I’ve done over the years. I know what it’s like to make an album that sounds like that. I want to explore doing it the opposite way so I can learn something about the whole working process. It’s more about continuity and just being able to come up with everything in one period of time. I find that if you can lock yourself away from the rest of the world just for a few days, gradually you start to go mad in all the right ways. You start to feel more creative and then you’re surprised at what comes out. So, rather than planning what kind of album it’s going to be, the plan is to lock myself away, go slightly mad and see what comes out.

In your columns you’ve transcribed everyone from Robben Ford to Yngwie. How does that inform your personal style?

The core of what I do is being a kid and listening to a lot of Cream-era Clapton, Hendrix, Alex Harvey Band and stuff like that. It was working out Beatles chord progressions, Clapton blues licks or whatever. It’s always been about using my ears. I’ve never had a guitar lesson in my life.

Not one lesson?

Yeah. I found that in general I’ve always learned the sound of something first, then gone to the library to read up on things and find out what the name was for that sound. When I was a kid I remember having one of the Joe Pass Virtuoso albums and trying to work out some esoteric harmony that I never heard on a Chuck Berry or Beatles album: “What the hell are these chords? I don’t know what they’re called!” So I would try to find a shape that sounds like that. Then you associate the shape with that sound. Then six months later you’re reading about altered chords in a library book: “I knew that! I just didn’t know there was a word for it!” That way you can incorporate new stuff into the way you play more naturally. I think if you sit down with a scale book and say, “Today I’m going to conquer the Lydian Dominant,” you’ll end up knowing all these shapes and playing them at a certain speed. You still have to assimilate that into the more subconscious side of how you play. How do you make that feel as natural as the blues licks that come so easily to most of us?

It’s tough when you learn something that way round. It’s just a cold morsel of theory. I’ve seen so many people over the years where you give them a minor pentatonic shape and they will play beautiful well-phrased musical stuff, because they don’t have to think about it anymore. It’s imprinted on them on some very basic level. So then you say, “Can you play modally or put in some chromatic notes?” Suddenly the musical player isn’t there anymore. You can hear that they’re thinking too hard to play anything that’s meaningful. So I’m quite glad I learned the other way around.

You found a context for the sounds first as opposed to starting with an exercise or a pattern of notes?

Yeah. If you think you’ve learned the scale, can you sing it? Can you scat it without having a guitar there or without having a shape to guide you? If you can’t sing it or feel it, then you don’t really own that scale. You just memorized the short cut to those notes. The process has to be imagining some music in your head, then being able to play what you hear in your head by ear.

What was your big guitar epiphany when you were younger?

It was figuring out that a lot of blues players use the same blues boxes and the same licks, but I know after one note whether it’s Freddy King, Albert King or B.B. King. It’s the same note, but I knew which guy it is. It’s about the way you play and the tone that compliments what you’re trying to say best. Sometimes the wrong note played with the right tone and the right attack works better than perfect notes played with apathy. I spent a lot of time trying to make my one guitar and my one amp sound like all these different players. I’m really glad I spent time doing that.

The other epiphany was Jimi Hendrix. There was no division between lead playing and chord playing. “Little Wing” has a rhythm part but there’s melody buried in it. The other extreme was “All Along The Watch Tower,” which is one of my favorite moments. It’s very disciplined, organized Jimi. He composed the solo in all these different sections and one of them is “Oh, you’re inventing funk rhythm guitar playing and you’re doing it in the solo!” That blur between those two camps I thought was a really interesting thing. It really helped a lot with my rhythm playing and the idea that you don’t have to be stuck in a block.

Guthrie performs to a packed house in Boston with the Jon Finn Group. His recent Boston visit included clinics and seminars at Berklee College of Music. Photo by JR Terri. |

Frank Zappa was an epiphany with the way he phrased. I just got it one day. For a while I loved everything about the music, but I wasn’t quite sure about the guitar playing: “Is this guy a genius or can he not really play?” Then I got it one day. He’s phrasing like people talk, which is why it looks so horrendous when you see it written down. It’s hard to quantize that stuff, but we all phrase like that when we speak. There’s a floating tempo when we speak, so it makes sense when you hear it. When you put it behind any kind of pulse it becomes a really intriguing thing to listen to.

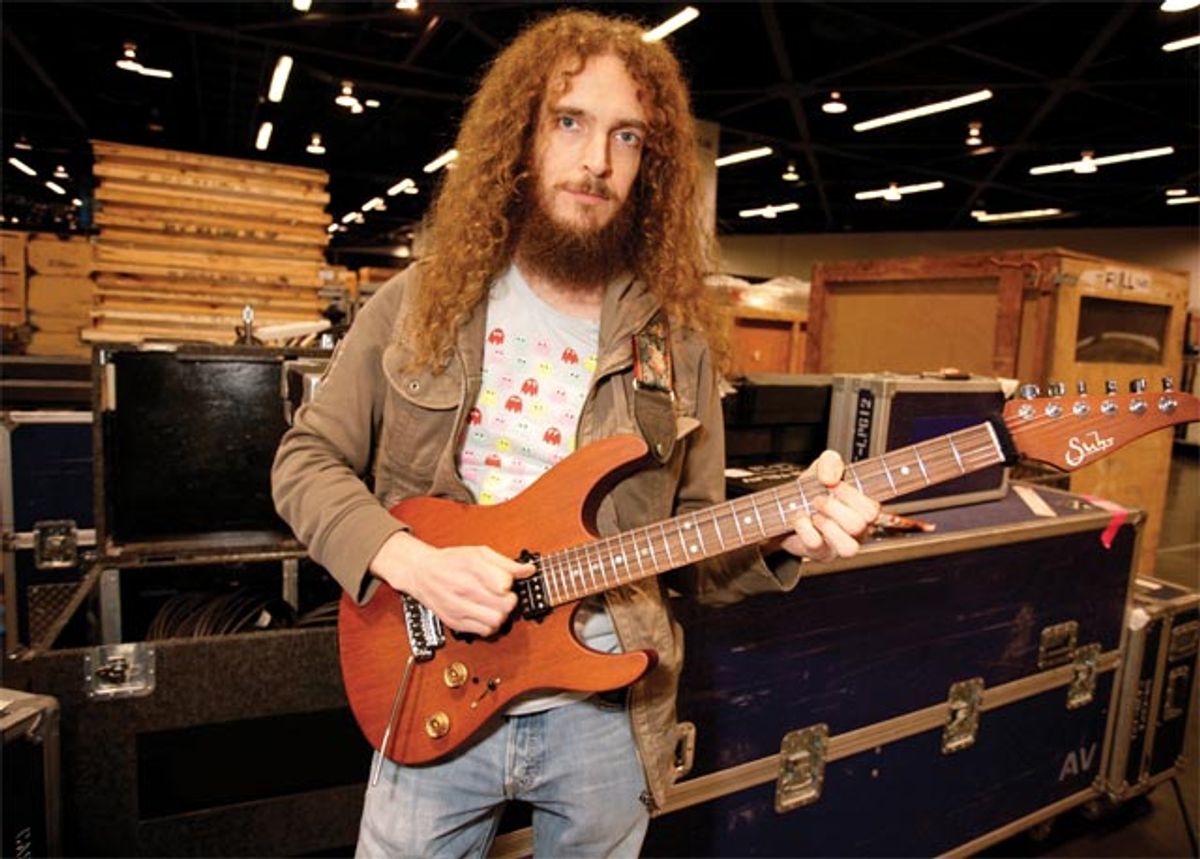

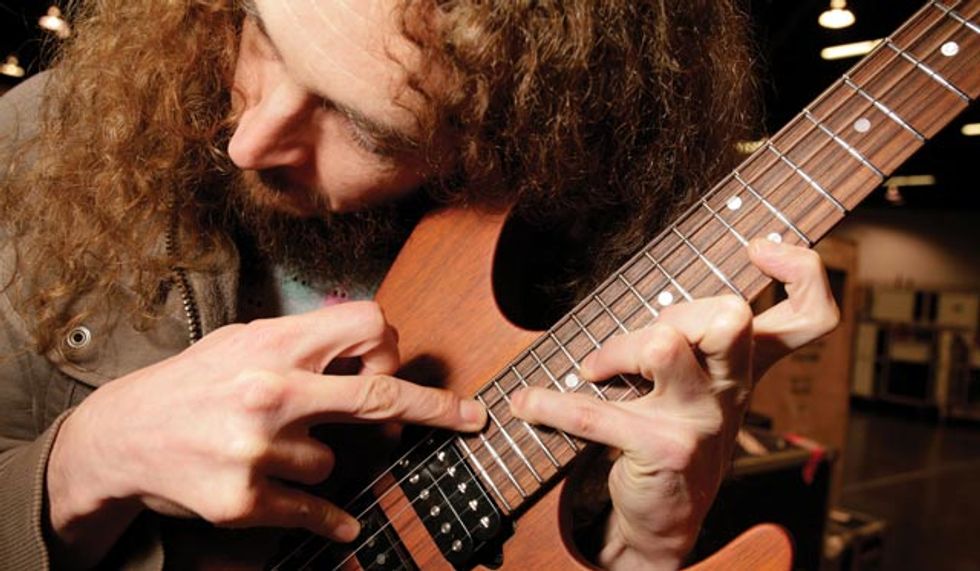

What’s your favorite guitar right now?

I guess I have to say my signature guitar. [laughing] If I helped design it and I still didn’t like it, there would be something wrong. It’s a mahogany beast made by Suhr. There’s a new version of it that just came out. It has a mahogany neck, a set neck joint, a mahogany body, and pretty much no finish—it’s pretty much one lump of resonant tree. It’s got big frets and a pau ferro fretboard, which I think is Bolivian rosewood. It’s harder than other rosewoods. It has moderate output pickups, not too loud. If the pickups get too meaty, you lose some of the character of the guitar and that’s a shame.

It’s two Suhr humbuckers with a single-coil in the middle. The push-push switch is set so you can get different flavors, so it’s something of a Tele. You can get the neck coil and the bridge coil. You can get a Mark Knopler sound or a Stevie Ray sound. I was raised on old-style amps. An amp with four channels is a luxury I’ve never known, so I’ve always tried to do things with the volume knob. There’s a lot of new sounds in any guitar if you explore what the volume knob does. The switch was born out of a desire to be able to set the volume knob to that perfect sweet spot where you can get a clean tone through an overdriven amp. It’s just loud enough and just clean enough, and then it remembers that when you switch to the solo sound. It’s a simple button you can push on the guitar. It’s the bridge pickup straight into the output jack of the guitar for maximum meat. Then when you push the button again, the guitar remembers the volume knob being in your favorite place. I love that.

It’s seems like a versatile guitar but would sound a little dark.

A lot of people think that. They think mahogany is going to sound like mud, but not necessarily. Mahogany has a certain focus in the midrange and a certain honk, but everything else is in there as well. What I’ve discovered talking to the Shur guys, who know a lot about wood voodoo, is that the most balanced sound you can get is a basswood body, a maple top, maple neck, and some kind of dense rosewood fingerboard. I just like the mahogany honk. My other favorite guitar is the first electric guitar I ever had, which was the Gibson SG. Guitars that are built that way feel right to me.

What is it about Cornford amps that you like so much?

The same thing that other people sometimes don’t like: they’re very honest amps. Whatever goes into that amp is what will come out louder. If you compare and contrast that with something like a Triple Rectifier, that’s an amp with a lot of personality. You can get a number of players with a number of different guitars and plug them into that amp. To some extent they will all sound similar, because the amp is doing quite a lot of the work. Cornfords kind of do none of the work. They just amplify it. The basic idea of the amp is translating every little detail of the way you hit the notes. So if you’re a shredder and there are maybe tiny weaknesses in your technique, the Cornford will bring them out and make you feel bad about your playing. If you come from a blues background and you play one note in a million different ways, it’s a really rewarding amp because you get a million different sounds coming back at you. It’s really responsive.

I noticed playing the Cornford Roadhouse that if your right hand muting is together, you’re going to know about it.

I like the MK50H II. It has a dedicated clean channel, which is something of a departure for Cornford. Cornford is pretty much in love with the dirt. They’re going for the “brown sound.” Clean sounds are someone else’s problem. You do it with your volume knob if you need it. Because of the dedicated clean channel on the MK50H II, I can take it to absolutely any gig and depend on it to give me the tone I want at whatever volume I want. It’s quite nice that those amps have two master volumes so you can switch between them. It also has two flavors of dirty, so it’s like having a Tube Screamer on the floor but it’s in the amp.

Are you a fan of effects?

Sometimes. It depends on the situation. I do a fusion gig at home once a week and I love bringing in envelope filters and ring modulators and all my childish toys. When I was playing with Asia, my whole pedal board would be a volume pedal, a wah, maybe a chorus in the effects loop and that was it. I’ve discovered if you drench what you’re playing in lots of signal processing, it sounds great in rehearsal or your bedroom, but people in the back row of the hockey arena or whatever are not going to hear what you’re playing. I’d rather go for the unforgiving sound in the hope that it will reach the back of the room and there will be some clarity there.

Photo by Harmony Gerber |

I love the Analog Man Chorus, which I guess is modeled on a Kurt Cobain kind of chorus. If you turn the speed up you get this nice Leslie effect. If you turn the depth up too much you get John Scofield, which is pleasing. The Xotic effects Robotalk is my new toy. I’ve always loved envelope filters. The new Robotalk has two versions of the same thing, where you can set your two favorite filter sounds and switch between them or combine them. You can control the output of the filter, which is a good thing as well.

What kind of music do you listen to for pleasure?

Have you heard stuff from Squarepusher? You might like it or it may horrify you. It’s guys using the tools that dance music guys would use. Instead of trying to come up with something that will work on a dance floor, they’re being more Stravinsky about it: “Let’s do something crazy with these tools.” I love listening to that stuff because I have no idea how it’s done. If I listen to another guitar player, I can generally guess within reason what they’re doing, and what fret they’re doing it on, and where they learned that lick. I can generally give you the genealogy of the lick and who did it first. It’s nice to know all that, but if you want to know what other people hear when they listen to music, listen to music you don’t understand. The electronic thing for me is that. It’s quite nice not to know anything about the mechanics of how this music was made. It’s pure sound.

And it doesn’t come from a guitar-centric place. Right. The other thing is that Indian music is very intriguing. It’s very frightening. It’s like this precipice you can peer over and be terrified by it. I know that I could spend the rest of my life just devoting it to Indian music, and I still wouldn’t be very good at it. It’s good to blow your own mind occasionally.

Ever had a bad audition?

| GUTHRIE'S GEARBOX Guitar: Suhr Guthrie Govan Signature Model Amplifier: Cornford MK50H II Effects: Analog Man Chorus, Xotic Effects Robotalk 2 |

Yes. There was one audition that didn’t go well. It was with a bunch of friends; we auditioned as a whole band. It was for Imogen Heap, who is wonderful. This was just before anyone had heard of her. She was this underground character who was going to be big. We went along and auditioned as a bunch of friends. It was all going swimmingly until Imogen says to the bass player, “Can you play an F sharp?” He couldn’t find one. That’s how much of an ear player he was. He didn’t know the names of any notes. We knew at that moment it was not going to go well. [laughing]

guthriegovan.co.uk