We musicians love analyzing our heroes’ gear. We pore over tomes and fan-generated websites dedicated to chronicling the instruments, amps, and effects used by rock’s most celebrated artists—and not just what they used, but the when, where, how, why, and with whom of it, too. In the case of out-and-out icons, a single writer will author multiple full-color volumes inventorying everything from the gear itself on down to minutiae such as cosmetic changes and original purchase receipts. And if the hero’s big enough, the gear knowledge even spills over to the general public: For instance, plenty of everyday folks could tell you Hendrix played a Stratocaster, or that Page blasted through Marshall stacks during Zep’s heyday.

But rather than revisit what’s already been done in that regard, we thought it would be both interesting and enlightening to take a look at the gear of influential rockers from a slightly different vantage point. Instead of talking about stuff like when and why Lennon installed a Bigsby on his ’58 Rickenbacker 325 Capri, or whether Keith Richards’ famous ’53 Tele was used on such-and-such track, we decided it would be telling to take a look at broader patterns in the gear trends within eras and movements. For the sake of simplicity, the most logical route seemed to be breaking it down by decade. And for digestibility and space, we also limited each decade to two guitars, two amps, and, where applicable, a smattering of effects we feel epitomize the era.

Now, before you balk, let’s just get it out of the way that it’s more than painfully obvious to any rational gear nut that, as rock ’n’ roll evolved beyond it’s already-complex 1950s roots, it only got more complicated—and huge. There’s simply no way a couple of 6-strings and amps, or any reasonable sampling of outboard gear, could capture the breadth of aural exploration in any given year, let alone a decade. Yet, as with aerial views of important landmarks or archeological sites, we contend that the exercise is worthwhile for reasons beyond enjoyment, nostalgia, and friendly bickering. While the beginnings and endings (and later resurgences) of movements rarely coincide with the base-10 reset mark in our calendar system, as a society we’ve come to view decades in a set of generalizations that can be just as handy here as they can for discussions about everything from politics to fashion.

As we found when we dug in to compile this list, we’re sure you’ll notice omissions or oversights that perhaps seem egregious, maybe even sacrilegious. As with everything, we welcome your thoughts on the matter (as if we have a choice!). But we also encourage you to keep in mind that what we offer up here is our best shot at a concise record of gear that represents the prime movers and shakers in rock music during the indicated time periods. Given how genres are forever splintering into infinitesimally smaller niches, certainly many players will differ in their view of how far a path can diverge from those blazed by Chuck Berry, Elvis, the Beatles, or Hendrix and still qualify as a sprouting bud on a twig of the rock ’n’ roll family tree. Hopefully the conversations inspired here will open doors and broaden some horizons for you as much as they already have for us.

1950s: The Birth of Rock ’n’ Roll

The further one gets from the advent of rock, the easier it is to mistakenly simplify it as boiling down to Chuck Berry and Elvis. But then as now, the truth is much more complicated. An amalgam of African American blues, R&B, doo-wop, and gospel music mixed with white hillbilly music, rock was made possible by technology (point-to-point-wired vacuum-tube circuits) conceived in the World War II industrial complex combined with jazz-age hollowbody guitar lutherie of the sort mastered by fine builders like Gretsch and Gibson.

Prime guitar movers: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Scotty Moore, Billy Haley, Bo Diddley, Gene Vincent, Cliff Gallup, Duane Eddy, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Gibson ES-335

The musical and cultural impact of Chuck Berry and his Gibson ES-335 (he also favored a Gibson ES-350T) can hardly be overestimated. These guitars powered galvanizing live favorites like “Maybelline” (1955), “Roll over Beethoven” (1956), and “Johnny B. Goode” (1958), and had a huge influence on later greats such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Gibson ES-295

On landmark recordings such as “Don’t Be Cruel” (1956), “Hound Dog” (also 1956), and “Jailhouse Rock” (1957), the woody, ringing tones Scotty Moore conjured on his Gibson ES-295 and 1954 L5 CESN resonated around the world and ushered in the reign of the King of Rock ’n’ Roll, Elvis Presley.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Magnatone Custom 280

One of the era’s most distinctive amp designs, Magnatones featured multi-speaker arrays and a unique “true vibrato” circuit—a potent warble heard on period recordings by such heavyweights as Bo Diddley and Buddy Holly. The 280 was further distinctive for its 6973 power tubes, two 12" speakers, and two 5" tweeters.

Photo courtesy of Dave Kyle

Ray Butts EchoSonic

Elvis sideman Scotty Moore used the tape-delay-equipped EchoSonic combo (first used by country legend Chet Atkins) on tracks such as “Mystery Train,” and, before long, rockabilly hero Carl Perkins—whose classic “Blue Suede Shoes” was later covered by Elvis, Buddy Holly, and Eddie Cochran—had also put one to use.

1960s: The British Invasion, Surf, and Garage Rock

The “flower power” decade got its nickname from spectacles such as hippies cavorting at Monterey and Woodstock with little but stems and petals in their hair. But in a much more important sense, the ’60s were the second stage of growth after musical “seeds”—and the blockbuster equipment brands—dispersed around the world during the 1950s had begun sprouting into a variety of rock movements. The Beatles’ 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show spearheaded the British Invasion, exposing millions to a revolutionary sound epitomized by first generation rock fans in “the Fab Four,” the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and the Who, as well as similar-minded U.S.-bred bands such as the Byrds. Meanwhile, reverb-soaked surf rock (popularized by the Beach Boys, Dick Dale, and the Ventures), vocal-heavy “girl groups” (including the Chantels, the Supremes, and Martha and the Vandellas), and garage rock outfits (the Standells, the Seeds, the Pleasure Seekers, and legions more) sprang up as some of the earliest offshoot movements with distinct alternative aesthetics. And of course, the end of the period saw the rise of seminal hard-rock acts like Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin.

Prime guitar movers: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, John Lennon, George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Mick Taylor, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Roger McGuinn, Dick Dale, Dave Davies, Pete Townshend, David Gilmour, John Fogerty, Neil Young.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Rickenbacker 360/12

Responsible for a huge chunk of the period’s “jangle,” the Rick 360/12 was all over the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night—which came out a few months after 73 million Americans saw them on Sullivan—which in turn inspired Roger McGuinn to apply one to tracks such as “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The Stones’ Brian Jones, the Who's Pete Townshend, and the Beach Boys' Carl Wilson were also reliant on the 360/12 during this era.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Fender Stratocaster

Leo Fender’s second solidbody had been used in a variety of contexts since its 1954 debut—including by Buddy Holly, Dick Dale, the Ventures, the Beach Boys, Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett and David Gilmour, and, in late ’69, Eric Clapton. But it was Jimi Hendrix’s genre-exploding late-’60s work on Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland, as well as a literally fiery performance at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, that exploited the limits of the innovative triple-pickup, floating-tremolo-equipped design and changed rock guitar and rock performance forever.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Vox AC30

Though its popularity has continued to grow with countless artists over the years, the glassy, compressed EL84 jangle of the AC30 will forever be synonymous with the Beatles, who had an exclusive contract with Vox early in their career. AC30s were also played by budding guitar god Jeff Beck during his Yardbirds years, the Kinks’ Dave Davies, the Stones’ Keith Richards, the Who’s Pete Townshend, and most other Invasion bands.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Fender Dual Showman

Capable of pumping 85 watts of warm grit through a set of 15" JBL D-130F speakers, the quadruple-6L6-driven Showman gave notorious volume fiend Dick Dale the decibels he wanted without having to replace his amps. It also became a go-to amp for Keith Richards during the recording of classics such as The Rolling Stones, Now! and Aftermath.

Photo courtesy of Soundgas

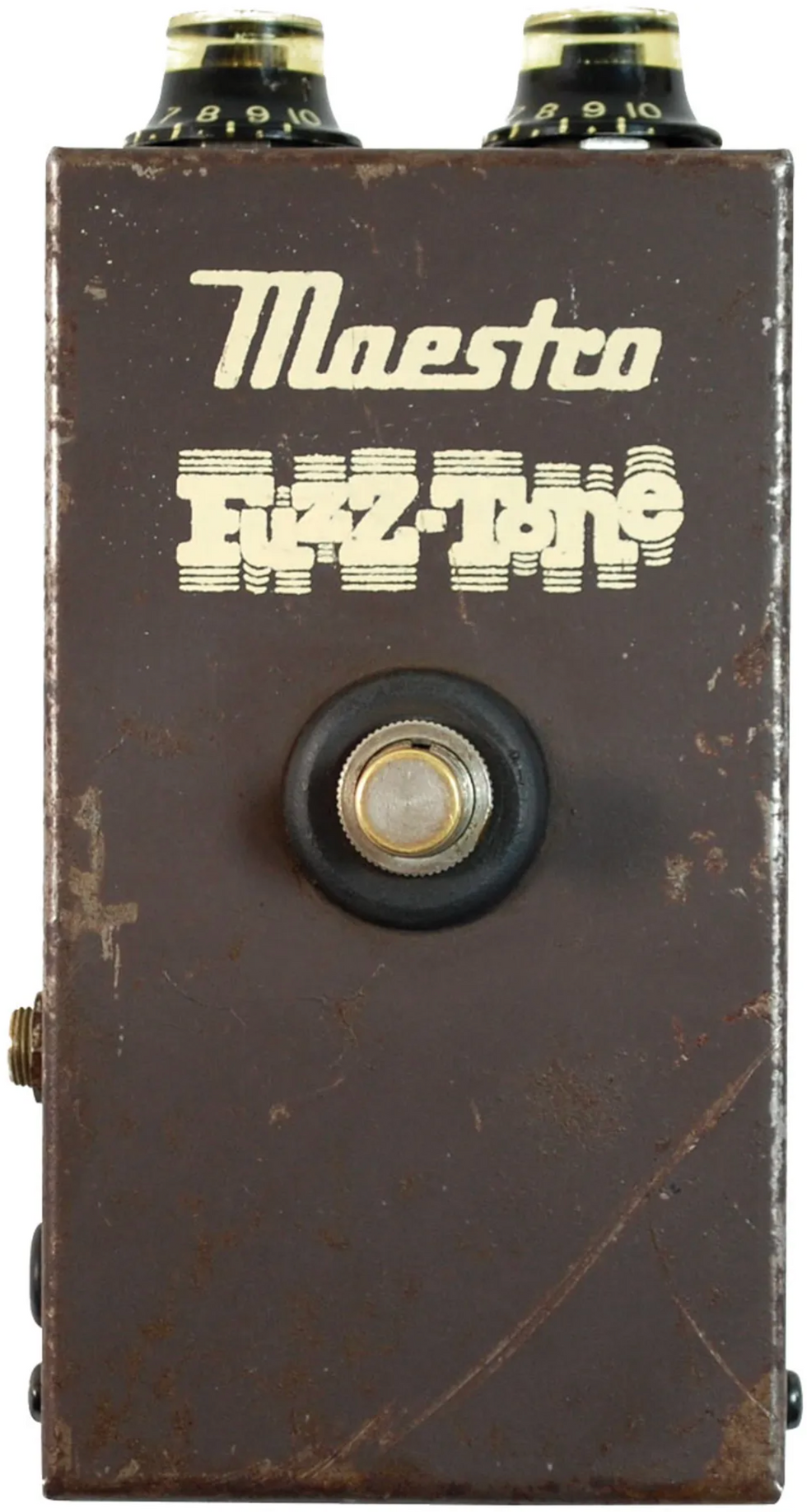

Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone

The FZ-1 wasn’t responsible for the first recording of a fuzzed-out guitar—but it was both the first commercially available fuzz pedal and the device used by Keith Richards on the first megahit to feature fuzzy riffs, the Stones’ 1965 smash “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” It was also a hit with garagers such as Lenny Kaye—guitarist for the Patti Smith Group and curator of Elektra Records’ Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968.

Sola Sound Tone Bender MKII

Jimmy Page used this three-transistor fuzz during both his late-’60s Yardbirds work and on Led Zeppelin’s explosive 1969 debut. In 1968, Pagey told Hit Parader magazine, “I get 75 percent of my sound with it. It’s very similar to a fuzz box, but I can sustain notes for several minutes if I want to.”

Photo courtesy of Soundgas

Vox wah

Developed by the Thomas Organ Company in 1966, the Vox wah was a go-to effect for Hendrix on cuts such as “Voodoo Chile,” as well as for blues-rock legend Eric Clapton on Cream’s Disraeli Gears and Wheels of Fire, and by Jimmy Page on Yardbirds tracks such as “Glimpses” (off of 1967’s Little Games).

Photo courtesy of Detlef Alder/GuitarPoint

Fender Reverb

Fender amps from the ’60s boasted gorgeous spring reverb, but for many surf gurus the tube-driven 6G15 outboard unit was vastly superior. Originally available from 1961 to 1966, it used a 12AT7 preamp tube, a 6K6 power tube, and a 12AX7 for reverb recovery, and featured three knobs—dwell, mix, and tone—that facilitated a much wider array of gonzo reverb washes.

1970s: Metal, Prog, Southern Rock & Punk

One of the more interesting aspects of gear in 1970s rock is that, although the umbrella genre grew to cover even smaller substyles in its third decade—with the birth of everything from metal (Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, Iron Maiden) to prog rock (Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Yes, Genesis, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd), Southern rock (the Allman Brothers Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd), and punk (Sex Pistols, the Ramones, the Clash)—the guitars and amps used to power such a diversity of styles were often remarkably similar. In all, the era’s music was a reflection not just of players’ increasingly creative approaches but also an impressive testament to the creativity of gear designers and the capabilities of their increasingly sophisticated technology.

Prime guitar movers: Keith Richards, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Mick Ronson, Brian May, David Gilmour, Duane Allman, Tony Iommi, Malcolm Young, Angus Young, Billy Gibbons, Nancy Wilson, Alex Lifeson, Ritchie Blackmore, Tom Verlaine, Gary Rossington, Johnny Ramone, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rory Gallagher, Peter Green, Carlos Santana, John Fogerty, Tom Johnston, Patrick Simmons, Bonnie Raitt, Neal Schon, Steve Howe, Frank Zappa, Scott Gorham, Ace Frehley, Steve Hackett, Jerry Garcia, Mike Campbell, Robin Trower, Lita Ford, Lindsey Buckingham, Edward Van Halen, Joe Strummer, East Bay Ray, Steve Jones.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Fender Telecaster

The Tele was perhaps most visibly the go-to guitar for the Stones’ Keith Richards on six monumental ’70s albums—including Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main St.—but it was also prominently used by rockabilly vet Bill Kirchen, studio legend Tommy Tedesco, David Gilmour, Robyn Hitchcock, Steve Howe of Yes, the Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde, the Clash’s Joe Strummer, the Band’s Robbie Robertson, Andy Summers of the Police, Dr. Feelgood’s Wilko Johnson, and Jimmy Page on the Zeppelin epic “Stairway to Heaven.”

Photo courtesy of Detlef Alder/GuitarPoint

Gibson Les Paul

It’s almost impossible to envision 1970s rock without the Les Paul. Seen onstage on the shoulders of everyone from Page to Beck, Duane Allman, Billy Gibbons, and the Sex Pistols’ Steve Jones, the maple-topped mahogany set-neck came into its own and provided chunk, singing sustain, and a wide variety of in-between tones via a flexible electronics array offering independent volume and tone controls for each pickup.

MXR Phase 90

Though undoubtedly used by countless players of the era, the Phase 90 gained instant fame as the most prominent effect used by Edward Van Halen on “Eruption,” “Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love,” and other tunes on his band’s game-changing 1978 debut LP.

Photo courtesy of Soundgas

Maestro Echoplex EP-3

Prior to the advent of echo pedals (such as Electro-Harmonix’s 1976 release of the Deluxe Memory Man), players such as Jimmy Page, Edward Van Halen, Andy Summers, Brian May, Tommy Bolin, Neil Young, and the Dead Kennedys’ East Bay Ray employed this cumbersome and finicky device—which used magnetic-tape cartridges and movable playback heads—to get both warm echoes and experimental “sound-on-sound” effects.

Photo courtesy of Soundgas

Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress

Developed in the mid ’70s by Mike Matthews’ Electro-Harmonix, the Mistress was the first commercially available flanger pedal, and early adopters included Robin Trower and David Gilmour, who often used it in conjunction with an Electro-Harmonix “ram’s head” Big Muff to get trademark ethereal tones on the Animals tour, on The Wall, and beyond.

Photo courtesy of Soundgas

Musitronics Mu-Tron III

Designed by Mike Beigel and released in 1972, the world’s first standalone envelope-controlled filter became a go-to tool for funk musicians, as well as for Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia on tracks such as “Estimated Prophet” and “Fire on the Mountain.”

Photo courtesy of Detlef Alder/GuitarPoint

Marshall JMP

As with the Les Paul, perhaps no image of ’70s rock pervades our collective consciousness more than that of players such as Angus and Malcolm Young, Jimmy Page, Kiss’ Ace Frehley and Paul Stanley, Maiden’s Dave Murray, Priest’s K.K. Downing and Glenn Tipton, ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, and the Allman Brothers’ Duane Allman and Dickey Betts locked in power stance in front of raging Marshall stacks. With changes such as new aluminum (rather than “plexi”) panels, slightly modified circuits, and—in some markets—a switch from EL34 to 6550 power tubes, JMP series amps such as the 1959 and 1987 brought a more aggressive bent to the famed British line.

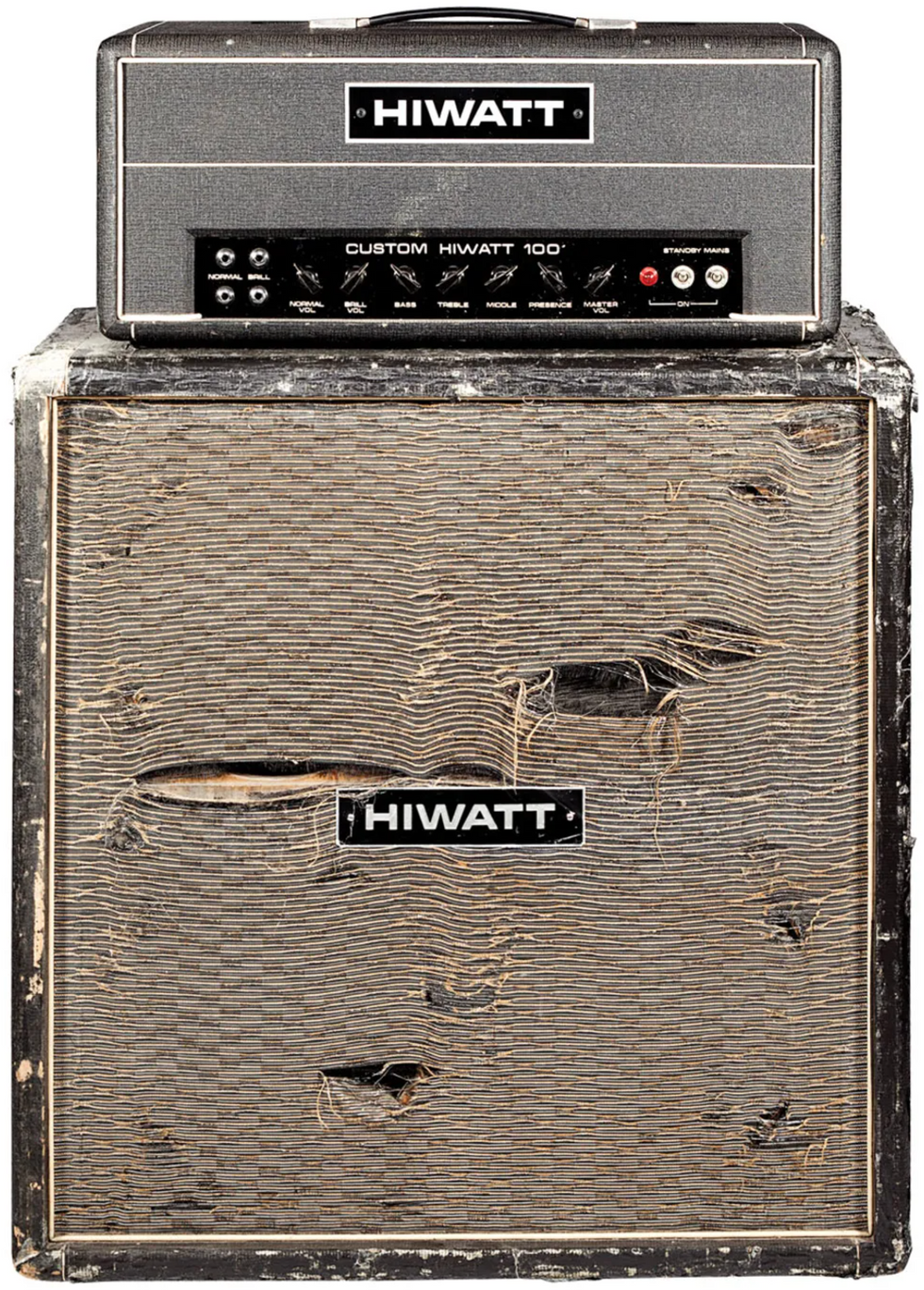

Hiwatt DR103

With explosive transients, massive headroom, and extreme roadworthiness born of meticulous, military-grade point-to-point wiring and mammoth Partridge transformers, Dave Reeves’ EL34-powered DR103 head became a favorite amp of players such as the Who’s Pete Townshend (including for the seminal 1970 Live at Leeds performances), Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour (who usually ran two DR103s through four WEM Super Starfinder 200 4x12 cabs), Jethro Tull’s Martin Barre, and future Stones guitarist Ron Wood during his years with Small Faces.

1980s: Hair Rock & New Wave

For all intents and purposes, the ’80s marked the beginning of digitalization. The same decade that brought personal computers and compact disc players into homes also saw a massive shift toward digital in music gear. Sure, many of the same guitars and amps that had ruled the ’70s stuck around or evolved, but the ’80s were when cheaper, more plentiful chip technology first enabled manufacturers to get ambitious with MIDI-controllable effectors and guitar synthesizers that put entirely new sounds, hundreds of storable presets, and deep-dive parameter tweaking within reach of everyday players. That said, toward the end of the decade, a move back toward basics was evident in the popularity of rising acts and the decline of others.

Prime guitar movers: Angus and Malcolm Young, Edward Van Halen, Gary “Dr. Know” Miller, Johnny Marr, the Edge, Andy Summers, John McGeoch, Andy Gill, Allan Holdsworth, Brian Setzer, Steve Stevens, Prince, Wendy Melvoin, Mark Mothersbaugh, Jamie West-Oram, Joan Jett, Alex Lifeson, Trevor Rabin, Neal Schon, Yngwie Malmsteen, Steve Clark, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Phil Collen, Joe Satriani, Richie Sambora, Steve Vai, John Sykes, Kirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Vernon Reid, Paul Gilbert, Kerry King, Jeff Hanneman, Dave Mustaine, Slash, Eric Johnson, Charles “Black Francis” Thompson, Joey Santiago.

Photo courtesy of Eric Ernest and Abalone Vintage

Kramer Baretta

Although 1978 was when Edward Van Halen first starting blowing minds around the world, aspiring tappers and dive-bombers put their salivary glands in overdrive when the superstar endorsed Kramer guitars in the early ’80s and the brand began selling the Baretta—a simple design whose single humbucker, single volume, Floyd Rose double-locking tremolo, and “banana” headstock mirrored the striped “Frankenstein” guitar Van Halen used live. The “super strat” concept soon drove nearly every other manufacturer to release similar designs.

Jackson Randy Rhoads Concorde V

Van Halen may have inspired both the “super strat” craze and legions of musical copycats, but Randy Rhoads—who metal legend Ozzy Osbourne chose to stand at his side as he launched his long-running solo career—was another early-’80s guitar innovator. Though he also played Les Pauls, the classically influenced Rhoads put the new company on the map when he approached Grover Jackson about producing a modern take on the V design. The asymmetrical V shape that remains popular today is based on the second Concorde prototype developed the year before Rhoads’ tragic death.

Yamaha SPX90II

With a long history as a technology innovator in multiple fields, Yamaha became a natural front-runner in the ’80s music-tech game, and their single-rackspace SPX90 effector became a huge hit in countless “refrigerator” racks of the decade. Packed with everything from high-quality reverbs and delays to parametric EQ, pitch shifting, gating, compression, and all sorts of modulation—all in a single, MIDI-controllable rack space. Famous users included Steve Vai, Edward Van Halen, the Edge, Steve Lukather, and a who’s-who of prominent players of the era.

Lexicon PCM41

Lexicon had been one of the leading names in studio-quality delays and reverberators since the early 1970s, but for guitar nuts one of the most unique, notable, and flat-out cool-sounding uses of any effector during the ’80s came courtesy of Steve Stevens, who used one of the company’s PCM41 digital delays to create the sci-fi ray gun sound at the end of his solo on Billy Idol’s runaway 1983 hit “Rebel Yell.”

TC Electronic TC 2290

One of the Reagan era’s most powerful—and prominent—rack processors was the TC 2290, released by Danish outfit TC Electronic in 1985. Occupying two rack spaces and outfitted with more front-panel buttons (44) and displays (five multi-digit LED readouts) than just about any other similar-sized unit before or since, the 2290 was famous with the same “it” crowd of the period but, perhaps most significantly, U2’s the Edge used multiple 2290s (in addition to Korg SD-3000s) to create the multitap-delay extravaganzas that became a hallmark of his style.

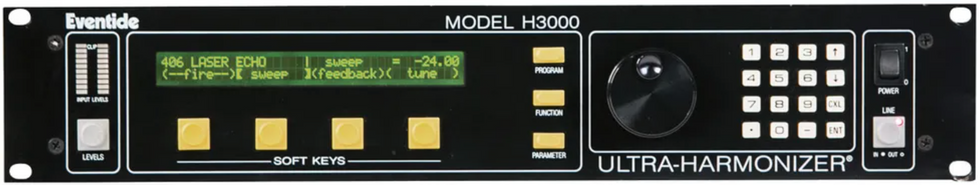

Eventide Ultra Harmonizer H3000

Whereas the ’70s saw guitar heroes using either a co-guitarist (think Allman Brothers) or multitracking (Queen’s Brian May) to create intriguing harmonized leads, the ’80s saw a significant shift (pun intended) with the 1986 debut of Eventide’s H3000. Hailed as the first intelligent, diatonic pitch-shifter, the two-space rack unit greatly expanded the creative palettes of period notables such as the Edge, Edward Van Halen, Steve Vai, and others.

Boss CE-2 Chorus

Although locking trems and hernia-inducing racks proliferated to an almost comical degree during hair-rock’s heyday, among players who either couldn’t afford the digital glut or simply preferred simpler, more streamlined rigs, Boss’ CE-2 pedal was—and still is—a stellar go-to box for creating everything from a subtle sense of motion to gloriously cheesy shimmer. Notable users included the Smiths’ Johnny Marr, Andy Summers of the Police, and Pretenders guitarist James Honeyman Scott.

Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus

The famous solid-state 2x12 debuted in the ’70s, but it rose to greatest prominence during the height of the Cold War, when players as diverse as the Cure’s Robert Smith, Billy Duffy of the Cult, Joe Satriani (on his debut LP, Not of this Earth), Andy Summers of the Police, and John McGeoch (Siouxsie and the Banshees, Magazine, Public Image Ltd) availed themselves of its ultra-clean tones and trademark analog chorus—which created a stereo effect between the combo’s two speakers.

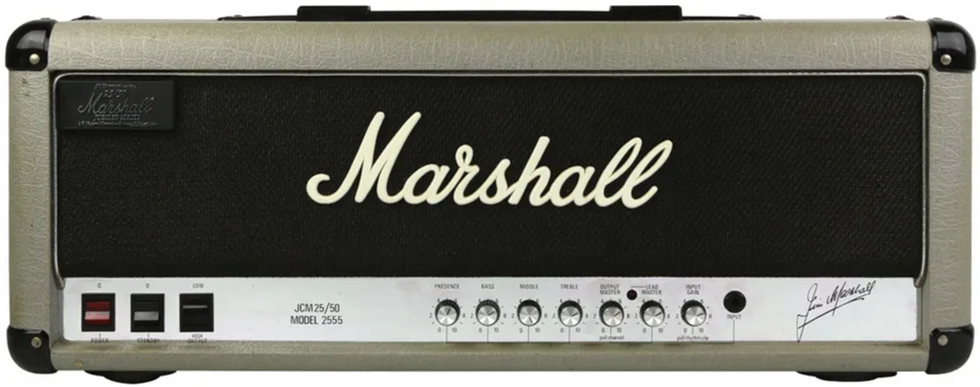

Marshall Silver Jubilee 2555

Myriad rockers and metalheads incorporated JCM800 amps in their mammoth rack-based systems during the ’80s, but the close of the decade saw a move toward simpler rigs. And while it might be simplistic to attribute the trend to a single band, it’s difficult to overstate the influence of Guns N’ Roses’ visceral classic-rock leanings on Appetite for Destruction—on which Slash, the antithesis of every other ’80s guitar hero, relied on a straightforward setup centered on Silver Jubilee heads and cabs.

1990s: Indie, Grunge, Pop Punk & Nu Metal

Between the maturation of the burgeoning alternative-rock movement from the previous decade, revulsion for ’80s hair-rock excesses, and many players’ simple reevaluation of rock tonality (as well as frantic reinvention measures taken by existing acts in an effort to remain viable), the ’90s were in many ways the opposite of the ’80s. Though not without similar bandwagon reactions. In mainstream rock, wanker-y solos and thin overprocessed preamp distortion were mostly replaced by robust, full-spectrum guitars that felt and sounded like they’d risen from the ashes of various ’60s and ’70s movements. So it’s no surprise that some of the biggest trends in gear were nods to classics of yesteryear, both in terms of harnessing actual vintage equipment and in terms of new products. Arguably, the ’90s were the true beginning of the boutique amp and pedal movements that continue strong to this day.

Prime guitar movers: J Mascis, Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo, Kim Gordon, Mark Arm, Steve Turner, Kurt Cobain, John Frusciante, Larry LaLonde, Kim Thayil, Jerry Cantrell, Stephen Malkmus, Kevin Shields, Bilinda Butcher, Boz Boorer, Mike McCready, Stone Gossard, Tom Morello, Ani DiFranco, Fredrik Thordendal, Mårten Hagström, Björn Gelotte, Dimebag Darrell, Billy Corgan, Jonny Greenwood, Ed O’Brien, James “Munky” Shaffer, Brian “Head” Welch, Eric Johnson, Carrie Brownstein, Corin Tucker, Rivers Cuomo, Brian Bell, Omar Rodríguez-López, Mark Tremonti, Mick Thomson, Jim Root, Stephen Carpenter, Adam Jones, John Petrucci, Billy Joe Armstrong, Dave Grohl, Jim Adkins, Tom DeLonge, Mike Einziger, Graham Coxon, Noel Gallagher, Bernard Butler.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop

Fender Jazzmaster

After virtually zero acceptance as a jazz guitar upon its debut in 1958 and a mere smattering of action on the ’60s surf-rock scene (plus Television’s Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd in the ’70s), the JM came into its own as the 6-string of choice for the indie- and noise-rock movement of the late ’80s and ’90s. Its unique combination of resonant chime, fuzz-friendly neck pickup, and unique vibrato system fueled influential players such as My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields and Bilinda Butcher, Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo and Thurston Moore, Dinosaur Jr.’s J Mascis, the Flaming Lips’ Steven Drozd, and Stephen Malkmus of Pavement.

Ibanez UV7

Though developed as the most affordable version of ’80s shred god Steve Vai’s signature 7-string, the UV7 found much more favor among purveyors of so-called “nu metal”—such as Korn’s James “Munky” Shaffer and Brian “Head” Welch, and Limp Bizkit’s Wes Borland—than fans of wailing, fleet-fingered leads. These acts embraced radically lowered alternate tunings and a sludgy, more metallic and experimental tonality in a blend of metal, hip-hop, and grunge aesthetics.

Boss DS-1

Though used by a wide variety of players since its 1978 debut, the very ’80s-rock tonality of the DS-1 became a rather surprising arrow in the quiver of the 1990s’ earliest and most visible—and decidedly un-’80s—guitar hero, Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain.

Electro-Harmonix Small Clone

Another of the potent tools used by Seattle grunge godfather Kurt Cobain, the one-knobbed, one-switch Small Clone provided the faux Leslie-like warble on Nirvana songs such as “Come as You Are.”

Way Huge Aqua-Puss Analog Delay

Designed in the early 1990s by Jeorge Tripps, one of the first builders on the budding boutique-pedal scene, the Aqua-Puss helped revive interest in the classic sound of analog bucket-brigade-device (BBD) effects. The scarcity of the long-discontinued chips meant the Puss was both pricey and limited to only 300 ms of delay time, but the contrast between its warm, organic sounds and the clinical sound of many ’80s delays helped fuel interest in the bygone technology, eventually culminating in resumption of BBD production—which enabled pedal makers to build more powerful delays at reasonable prices.

Electro-Harmonix/Sovtek Big Muff

Though the Big Muff had been a massive hit for Electro-Harmonix from ’69 on through the ’70s (including with David Gilmour and Frank Zappa), the focus on smoother, more straight-ahead distortion during the ’80s led to decreased mainstream popularity. Meanwhile, ’90s movers and shakers who Muff’d out included Kevin Shields, J Mascis, Mudhoney’s Mark Arm and Steve Turner, Red Hot Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante, and the Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan, while Sonic Youth's Thurston Moore preferred Russian-made Sovtek versions.

DigiTech Whammy WH-1

Countless players over the years have taken advantage of the eerily wide range of pitches availed by the Whammy pedal’s volume-pedal-like treadle, but it was political-activist-cum-riff-bomber Tom Morello who made it all his own on Rage Against the Machine cuts such as “Killing in the Name” and “Guerilla Radio.” Other 1990s Whammy-ists included the Edge, Pantera’s Dimebag Darrell, and Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour.

Matchless DC-30

Just as the boutique pedal movement really got going in the ’90s, so did the boutique amp movement, and Mark Sampson and Rick Perrotta’s Matchless Amplifiers was one of the era’s preeminent proponents. The company’s most popular offering, the DC30, aimed to replicate the chimey, class-A EL84 magic of stellar Vox specimens of yesteryear via a return to meticulously hand-wired point-to-point circuitry, custom-tailored Celestion speakers, and a 5-position cut switch. Famous users included Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready and Billy Gibbons.

Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier

Randall Smith’s innovative amps made splashes as far back as the 1970s, with the Mark I designs used by Carlos Santana, Keith Richards, and Ron Wood, as well as increasingly sophisticated channel-switching amps like the Mark II and Mark III in the 1980s. But the 1991 introduction of the Dual Rectifier quickly defined metal of the day. These 100-watters featured two footswitchable channels with independent 3-band EQs (plus presence controls) and an effects loop, but their groundbreaking namesake feature—a switch for choosing between two 5U4G tube rectifiers or a solid-state rectifier—enabled the amps to not just toggle between clean and super-saturated sounds, but to also opt for the sag and compression of traditional tube amps or a taut, chest-thumping solid-state immediacy. Early adherents included Metallica’s James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett, Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil, and countless others.

2000s: The Beginning of Everything

t’s not something we think a lot about anymore—it has become that much a part of everyday life for billions of people around the world—but the effect of YouTube, launched in 2005 and purchased by global tech juggernaut Google the following year, simply can’t be overstated. It radically altered society and culture at large. In guitardom, it revolutionized how we listen to, perceive, and learn how to play music. An entire sociological team would need considerable time and funds to evaluate the depth and significance of the impact on our tiny niche alone. But suffice to say, it blew the doors off our world, exposing players young and old to myriad new styles, faraway voices that never would have been a force in the previous era, and the chance to hear more and analyze more gear than ever before. One of the biggest net results is that it has simultaneously contributed to a more open and inclusive, yet combative and chaotic, outlook on life and music. In terms of effect on rock guitar, it’s led to a difficult-to-characterize mishmash of influences and bents—a fact that appears to be here to stay.

Prime guitar movers: Dave Grohl, Jack White, Josh Homme, Boz Boorer, Matt Bellamy, Tom DeLonge, Mark Tremonti, Zacky Vengeance, Synyster Gates, John Petrucci, Nels Cline, Bill Kelliher, Brent Hinds, Annie Clark, Fredrik Thordendal, Mårten Hagström, Björn Gelotte, Ani DiFranco, John Butler, Jonny Greenwood, Ed O’Brien, Carrie Brownstein, Corin Tucker, Mick Thomson, Jim Root, Rodrigo Sanchez, Gabriela Quintero, Dave Knudson, John 5, Ben Weinman.

Photo courtesy of William Ritter and Gruhn Guitars

PRS Custom 22

Some 30-something years after forging his own unique aesthetic into handmade guitars that combined elements of traditional Fender and Gibson axes (including a go-to scale-length halfway between the two), Paul Reed Smith’s creations finally went from being a niche luxury item for affluent blues and blues-rockers to being a totemic instrument for younger players of more adventurous bents, thanks to the growing use of models like the Custom 22 by guitarists such as Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson, Between the Buried and Me’s Dustie Waring, and Orianthi.

1960s Airline JB Hutto

At a time when high-dollar boutique pedals, amps, and guitars were all the rage, Jack White of the White Stripes single-handedly slapped a slew of players upside the head with raw tones conjured with a combination of primal playing—a mix of blues, garage, and punk—and long-forgotten gear that, until then, had pretty much been viewed as useless junk. Prices for fiberglass-bodied vintage Airline guitars, especially red 1964 JB Hutto models like the one White favored (the version shown here is a 1960), soon shot through the roof.

Fulltone OCD

Built by another early boutique pedal maker, Michael Fuller, the OCD wowed early-aughts players with the flexibility of its volume, tone, and drive setup. The secret weapon was its high-/low-gain toggle, which availed everything from Fender-y grit to Marshall-ish grind—all with stellar fidelity, low noise, and true-bypass switching.

Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler

Line 6 made a lot of noise in the ’90s with its innovative amp- and effects-modeling devices (including the POD series, and AxSys 212 and Flextone amps), but the DL4’s 15 different delay and echo types—including Echoplex, Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Memory Man, and Roland Space Echo simulations—combined with a looper and memory slots in a menu-less, 6-knob format pedal imbued it with remarkable popularity and longevity. Even amongst tech-averse, traditional-minded players. Famous users include the Edge, Minus the Bear’s Dave Knudson, Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Nick Zinner, and the National’s Aaron and Bryce Dessner.

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

One of the early boutique pedal scene’s more wild ’n’ crazy builders, Zachary Vex began making bizarre-o noise machines before it was all the rage, combining complicated, sometimes-difficult-to-control (or predict) functionality in handpainted boxes whose looks were often as off-the-wall as their sounds. The popular and long-lived Fuzz Factory was no exception: With powerful and extremely interactive gate, comp, and stab controls (in addition to volume and drive), it yields tones ranging from jagged, constipated farts to sludgy doom and squealing theremin-like mayhem. Famous users included Juliana Hatfield, Annie Clark, and Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan.

Moog MF-102 Ring Modulator

The Moog name has been synonymous with forward-thinking, experimental musical gear—including some of the industry’s most loved and sought-after analog synthesizers—for nearly 70 years now. When the company began releasing pedals toward the end of the millennium, it took guitarists a bit to grok the somewhat-daunting nature of the big beasts’ interfaces. But at the feet of adventurous-minded players such as Lee Ranaldo, Omar Rodríguez-López, and Steve Stevens they yield glorious madness.

Keeley Compressor

Oklahoma-based Robert Keeley was another early boutique pedal builder, and the stomp that originally got him noticed was his wonderfully simple but beautifully toned 2-knob compressor pedal—a modified take on a vintage Ross pedal. Debuting in 2001, it found its way into the rigs of players like Muse’s Matt Bellamy and Joey Santiago of the Pixies.

Sears Silvertone Twin Twelve 1484

White’s impact on guitardom wasn’t limited to jacking up the price of old Airline guitars. His reliance on vintage Silvertone amps for early White Stripes tunes, including the blockbuster hit “Seven Nation Army,” had a similar effect on perception of aged tube amps that weren’t Fender, Marshall, or Vox. Strange designs that looked like they’d survived some sort of Twilight Zone disaster only to be forgotten in dusty attics, basements, garages, and flea markets for years on end were hot-ticket items almost overnight. In terms of Silvertones, however, other notable users included Brendon Benson, White’s bandmate in the Raconteurs, Beck (Hansen), and Ty Segall.

Orange Tiny Terror

Cliff Cooper’s Orange Amplification had been a significant force in ’70s rock and had long been popular at the fringes of brawny British tones, but the company’s 2006 introduction of the moderately priced, 12" x 6" x 7.5", EL84-driven head—which was switchable between a very loud and bristling 15 and 7 watts—was its biggest hit in years, igniting an industry revolution that found nearly every significant manufacturer scrambling to offer a similarly small-but-potent alternative. The Tiny Terror was a hit with big names (including Gary Moore, Slipknot guitarist Jim Root, and influential producer/engineer Steve Albini) and everyday players alike.

2010s: The Explosion of Everything

Remember what we said about YouTube? For the new millennium’s second decade, take that and multiply it by a jillion. The mushrooming influence of YouTube, combined with ever-more-powerful digital devices, newer music-streaming sites, and social media like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and others, has taken the chaos of the aughts and made it the new norm, with smartphones, tablets, and new apps appearing practically by the minute to increase instant access to audio, video, and opinion around the globe. But at least the quasi normalcy of proliferating tech has offered myriad ways to create a 21st-century sense of community and drill down into specialized channels and groups that offer a measure of knowledge and experience with the sounds, gear, and players we choose to learn about. And it’s all available with an ease and speed that would have blown minds even a decade ago. We can’t turn back the clock to times when life, rock, and guitar seemed simpler, but it’s helped us more efficiently and sanely navigate the daunting entropy of it all. Another poignant effect: Pinning down trends and who uses what at any given moment is largely a futile exercise—influential players are constantly being supplied with new gadgets from manufacturers hoping they’ll post something online about it.

Prime guitar movers: Dave Grohl, Jack White, Josh Homme, Matt Bellamy, Zacky Vengeance, Synyster Gates, John Petrucci, Nels Cline, Ben Weinman, Thurston Moore, Dan Auerbach, Ty Segall, Adam Granduciel, John Dwyer, Bill Kelliher, Brent Hinds, Annie Clark, Guthrie Govan, Tosin Abasi, Javier Reyes, Misha Mansoor, Donna Grantis, Nita Strauss, Mateus Asato, Brittany Howard, Tash Sultana, Scott Holiday, John 5, Marcus King, Emily Kokal, Theresa Wayman, Phil X.

Photo courtesy of Detlef Alder and GuitarPoint

1960s Harmony H78

The interest in garage-inspired rock and vintage gear that started with Jack White has expanded in the current era, thanks to the influence of the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach, who favors a bevy of vintage amps, fuzzes, and guitars such as the Harmony H78 semi-hollowbody for his psych-blues-inflected work on hits like “Tighten Up,” “Lonely Boy,” and “Fever.”

Ibanez RGIF8

One of the most unique guitar trends of the 2010s has been the development of instruments whose multiscale construction and fanned frets are optimized for extended-range tonalities and extreme detuning. It’s an evolution in process, and Ibanez is the primary mainstream manufacturer, with accessible, production-line instruments such as the 27.2"–25.5"-scale, EMG 909X-equipped RGIF8 available at the moment. And although the interest in and popularity of these instruments seems most obviously linked to the most recent prog-shred heroes—Animals as Leaders’ Tosin Abasi and Javier Reyes, and Periphery’s Misha Mansoor—it’s important to remember these artists were immensely influenced by Swedish metal innovators Fredrik Thordendal and Mårten Hagström from Meshuggah, and Björn Gelotte of In Flames.

Strymon BlueSky Reverberator

We guitarists love our reverb. First—and for many still foremost—was the tube-driven spring variety found in classic amps. Then, a while back, Electro-Harmonix’s Holy Grail put much of that mojo in stomp form. And then Strymon showed up in 2010 with a straightforward-looking brushed-aluminum pedal that was nearly as beautiful to look at as it was to listen to. Equipped with stereo ins and outs, the ability to toggle between the current knob settings and a “favorite” preset, and a more powerful processor than other single-function digital pedals of the time, it served up gloriously ethereal plate and room reverbs in addition to a useful spring emulation. It also has a 3-position mode switch for choosing normal, modulation, and a shimmer mode—the latter of which started a whole new trend in reverberation devices. Notable users include Eric Johnson, Jeff Beck, Opeth’s Mikael Akerfeldt, and Jónsi of Sigur Rós.

J. Rockett Audio Archer

Every pedal junkie worth his or her salt knows the very polarizing story of the ridiculously expensive but incredible-sounding Klon Centaur overdrive, which came out in 1995—and which now fetches at least a couple of grand on the used market. But one of the biggest gear stories of the recent past is that pedal makers finally cracked the code, so to speak, and began offering stomps that were almost indiscernible from the real thing, and at a fraction of the price. J. Rockett Audio’s Archer was one of the first to do so.

Eventide H9

Building on decades of experience in hi-fidelity studio and stage gear, Eventide’s latest offerings have focused on putting pristine, über-tweakable reverbs, delays, modulations, and pitch-shifted presets in pedalboard-friendly packages. And while their TimeFactor, Space, PitchFactor, and ModFactor pedals have offered amazing power in moderate-sized form, the compact H9 takes much of the magic from all these pedals—plus distortions and fuzzes—and puts it in a deep-dive box the size of a trim Big Muff. Prominent users include Annie Clark, Queens of the Stone Age’s Troy Van Leeuwen, Phil X of Bon Jovi, and Aerosmith’s Brad Whitford.

Electro-Harmonix POG

For modern players looking for simple, straight-ahead, nondiatonic pitch shifting—whether for faux organ sounds or various flavors of sqwonky weirdness—there’s no need to look further than one of EHX’s POG series, which includes the Nano, Micro (shown), POG2, and Soul POG. Notable users include Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme, Mark Tremonti, and Incubus’ Mike Einziger.

EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander

Perhaps the single-greatest success story of the 2010s: EarthQuaker Devices’ Jamie Stillman is tantamount to a modern-day Mike Matthews (minus the cigar and crazy antics). After a little more than a decade in business, EQD has come out with a staggering number of pedals—everything from gnarly fuzzes that ape rare classics to spaced-out reverbs and modulators. One of the more popular items has been the Bit Commander lo-fi digitizer, which is used by players such as Deerhoof’s John Dietrich, Tera Melos’ Nick Reinhart, and Chelsea Wolfe.

Dunlop Volume (X) Mini

Dunlop’s Volume (X) Mini is noteworthy not just because of its tiny, space-saving footprint, but primarily because it also doubles as an expression-pedal—a huge boon at a time when one of the fastest-growing trends in pedal design is offering hands-free parameter control on both sophisticated multi-effectors and specialized single-function pedals.

Xotic EP Booster

As the success of the Klon Centaur proved, guitarists put a lot of stock in being able to boost their signal for a solo—or just fill out their main sound by pushing their amp a bit—without significantly altering their sound. One of the most transparent and popular bumpers of our time is the Xotic EP Booster, which both started a trend in mini boosts and became a much-relied-on stomp for players as diverse as John Butler, Ryan Adams, Graham Coxon, and Best Coast’s Bethany Cosentino.

TC Electronic Ditto

Although the concept and allure of looping extends all the way back to the ’70s Echoplex and the Boomerang Phrase Sampler of the ’90s, when TC Electronic unveiled the miniscule and incredibly simple-to-use Ditto in 2013 it took the world by absolute storm. Whereas looping had previously been of interest primarily to soundscapists, avant-garde players, and live-layering performers, the Ditto converted the masses to the benefits of being able to easily add a backing track or create an interesting distraction while tuning between songs. Famous users include Joe Perry, Maroon 5’s James Valentine, Doug Aldrich, Boz Boorer, Mateus Asato, and Andy Summers.

Fender Twin Reverb

Another of our decade’s most pervasive gear phenomena is the degree to which pedalboard sizes have grown—among both everyday players and prominent acts. With more stompbox builders in business than at any other period in history, and with many touring players resorting to backline amp rental to minimize cartage costs, the power and pristine cleans of Fender’s ’65 Twin Reverb reissue have made it a go-to “blank canvas” option for guitarists of many persuasions.

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx II

The most significant recent outboard-gear development is the incredible sophistication, fidelity, flexibility, and sonic authenticity—in both sound and feel—afforded by state-of-the-art amp- and effects-modeling rigs such as the Kemper Profiler and Fractal Audio’s Axe-Fx II. Though not cheap, these units have revolutionized studio and live playing by putting the sound of innumerable famous amps and effects at your beck and call without even requiring cabs, microphones, or pedals. Prominent users of the Axe-Fx include Rush’s Alex Lifeson, Steve Vai, Tosin Abasi, Misha Mansoor, Guthrie Govan, Metallica, the Edge, John Petrucci, Megadeth’s Dave Mustaine, and many others.

[Updated 12/9/21]