The country and bluegrass power duo show off a selection of their acoustic and electric guitars, which include gems like an original Frying Pan and a 1927 Montgomery Ward acoustic.

Since their debut, Before the Sun Goes Down, in 2014, Rob Ickes and Trey Hensley have made a name for themselves as some of the hottest country and bluegrass players in the business. As individuals, their credits range from Willie Nelson to Earl Scruggs to Merle Haggard—and as a duo, they’ve toured and recorded with artists including Tommy Emmanuel, Taj Mahal, Jorma Kaukonen & Hot Tuna, Luther Dickinson, and Molly Tuttle. It’s likely their forthcoming full-length release, Living in a Song, will only bolster their already impressive reputation.

Out on February 10th, Living in a Song is a new collection of two covers and 10 originals that were inspired by Ickes and Hensley’s life on the road. They collaborated with long-time producer Brent Maher (Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson) along with some award-winning songwriters to compose a total of 40 songs, which were then trimmed down to the resulting selection. That final cut of material leans into a classic country sound, with some Americana and bluegrass thrown in.

Along with the aforementioned credits, Ickes and Hensley have long been established, separately, as formidable musicians. Ickes has been International Bluegrass Music Association Dobro Player of the Year an incredible 15 times, and Hensley made his debut performance at the Grand Ole Opry at just 11 years old. In other words, the two have been around the block, and especially know their way around dobros and flattop acoustics.

Earlier this month, PG’s John Bohlinger met up with the duo at 3Sirens Studio in Nashville, where they played some mind-blowing music, and gave a rundown of some of their favorite guitars and gear.

Click here to pre-save Living in a Song which releases on Friday, Feb. 10.

Brought to you by D’Addario Humidipak.

Mind-Bending Bender

This dreadnought was built for Trey by the Oregon-based Preston Thompson Guitars in 2018. It’s the company’s D-MA model, with sinker mahogany back and sides and an Adirondack spruce top. But what truly makes the guitar special is its StringBender B-bender, which was built into the model by former Byrd and StringBender founder, Gene Parsons, himself. It’s also equipped with an LR Baggs Lyric. As for accessories, Trey uses D’Addario Nickel Bronze .013-.056 strings on all of his guitars, Blue Chip TAD60 picks, a Dunlop Blues Bottle slide, and a D’Addario Rich Robinson slide.

The Guts

Here's a tight shot of the inner mechanisms that engage the B-Bender.

Fighting Spirit

Trey’s favorite guitar is his 1954 Martin D-28. “I’ve had this one for about 20 years now,” he says, “I think I’m the third owner of it.” The first owner wore the neck down so that “it’s real skinny and gets super fat right at the fifth fret.” He brings his D-28 to most of his recording sessions, and while it also has an LR Baggs Lyric, “This guitar does not want to be plugged in at all,” he says, “It just fights back.” It has Brazilian rosewood back and sides; as for the top wood, “Anybody’s guess is as good as mine.”

Ugly Duckling

Found at Fanny’s House of Music in Nashville, this 1965 Harmony Sovereign Deluxe H1265 makes a bit of a statement with its prominent pickguard and mustache bridge. Or, as Trey puts it, “It’s possibly the ugliest guitar I’ve ever seen.” He calls the jumbo-bodied model his “Taj Mahal guitar,” as the bluesman requested it when Trey and Rob joined him for a few performances late last year. “I really like it,” Trey says, smiling, “It’s the guitar that shouldn’t be.”

No. 610

“This is probably one of my other favorites,” Trey says of his 2015 Wayne Henderson dreadnought—the guitar maker’s 610th build. Its specced to a Martin D-18, with mahogany back and sides. The Virginia builder famously built a few models for Eric Clapton, and notoriously has a very, very long wait list—which is why Trey was so afraid to put a pickup in it and take it out on the road after he got it. And then…. “The first night I took it out, it wasn’t on the strap button good, and it fell and hit the concrete floor. This piece here was split,” he says, gesturing to an area on the top plate. Thankfully, he was able to get it repaired. “It sounded really good before I dropped it, but it sounded about a million times better after I dropped it,” he says, “So, the moral of the story is: Drop your guitar.”

Before the War

Another D-18 copy, this 2017 Pre-War Guitars Co. model has mahogany back and sides, and is outfitted with an LR Baggs Anthem SL. It bears Taj Mahal’s signature on the front, and Trey’s on the back. The latter choice was Trey’s way of imitating Earl Scruggs, since he saw Scruggs had done the same to a couple of his instruments when he performed with him as a kid.

Black Dove

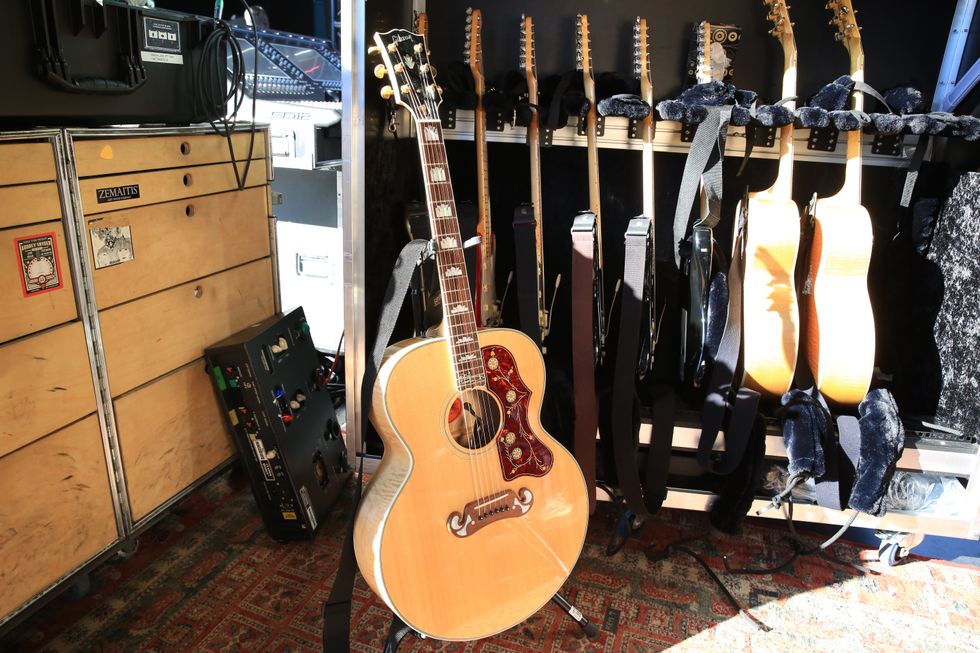

Next, a 2022 Gibson Elvis Dove, is “probably the only oddball acoustic I have,” says Trey. “I wasn’t planning on flatpicking on this thing, but I’ve already used it for some sessions.” Its maple back and sides make it the perfect choice to emulate the J-200 he borrowed from his producer for a country record he and Rob just finished recording.

Tried and True

Last in the acoustic queue is Trey’s 2021 Martin D-41. “This one’s been my main guitar for about a year now,” he says. It’s equipped with an LR Baggs Anthem SL, and has a bit of a lower setup compared to his other guitars—but with medium gauge strings, he says, it doesn’t buzz.

Loud and Clear

When Trey isn’t going DI through his LR Baggs Voiceprint, he runs his acoustics through his Fishman Loudbox Artist.

Go-To Gibson

Trey’s go-to electric is his Gibson Custom Shop 1958 Les Paul Reissue VOS, which he got in 2008. He keeps this guitar and his other electrics strung with D’Addario NYXL .010-.046 strings, which can be a bit jarring to his fretting hand when switching over from the .013s on his acoustics. “It takes a minute to not rip the neck off,” he says.

Byrd Build

This 2017 Parsons StringBender T-style was one of Gene Parsons’ early prototypes when he started building guitars.

Headshot For the Headstock

Here's Gene Parsons riding proudly on his 2017 T-style build for Trey Hensley.

To the T

The newest addition to Trey’s electric arsenal is this Berly Guitars Telecaster, built with Rocketfire ’60s-style pickups and “frets basically as big as my Les Paul.”

Trey Hensley’s Pedalboards (Acoustic)

Trey’s acoustic pedalboard is set up with a D’Addario tuner, an EHX Nano Q-Tron Envelope Filter, a Boss CE-2W Waza Craft Chorus, a Boss HM-2W Waza Craft Heavy Metal, a DigiTech Whammy Ricochet, an EarthQuaker Devices Ghost Echo Reverb, a Grace Design Alix preamp, and an LR Baggs Voiceprint. Power comes from a Voodoo Labs Pedal Power 2. It might be a bit unconventional for him to have two DIs, but he says he uses the Alix “for some EQ and mainly a boost; I’m bypassing it as a DI.” And, referring to the Voiceprint, he says, “If I can only take one pedal, it’s going to be that.”

Trey Hensley’s Pedalboards (Electric)

“I’ll preface it by saying, I don’t know what I’m doing,” admits Trey. On his electric pedalboard, he goes into his Dunlop Zakk Wylde Wah, then his D’Addario tuner—“You want that, after the wah,”—then into an EHX Micro Q-Tron, a Keeley Super Phat Mod, a Keeley Sweet Spot Johnny Hiland Super Drive, a JHS PackRat, an EHX J Mascis Ram’s Head Big Muff Pi, a Keeley Dark Side, and an MXR EVH Phase 90.

Ol’ Reliable

Trey has several amps for acoustic and electric. Today he was using a Fender ’68 Custom Princeton Reverb Reissue for his electric.

Bold and Byrly

“When you play a really good dobro, it’s in your face super fast,” says Rob Ickes, describing his main axe, a Byrl Guitars Rob Ickes Signature Series resonator—an instrument distinguished by its half-and-half ebony and curly maple fretboard. It’s equipped with a Fishman Nashville Reso Series pickup, which Ickes says is probably the first pickup that he’s used that’s nearly 100 percent faithful to the dobro sound. He uses D’Addario Nickel Bronze strings, Blue Chip thumb picks, and Bob Perry gold-plated fingerpicks, as well as a Scheerhorn bar slide.

Scheer Invention

This resonator guitar, made by Tim Scheerhorn, has Indian rosewood back and sides and a spruce top. According to Ickes, Scheerhorn “was kind of the Stradivarius of the dobro.” He was the first to start using solid woods—as opposed to the earlier use of plywood—and put sound posts inside the body, like those in a violin. “He also does a little baffle that helps force the sound out of the sound holes,” explains Ickes.

Maple Flames

The second Byrl resonator Ickes shared with us is made from flame maple, giving it that distinctive look, and is actually the first guitar he got from Byrl. He tunes it to an open G chord, which he recently discovered is the original Hawaiian tuning. It has a Beard Legend spun cone made of an aluminum alloy and named after Mike Auldridge.

One Man’s Trash

Ickes found this 1930s dobro at a music store owned by a friend outside of Franklin, Tennessee. It’s made with a stamped cone. “It’s a little bit garbage can, in a good way,” he says, “I’ll use it on sessions if I want a trashier sound.” He normally keeps it in a lower tuning, such as open D.

Family Heirloom

This 1927 Montgomery Ward guitar has a story as intriguing as its sound. It belonged to Ickes’ grandfather, who was a fiddle player: He discovered it one day in the attic of his family home. “This one spoke to me right out of the box,” he shares,” It had that funk—times 10.” It sports signatures from Taj Mahal and Merle Haggard, the latter of whom Ickes recorded a bluegrass album with back in 2006. “I take this to a lot of sessions, in case they need that funky kind of dirt-road sound,” he explains.

Let Slide

“This next one is a more modern version of that,” Ickes says of another model, a Wayne Henderson guitar which he says is the first slide guitar Henderson built. “I just said, ‘Do what you do, but raise the action a bit here at the nut.’” It has a Fishman Nashville Series Reso pickup which Ickes has go into a Fishman Aura Spectrum DI.

A Flash in the Pan

One of the most interesting guitars in Ickes’ collection is his 1932 Rickenbacker Frying Pan, an electric lap steel that was one of the first ever of its kind to be created. “It just cracks me up how they nailed it right out of the box,” he comments. Its single knob is a combination of tone and volume—“As you move to the right, it gets brighter and louder. As you move to the left it gets quieter.”

Silver Surfer

As you can tell, several of the guitars that Ickes brought on this Rig Rundown are from the 1930s, including this Rickenbacker lap steel, nicknamed the “Silver Surfer.” Its mirror-like fretboard made it difficult for Ickes to see the frets when playing live, so he had them covered in red tape, which make them stand out much better.

Black and White

The last of Ickes’ guitars is another 1930s Rickenbacker lap steel, which he fondly refers to as the “Panda,” due to its black-and-white decor. He loves how it sounds, but admits, “This is great if you don’t leave the house [with it],” as it’s very heavy and doesn’t really stay in tune.

Dulcet Dairy Tones

Despite how Ickes typically favors vintage amps, he’s fond of this newer 20-watt Milkman Creamer, which he bought with a lap steel from a friend in California after hearing the two in combination. It has all the vintage vibe without the hassle of old amps.

Small Yet Mighty

A third amp that Ickes shared with us is a vintage 1930s Rickenbacker.

Rob Ickes’ Pedalboards (Dobro)

Ickes has two separate pedal boards for his dobro and for his lap steel. Both boards are powered with separate Truetone 1 Spots. He keeps things simple on his dobro board, which includes a Fishman Aura Spectrum DI, an MXR Eddie Van Halen Phase 90, a Walrus Audio Mako Series R1 Reverb, and a ’80s era Boss DM-2 Delay.

Rob Ickes' Lap Steel Pedalboard

The simple setup trend continues with his lap steel pedalboard, which is made up of another four pedals: an EXH Micro Q-Tron, a Keeley Super Phat Mod, an MXR Phase 90, and a Keeley Omni Reverb.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)